Q2 2024 Productivity & Wages: Still Recuperating

Labor productivity remains below trend, and the labor share remains weak. Above-trend productivity growth and inflation expectations kept wage growth elevated.

Today's release of the BLS's preliminary "Productivity and Costs" report for Q2 saw a pick-up in quarter/quarter labor productivity growth after a weak Q1. As this is a very noisy, volatile series any interpretation should be done carefully. The labor share dropped on a quarterly basis after it went up in Q1. What is more relevant is the medium-term trends in these series. Additionally, these trend estimates can be used to interpret recent wage growth, such as, for example, for the Fed’s favorite wage growth gauge, the private sector wage component of the Employment Cost Index (ECI), for Q2 that was released yesterday. This note looks at the above in a bit more detail.

Key takeaways:

Over the quarter labor productivity was strong in Q2, but the labor productivity level remains below its trend estimate. Base effects resulted in a slight easing in the year/year growth rate.

The pace of trend labor productivity growth, which was 1.3% year/year in Q2, remains below an average trend labor productivity growth rate of 1.9% year/year in 2019.

The labor share declined over the quarter and fell behind its trend estimate, which is estimated to be -0.8% year/year in Q2 compared to an on average flat trend labor share estimate for 2019.

The Q2 ECI index for wages (excl. incentive pay) of private sector workers went up 4.1% year/year. This is about 1.6 percentage point above the wage growth rate consistent with 2% inflation given the trend growth rates of labor productivity and the labor share.

The Q2 overshoot in ECI wages of private sector workers was driven by above trend year/year labor productivity growth and relatively elevated near-term inflation expectations of firms and households.

Labor Productivity

Labor productivity for the non-farm business sector grew 2.3% quarter/quarter AR in Q2, after a timid 0.4% increase in Q1. On an annual basis labor productivity growth eased from 2.9% year/year to 2.7% in Q2. However, how does this compare to its underlying longer-term trend?

