May Sentiment, Jobless Claims & Global Inflation Trends

May inflation surveys remain elevated. Jobless claims suggest upside unemployment risks. Higher foreign underlying inflation are less supportive for the dollar.

This post reviews recent inflation expectations trends extracted from a number firm and consumer surveys in May, recent trends in jobless claims, and, additionally, I look at recent underlying inflation trends in the euro area and Japan.

Key takeaways:

While some business and consumer surveys suggested some easing in year-ahead inflation expectations, they still remain historically elevated. Firms and households remain concerned about inflation volatility

Initial jobless claims have been ticking up recently but remain at relatively low levels. Continued claims, on the other hand, are more elevated compared to recent years. Historically low net hiring and strong population growth recently meant that relatively low initial claims do not signify a tight labor market and recent trends suggest a buildup in upside unemployment risks.

With stubborn above-target underlying inflation in the U.S. and a pickup in underlying inflation trends in the euro area and, especially, Japan, relative monetary policy differences will be a non-factor in short-term dollar moves.

May Sentiment Surveys and "Main Street" Inflation Expectations

This week's release of the May Conference Board Consumer Confidence Survey showed a cautious bounce in household sentiment, with the overall index rising from 85.7 in April to 98. This was due to improvements in outlooks across demographic groups for business conditions, the labor market, and future income. Consumers remained worried about tariff-driven inflation, but some expressed hope that trade deals might mitigate the impact. Inflation and high prices remain key concerns, but some cited lower gas prices. Year-ahead inflation expectations eased slightly, from April’s 7% to 6.5%—still historically elevated.

Inflation surveys aren't perfect but are, IMO, useful for forecasting. No measure—market- or survey-based—is flawless, so aggregation matters more than cherry-picking.

