Wages and Inflation Expectations - April 2024 Update

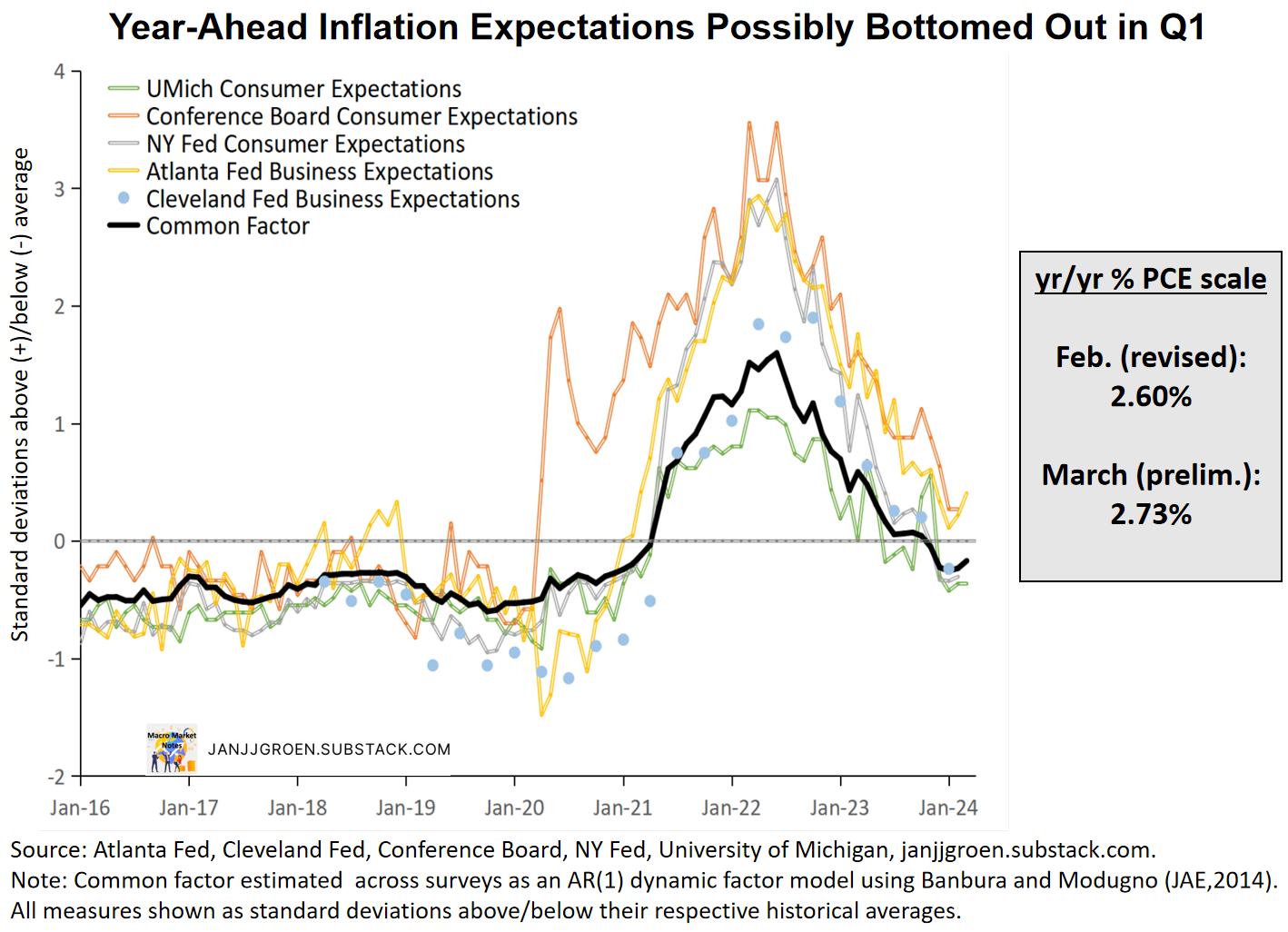

Wage growth outpaced the inflation target-consistent pace. Inflation expectations stabilized in Q1 at 2.6% (PCE inflation terms) and went up slightly in April.