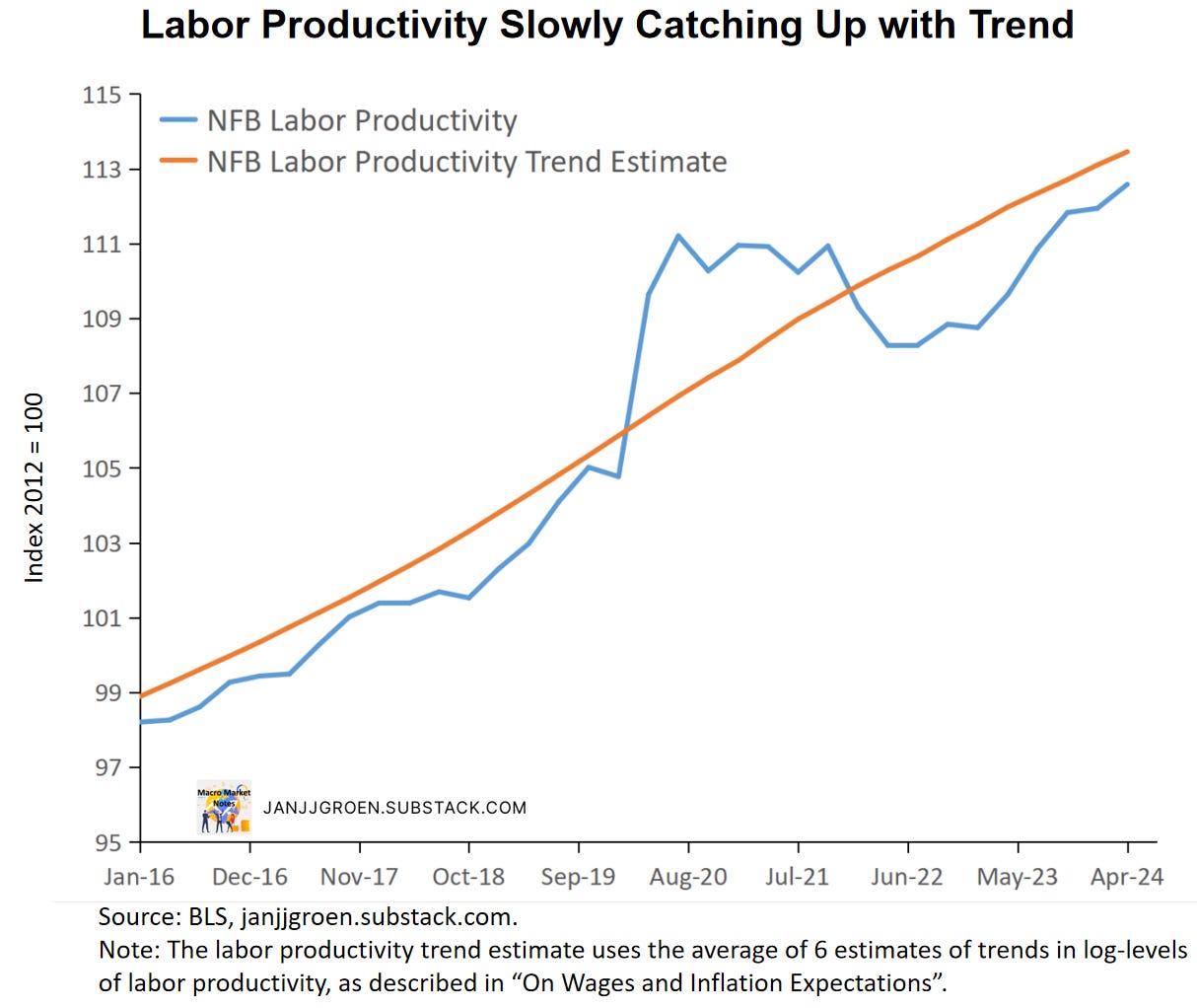

Without wanting to resort to some structural model, I base my estimate of trend productivity on a number of different purely statistical approaches as outlined here and use an average of the estimates from these approaches as the trend labor productivity estimate. As such this average reflects the uncertainty with respect to the 'true' trend level of labor productivity.

This estimate of trend labor productivity is plotted in the chart above (orange line), and it suggests a slight slowdown in trend labor productivity during and after the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. For example, trend labor productivity increased 1.3% year/year in Q2, which trails the average trend labor productivity growth rate of 1.9% year/year for 2019.

Comparing actual labor productivity with my trend estimate suggests that after a long period of declines labor productivity turned a corner in Q2 2023 and started to converge back to trend. However, the data for Q2 suggests that the pace of convergence back to trend slowed notably compared to 2023. The above-trend labor productivity growth rates in Q1 and Q2 likely reflected a continued catch-up dynamic rather than accelerated trend labor productivity growth. Given that the productivity gap relative trend is closing it is unclear whether this will continue for much longer. For now, the convergence back to trend provides a favorable impact of temporarily elevated productivity growth on prices and wages.

The Labor Share

The labor share represents the compensation firms pay their workers as a share of the firms’ revenues. This measure is useful to have alongside labor productivity data, as higher labor productivity in principle should result in higher real wages but the extent to which this happens depends on this labor share.

In Q2 the labor share for the non-farm business sector declined on a quarter/quarter basis, from +1% quarter/quarter AR to -1% in Q2. On an annual basis Q2 labor share growth was about -1.7% year/year vs. -1.2% in Q1. As was the case for labor productivity discussed earlier, I use an average across different purely statistical approaches (outlined here) to pin down the trend labor share.

The orange line in the chart above depicts the trend component of the labor share. Throughout 2016-2019 this trend labor share was stable, but it has been on a declining trajectory since 2020. For example, trend labor share growth in Q2 was about -0.8% year/year but it was on average flat throughout 2019.