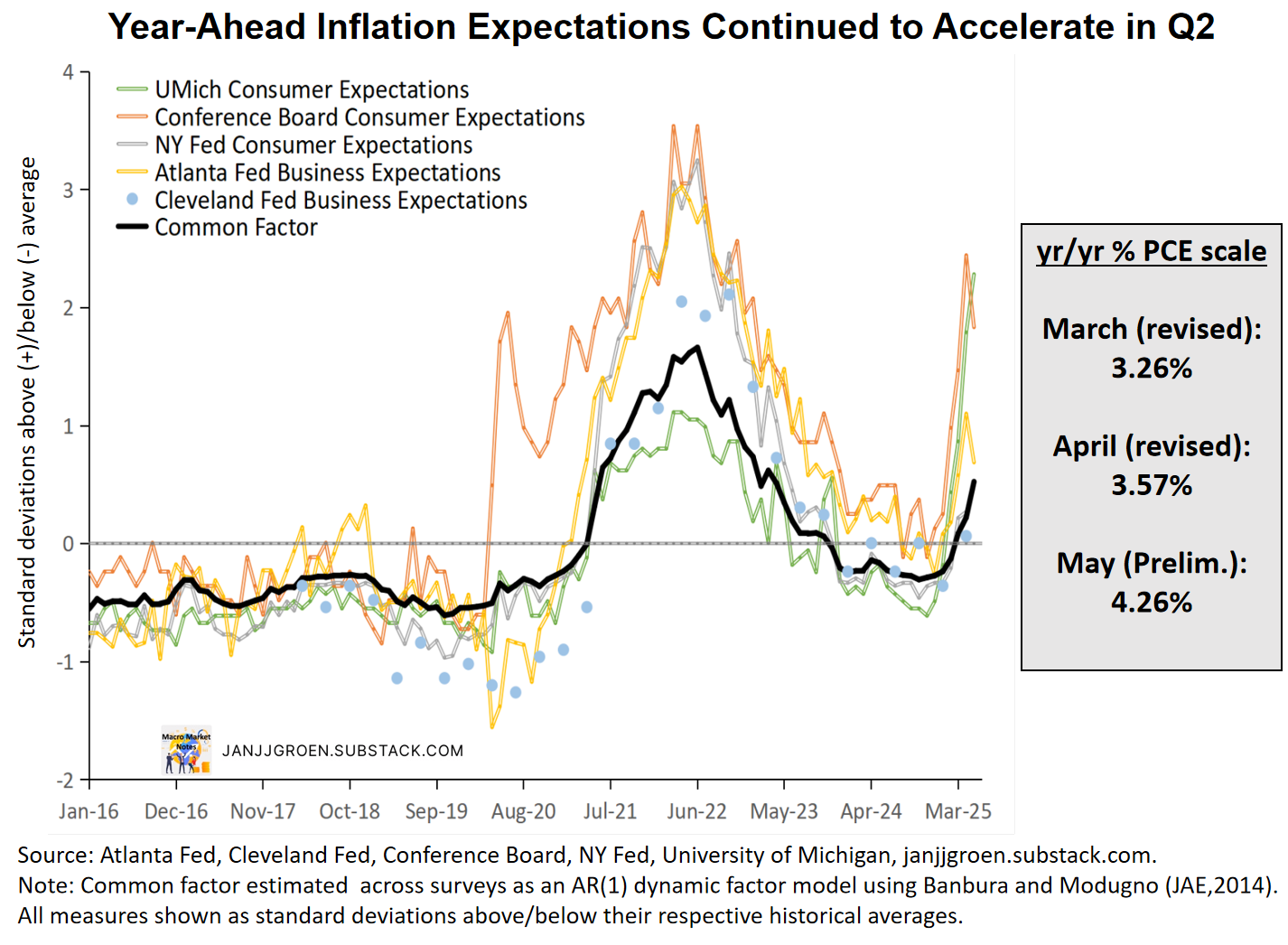

The above chart shows the common trend I extract from business and household inflation expectations, using a methodology outlined here, incorporating April data for 3 out of the surveys. This common trend indicated a sharp acceleration in expectations not only compared to Q1 but also between March and April. May data on one-year expectations has been mixed. Atlanta Fed Business Inflation Expectations and today’s Conference Board release showed some easing, with expectations still well above historical norms (see orange and yellow lines in the chart below). In contrast, the preliminary May University of Michigan survey shows rising expectations, but it didn’t yet reflect the recent paused China tariff hikes—we’ll get updated results on May 31st. Furthermore, we got April data for the NY Fed consumer survey as well as the Cleveland Fed’s Survey of Firms’ Inflation Expectations, with former unchanged over the month at 3.6% and the latter increasing from 3.2% to 3.9%.

The next chart above shows a common trend across firm and household surveys, incorporating the latest April and May data. It continues to suggest “Main Street” expectations rose notably in Q1—from 2.4% y/y PCE in Q4 to 3.3% in March and continued upward in April, but less so than estimated previously after incorporating April NY Fed and Cleveland Fed results. The recent data, as shown in the chart above, suggest 3.6% (April) and 4.3% (May) y/y PCE expectations. Firms and households continue to flag heightened near-term inflation concerns amid persistent policy uncertainty.

The preliminary May UMich 5–10-year expectations rose again, to 4.6% from 4.4% in April. The chart above shows that post-COVID long-term expectations remain structurally higher than 2016–2019, with more respondents expecting above-average inflation (orange line). Before the Great Recession (2002–2007), a similar but milder upside bias prevailed. Since 2021, this higher bias has resembled 2002–2007. But in H2 2024 and early 2025, elevated monetary, fiscal, immigration, and trade uncertainty pushed it to a February high not seen since 1979. It, however, eased slightly in March and April (UMich releases detailed percentiles with a lag). Though still elevated, a shift from boiling trade war to simmering tension might bring expectations back closer to historical norms.

While some surveys might overstate the impact of uncertainty, the broad-based elevation in expectations shows firms and households remain concerned about inflation volatility.

This Week’s Initial Jobless Claims Trends

Initial claims for the week ending May 24th increased by 14000 persons compared to the preceding week and stood at 240,000 persons.

When I focus on non-seasonally adjusted data and compare the data for the week ending May 24 with data from previous years in the same week it suggests initial claims recently have in line with the typical dynamic of this time of the year, especially compared to 2023 (chart above).

Similar (i.e. non-seasonally adjusted) data for continued claims (people who claim unemployment benefits for more than a week) scaled by the number insured workers indicate that compared to recent years, the relative number of longer unemployed people is relatively elevated (chart above). It confirms hiring and quits data from JOLTS indicating that net hiring currently is historically quite low.