Another month, another update of my wage growth framework. This framework can be used to interpret wage growth trends relative to inflation expectations and the Fed’s inflation target. The resulting W* measure reflects a trend wage growth rate where demand and supply in the labor market are in balance given an inflation outlook. It is equal to either the 2% inflation target or year-ahead inflation expectations plus a trend labor productivity growth estimate as well as a trend labor share growth estimate. The latter component corrects my original W* for long-run shifts in workers’ compensation as a share of non-farm business sector revenues (a.k.a. the labor share).

With new wage data for March, revised labor productivity and labor share data for Q4 and updates of inflation expectations data for March and April, this note will update the above-mentioned wage growth framework.

Key takeaways:

Since November “Main Street” inflation expectations eased towards a 2.6% PCE equivalent rate in 2024 Q1. In April the preliminary estimate ticked up slightly to close to 2.7%.

Trend wage growth based on these inflation expectations (W*) slowed during Q1 and increased somewhat recently, which suggests potential additional wage disinflation for 2024 leveled off.

With W* consistent with about 2.6% PCE inflation, this wage growth trend measure has closed in on the Fed’s 2% inflation target compared to a year ago. But any actual wage growth easing in line with this measure will still keep wage growth at an above-target pace.

Actual wage growth measures for March did slow but remain higher than the inflation target-consistent pace. Corrected for expected inflation, trend productivity growth and trend labor share growth, wage growth continues to support households’ real incomes and spending, both in Q1 and going into Q2.

Inflation Expectations

One of the W* trend wage growth measure I publish builds on inflation expectations surveys drawn from “Main Street”, i.e., five inflation expectations samples from households and firms. Following my original W* note, I extract a common signal from these inflation survey measures by means of a single dynamic common factor that depends on its own lag using the approach of Banbura and Modugno (JAE, 2014).

I have plotted in the chart above the available individual expectations series I used for my March update on wages and inflation expectations. Alongside them I depicted the corresponding common factor estimated across these series, as well as the scaling of this factor in year-on-year PCE inflation terms. In March the common trend across these surveys suggested that “Main Street” inflation expectations had been stuck around 3.2% between July and October but then declined to around 2.6% in December, January and February, with signs of an uptick to about 2.7% in March.

Since the March update, four out of the five underlying surveys got updated, two with observations for February and two surveys providing expectations for March:

The March 26th Conference Board U.S. Consumer Confidence survey for March pointing to a modest increase in the mean 12-month ahead inflation expectations from 5.2% to 5.3% in March.

The April 8th NY Fed March Survey of Consumer Expectations, which indicated an unchanged median year-ahead expectation at around 3% for the third consecutive month.

The April 12th preliminary University of Michigan survey for April, which showed median year-ahead inflation expectations went up from 2.9% in March to 3.1%.

The April 17th Atlanta Fed Survey of Business Inflation Expectations showing a slight decrease in the 12-month ahead mean inflation expectations from 2.4% to 2.3% in April.

The re-estimation of the common factor across “Main Street” inflation expectations using the updated surveys is shown in the chart above and suggests a downward revision to February inflation expectations from previously 2.73% in PCE terms to currently 2.57%. However, the preliminary estimate for April shows a modest uptick from the preceding month to 2.67%. After the decline in near-term inflation expectations at the end of 2023 these inflation expectations hit a floor at around 2.6% in Q1 2024 with very tentative signs of a recent rise in expectations.

Trend Labor Productivity and Labor Share Growth Rates

Since the release of the initial labor productivity and cost Q4 2023 data the BLS published on March 8th revisions to its Q4 estimates of these data. Overall, these revisions (which included annual benchmark revisions that potentially impacted 2018-2023 data) did not change the outlook for labor productivity and the labor share much. On a year/year basis Q4 2023 labor productivity growth was revised down slightly from 2.7% to 2.6%. Nonetheless, despite these revisions, my estimate of the year/year trend labor productivity growth rate for Q4 remains unchanged at around 1.3% year/year, as is shown in the chart below, which is subdued historically.

