Sep CPI & Jobless Claims Trends

Despite month/month core inflation firming, the September CPI report allows the Fed to continue cutting rates in order to not exacerbate labor market cooling.

This note reviews trends from the most notable data releases this week: the September CPI and the weekly jobless claims data reports.

September CPI: Still On Track

The topline numbers of the September CPI report came in somewhat stronger than consensus expectations. Headline CPI increased 0.2% over the month in September, similar to July and August, whereas core CPI inflation was up 0.3% m/m (three-digits: +0.312% compared to +0.281% in August).

As usual a big driver behind both the CPI inflation dynamics remained the CPI Rent of Shelter component (OER+Rent), which slowed notably in September relative to August: from +0.5% month/month to 0.2%. CPI OER inflation has been volatile across regions during the summer, with unusual strong CPI OER in the Northeast in May and weakness in June in the West. Between August and September, however, three out of the four Census regions showed a slowdown in the month/month OER inflation rate (chart above). Even so, on an annual basis there’s less clearcut evidence for the highly anticipated downtrend in the most dominant component of CPI, CPI OER. Year/year OER inflation rates remained stable well above pre-COVID levels in September in the Northeast and Midwest, whereas year/year rates in the South and West were gradually easing but also still remaining above pre-COVID trend (chart below).

To get a feel of real underlying CPI inflation, one can look at the Cleveland Fed's trimmed mean CPI measures, which cast away excess volatile elements by either taking the median (price change of the CPI component at the 50th percentile across all price changes) or a 16% trimmed mean (weighted average of price changes once both the top 8th percentile and lowest 8th percentile of price changes are deleted). The Median CPI inflation measure accelerated from +0.26% month/month to +0.34% in September, and the 16% Trimmed Mean CPI inflation measure similarly firmed over the month: +0.30% month/month vs. +0.19% in August. So, the pickup in (especially core) CPI inflation was broadly based despite the easing in housing services inflation.

Median CPI inflation is still overshooting the Fed's 2% inflation target over a six-month period, but it eased nonetheless and the six-month averaged 16% Trimmed Mean CPI inflation measure has closed in on the target (chart above).

When using the strong correlation between the CPI and PCE trimmed mean inflation series, statistical nowcasts of Median and Trimmed Mean PCE inflation (due later this month) suggest near-term underlying PCE inflation trend measures will likely have been in line with the 2% target in September (diamonds in the chart above). So the underlying dynamics continue to signal, for now, sustained inflation progress for the Fed.