In terms of the unemployment outlook, initial claims are usually considered as a high frequency, real-time indicator of layoffs. What is relevant in that context is whether the layoff rate as implied by initial claims is significantly high or low to put substantial upward or downward pressure on the unemployment rate. To assess this, I laid out earlier a methodology to determine a benchmark rate for initial claims for the current month that equals the maximum number of initial claimants that will keep the unemployment rate constant relative to the previous month. This claims benchmark number is positively correlated with net hiring (hiring minus quits and retirements) and the take up rate (initial claimants as a percentage of layoffs) and negatively correlated with the breakeven pace for payrolls growth (which depends positively on projected labor force growth) given last month’s unemployment rate. If current initial claims rise above this claims benchmark rate, initial claims could potentially start to add to the unemployment rate.

The chart above compares (seasonally adjusted) initial jobless claims and its four-week moving average with the claims benchmark rate based entirely on BLS data (purple line) as well as a claims benchmark rate that instead incorporates the CBO’s more aggressive population projections for 2020-2025 (orange line). This CBO population projection reflects the 2025 update published on January 13, which incorporates stronger net immigration estimates than the Census estimates used by the BLS, as well as a 0.9% population growth rate for 2025. The more aggressive population growth projections clearly have lowered the benchmark rate for claims since 2023 (orange vs purple lines in the above chart).

These benchmarks also incorporate the latest JOLTS data on hiring, quits and retirements, with the resulting net hirings remaining at historically low levels. Combined with the relatively high breakeven jobs growth rate based higher CBO population projections in the orange benchmark line this suggests that initial claims, and thus layoffs, have been running above replacement level in 2025 (blue & gray lines vs the orange line). So, although initial claims have been low this does not signify a tight labor market given weak hiring and strong population growth rates, and there’s upside risk building up with regards to the near-term outlook for the unemployment rate.

Global Underlying Inflation Rates in April

Both last week and this week updates for April of trimmed mean inflation measures in the euro are and Japan were published. A comparison with U.S. underlying inflation trends can be useful to assess the likely near-term trends in the relative policy stance for the Bank of Japan and ECB vs. the Fed.

The chart above contrasts year/year changes in the U.S. Median and 16% Trimmed Mean CPI with those for the euro area’s Median and 15% Trimmed Mean HICP, measured as deviations from 2% core inflation using each central bank’s preferred index. As has been apparent in recent U.S inflation reports, underlying inflation in the U.S. remains persistently above target, with a low convergence rate back to 2% PCE inflation. This is a major reason one should not expect aggressive policy rate cutting by the Fed despite the built up in upside unemployment rate risks discussed earlier — a view confirmed by the May FOMC meeting minutes published earlier this week.

In the euro area, on the other hand, underlying inflation trends have been running essentially at the ECB’s 2% HICP inflation target since early 2024. However, recently the euro area trimmed mean inflation measures have seen some acceleration in pace (blue and orange lines in the above chart). A combination of underlying inflation trend close to target, tepid economic growth and the potential of disinflation owing to U.S. tariff hikes makes likely that the ECB will more likely be cutting rates further than to stand pat. But the recent pickup in the pace of underlying inflation rates means that this potential easing in the ECB’s policy stance will be less aggressive than what was expected a month ago.

The next chart above reports on a similar U.S. — Japan comparison using the Bank of Japan (BoJ) Median and 20% Trimmed Mean CPI measures. Here we notice that while Japanese underlying inflation had been easing back to and somewhat below the Bank of Japan’s 2% CPI inflation target throughout the first half of 2024, these trends have reversed since then and recently accelerated above the BoJ’s target. So, while Japan also (like the euro area) is confronted with slower growth and the potential adverse impact of U.S. tariff increases, the underlying inflation trends means the BoJ cannot afford to steer its policy stance into more accommodative territory.

The dollar has been losing value relative to the euro and the Japanese yen this year, and this likely is part of a more medium-term trend. Persistent above-target inflation trends in the U.S. means limited scope for Fed policy rate cuts in the near-term, which could be supportive of the dollar in the short-term ceteris paribus. However, accelerating underlying inflation in the euro area and, especially, Japan means less-to-no scope for policy easing abroad and with likely Fed inaction continuing this means that relative monetary policy differences will be a non-factor in short-term dollar moves.

Thank you for this comprehensive and insightful analysis of inflation expectations, labor market dynamics, and underlying inflation trends across major economies. I appreciate how you integrated multiple survey data points with real-time labor market indicators to provide a nuanced view of both inflation outlook and employment risks. Given the persistent elevation in inflation expectations despite some easing signals, and the growing risks of upside unemployment due to the disconnect between initial jobless claims and net hiring, how do you see these trends influencing central bank communication strategies over the next 6 to 12 months?