The labor share equals the ratio of total workers compensation relative to nominal output of businesses. The aforementioned data revisions led to a slight upgrade in the year'/year labor share growth for Q4 2023 from initially flat to +0.1%.

As for labor productivity, I approximate the labor share trend by taking the average of six trend estimation methods applied to the actual labor share data, using the methodology outlined in my original W* note. The chart above shows this labor share trend estimate, which continues to show a drift down, although the revisions meant for an ever so slightly less pronounced decline. Nonetheless, the wage growth level consistent with the Fed’s inflation target is likely lower than usually assumed in the policy debate given the decline in trend labor share on top of subdued trend labor productivity.

Wage Growth

To recap, to assess wage growth trends I combine the following three elements I discussed in the previous sections, i.e.,

The trend productivity growth estimate described earlier (assuming a Q1 trend labor productivity level equal to the trend labor productivity change for the preceding quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

A similar estimate of trend labor share growth (assuming a Q1 share level based on the trend labor share estimate for the previous quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

And, either the year-ahead inflation expectation proxy based on the common factor from firm and household surveys or the 2% inflation target.

The sum of 1-3 above will result in two alternative trend wage (W*) measures, and I compare these below with measures of average hourly wages of workers that are robust to compositional changes over the month.

Wage data from the monthly BLS jobs report are notoriously noisy, given that they are revised often and do not correct for the sectoral and skills composition of jobs growth over the month. There are better quality wage data available, such as the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker, but the Atlanta Fed does construct a rudimentary composition correction for average hourly earnings from the jobs report, which can be found here. I use both sources to assess wage developments.

The chart above shows that both wage growth measures from the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker where stable at around 5.2% year/year throughout September-December, then eased to around 5% in January and February, followed by more easing towards 4.7%-4.9%. Similarly, the smoothed year/year growth of the composition adjusted AHE hovered around 4.5% in September-December and then slowed to about 4.2% in March. (purple compound line in the chart above). These wage growth measures have been consistently overshooting the expectations-based W* metric since Q1 2023, suggesting we had continued positive expected real wage growth over the past year or so.

Compared to the previous update, the year-ahead expectations W* metric remained broadly increased slightly in April compared to March (blue line in above chart), in line with the earlier discussed dynamic seen in “Main Street” inflation expectations in Q1 and April. More medium-term takeaways remain in line with what I reported over the last couple of months:

Actual wage growth rates remain stubbornly above both the expectations-based (currently in line with about 2.6% PCE inflation) and inflation target-consistent W* levels.

With the declining trend in the labor share incorporated into the W* measure, the Fed needs to see year/year wage growth of about 2.6% for it to be consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium term.

Implications

The data on “Main Street” inflation expectations do suggest that expectations eased notably since November after remaining stuck for the prior four months. However, more recent inflation expectations data do show that “Main Street” inflation expectations have reached a floor in Q1 and might be creeping up again. Consequently, recent inflation expectations dynamics suggests that the expected degree of wage growth easing for the remainder of the year seems to, at least, have leveled off.

Wage contracts typically are staggered across sectors and across the year. In addition, the catch-up dynamic driving above-trend labor productivity growth have also temporarily kept wage growth north of the inflation target-consistent pace. But if my inflation expectations estimate remains contained and labor productivity growth slows towards trend, we should see throughout 2024 a convergence of actual wage growth metrics towards the blue line in the chart above.

But a relatively strong labor market drove the positive expected real wage growth rate seen since Q1 2023 and this has been a boost for expected real wage incomes of households. The resulting robust levels of consumption spending could arrest any further disinflation of, in particular, service prices, which then could result in higher “Main Street” inflation expectations. As a consequence, wage growth in that scenario would top out at a rate above the inflation target-consistent rate, reinforcing the “stickiness” of services inflation. Indeed, with spot inflation data showing signs of some firming over the past three-to-four months this scenario has become a more plausible possibility.

The Fed will be patient in waiting for signs of such a gradual convergence of wage growth towards inflation expectations-consistent rates and rate cuts will not be on the Fed’s radar for a while.