Q2 Wage Growth: Interpreting the Recent ECI Moves

The Employment Cost Index (ECI) is seen as the Fed’s favorite gauge of labor compensation growth, as it corrects for any compositional shifts across sectors (much like the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker). The Q2 ECI report was published on July 31st. The most important measure from this report is the ECI for wages of private sector workers (ECIWP), stripping out non-wage labor compensation (i.e., incentive pay) as well as public sector wages. ECIWP was up 4.1% year/year in Q2, a notch slower than the 4.3% in Q1.

Much in the same way I do for monthly wage measures, one can use the trend estimates for labor productivity and the labor share outlined above to get a trend wage growth estimate consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This simply equates to 2% plus the year/year growth rates implied by the earlier discussed trend estimates of labor productivity and the labor share.

The chart above contrasts this trend wage growth measure with actual ECIWP wage growth, and it is notable that in recent years actual wage growth overshot this trend value. More specifically, for Q2 ECIWP wage growth equal to 4.1% year/year was about 1.6 percentage point above the rate of growth that would be consistent with 2% inflation.

So, what drove the recent overshooting of wage growth compared to the pace consistent with 2% inflation? To do that I decompose the gap between actual ECIWP wage growth and its 2% inflation consistent trend using the deviations of actual year/year growth relative to estimated trend growth for both labor productivity and the labor share, the gap between year-ahead inflation expectations of firms and households compared to the 2% inflation target, and an unexplained residual. The “Main Street” inflation expectations are extracted as the common trend across a number of surveys, as I described in an earlier post.

Since the previous update of the "Main Street" inflation expectations trend, I have incorporated the release of July year-ahead expectations from the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence survey from earlier this week in addition to the July releases of the University of Michigan Consumer Survey and Atlanta Fed Business Inflation Expectations Survey. The aforementioned year-ahead “Main Street” expectations eased in Q1 2024 to 2.57% in terms of year/year PCE inflation but picked up to 2.7% in Q2 2024 and 2.75% in July (chart above).

The chart above shows that, not surprisingly, during and right after the COVID lockdowns the ECI Private Sector Wages gap relative to the inflation target-based trend was heavily affected by (often offsetting) large swings in labor productivity and labor share gaps. Since mid-2021 the ECI private sector wage growth gap has been persistently positive (above a pace consistent with 2% over the medium term), as the inflation expectations gap turned positive in a sizeable way. However, throughout 2023 the impact of above-trend inflation expectations declined whereas the impact of above-trend labor productivity gained in importance.

Focusing on Q2 in the chart above, the inflation expectations gap equaled +0.7 percentage point, up from +0.57 percentage point in Q1, whereas the labor productivity growth gap contribution decreased from +1.5 percentage point to +1.4 percentage point in Q2. The labor share gap contribution flipped declined in Q1 from -0.4 percentage point to -0.9 percentage point.

So, the Q2 ECI private sector wage overshoot relative to the inflation target trend was largely driven by above trend year/year labor productivity growth and above-target near-term inflation expectations.

Note that this decomposition bears out the need to consider labor share dynamics next to that of labor productivity growth. If the labor share declines, a smaller share of business revenues flows to worker resulting on a less than proportional increase in real wages when productivity grows faster. Indeed, most of the above-trend productivity growth in Q2 got absorbed by a contraction of the labor share below its trend pace. And given the declining trend in the labor share, this also explains why the current inflation target pace of wage growth is below the corresponding levels in the pre-COVID years.

Beyond Q2, “Main Street” inflation expectations as of July suggest that the inflation expectations gap could contribute somewhat more to ECI private wage growth in Q3 than in Q2. Also, given that the gap between the current and trend levels of labor productivity is closing year/year labor productivity growth beyond Q2 could slow down. Thus, going into 2024 Q3, we could have more easing in the ECI wage growth for private sector workers, but inflation expectations of firms and household likely will keep it above inflation target-consistent pace.