Putting Initial Jobless Claims into Perspective

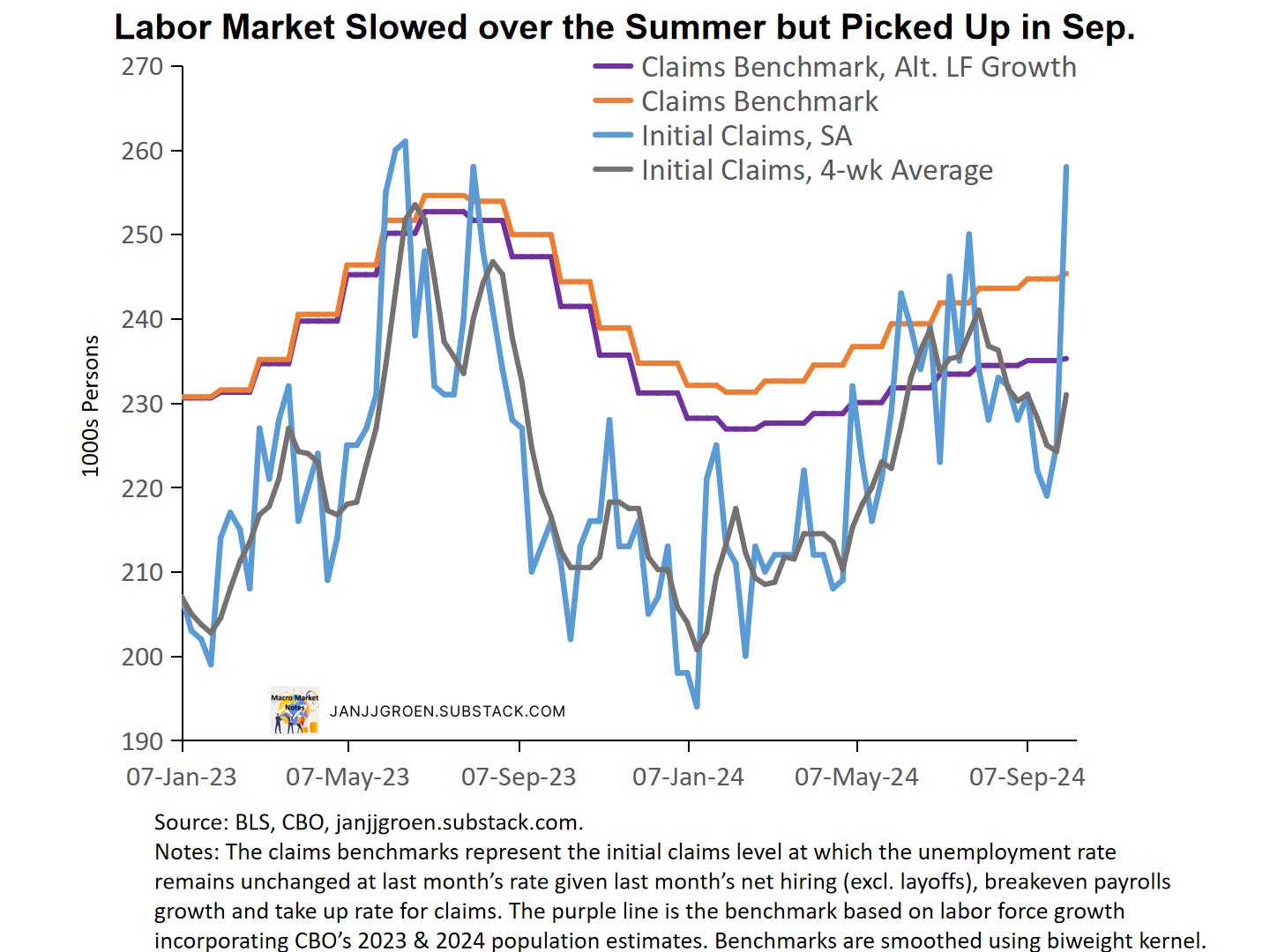

After very subdued initial jobless claims data for August and, especially, September the first initial claims data for October that came out today showed a large increase: for the week ending October 5th initial claims were 258,000 persons compared to 225,000 for the final week of September.

Dealing with seasonality in high frequency data is a complex issue, where seasonal patterns can easily shift from year to year. Nonetheless when I focus on non-seasonally adjusted data and compare today’s data with data from previous years in the same week, the spike in this week’s initial claims data remains outsized compared to previous years (chart above). In fact, initial claims over this period were the highest since 2017.

Not surprisingly, a sizeable chunk of this initial claims spike can be related to Hurricane Helene that hit six states in the Southeast towards the end of September. Of the 53,570 persons increase in non-seasonally adjusted initial claims between the week ending September 28th and the week ending October 5th, almost a third (16,241 persons) occurred in the states hardest hit by the hurricane.

Indeed, when we look at the data for two of those states, North Carolina and Florida, the two chart above confirm that initial claims increased in an outsized manner during the week after Helene hit. In case of North Carolina, the jump in initial claims is of a similar magnitude as seen after hurricane Florence hit in September 2018 (purple line in the North Carolina chart above). So, there’s a case to be made that the impact of the current outsized initial claims on the unemployment outlook mostly will be transitory in nature (although this week arrival of hurricane Milton in Florida will no doubt the above illustrated initial claims peak over the next few weeks in that state).

But outside the hurricane-stricken Southeast, other parts of the U.S. also experienced large increases in initial claims. California and Michigan combined, for example, contributed another 13,974 persons to the overall 53,570 persons acceleration in initial claims. The next two charts above suggest that in case of California the increase in claims was not necessarily unusual, at least compared to last year. However, the Michigan claims jump was really outsized. This coincided with an increased rate of layoffs at auto plants and related firms (Stellantis recently announced plans to lay off almost 2,500 persons from their Warran plant). This suggests that weather-related factors were not the only ones driving the increase in initial claims - something to keep an eye.

In terms of the unemployment outlook, initial claims are usually considered as a high frequency, real-time indicator of layoffs. What is relevant in that context is whether the layoff rate as implied by initial claims is significantly high or low to put substantial upward or downward pressure on the unemployment rate. To assess this, it is useful to determine a benchmark rate for initial claims above which initial claims will start to add to the unemployment rate.

Such an initial claims benchmark rate would be time-varying, unlike recession thresholds for claims used by many analysts, and following Braxton (2013) consists of the following three elements:

Net hiring excl. layoffs, i.e., the difference between total number hires by firms, to number of employees that quit their jobs and “other separations” (mostly retirements out of the labor force). This data comes from the JOLTS survey.

Breakeven pace of payrolls changes, which is the pace of payrolls change that would imply a constant unemployment rate. As outlined by the CEA, this breakeven pace (BE) equals 16+ year population (P) growth, the labor force participation rate (LFPR), the unemployment rate (URATE) and the ratio of establishment survey-based and household survey-based employment levels (SVYRATIO):

Take Up Rate of Claims, the ratio of average initial claims and the total number of laid off employees (from JOLTS) in a given month.

Finally, using the above three elements the claims benchmark rate can now be defined as:

where the claims benchmark for the current month equals the maximum number of initial claimants that will keep the unemployment rate constant relative to the previous month.

The chart above compares (seasonally adjusted) initial jobless claims and its four-week moving average with the claims benchmark based entirely on BLS data (orange line) as well as a claims benchmark that instead incorporates the CBO’s more aggressive population projections for 2023 and 2024 (purple line). The more aggressive population growth projections clearly have lowered the benchmark rate for claims this year (orange vs. purple lines in the chart above), where especially during the May-July period a combination of increased labor supply and slowing net hiring by firms meant that the U.S. labor market over the summer reached its limits in terms of its capacity to recycle initial jobless claimants back into new jobs.

Since August, initial claims have eased below their claims benchmark rates. And while this week’s initial claims spike probably can be deemed to be transitory, the four-week average has been creeping up as well and operates not that far below the CBO population estimate-based benchmark rate. It likely means that the labor market remains in a delicate balance around a 4.2% unemployment rate, but if jobless claims remain elevated over the coming weeks, they’ll likely approach levels that could add to the unemployment rate again.

Today’s data suggests that inflation had a bit of a setback over the month in September, but over a slightly longer horizon still has been supportive of the idea of sustained progress in bringing inflation back towards 2%, at least for now. With the labor market, also on a high frequency basis, in a delicate balance around a 4.2% unemployment rate, this means the Fed will likely continue to dial back policy restrictiveness albeit at a very modest pace in order to not derail the progress on inflation stabilization.