Q4 Productivity & Wages: The Catch Up Continues

Labor productivity is catching up with trend and the labor share remains weak. Productivity and expected inflation kept wage growth above inflation target pace.

Today's release of the BLS's preliminary "Productivity and Costs" report for Q4 suggests another quarter of strong labor productivity growth. As this is a very noisy, volatile series any interpretation should be done carefully. Similarly, the labor share was essentially flat over the quarter. What is more relevant is the medium-term trends in these series. Additionally, these trend estimates can be used to interpret recent wage growth, such as, for example, for the Fed’s favorite wage growth gauge the Employment Cost Index (ECI) for Q4 that was released yesterday. This note looks at the above in a bit more detail.

Key takeaways:

Labor productivity growth was again strong in Q4, but labor productivity still undershoots its trend estimate.

The pace of trend labor productivity growth slowed down during and after the pandemic, which read 1.3% year/year in Q4 compared to an average trend labor productivity growth rate of 1.9% year/year in 2019.

The labor share remained flat and below its trend estimate, which declined by 0.7% year/year in Q4 compared to an on average flat trend labor share estimate for 2019.

The Q4 ECI index for wages of private sector workers went up 4.3% year/year in Q3. This is about 1.6 percentage point above the wage growth rate consistent with 2% inflation given the trend growth rates of labor productivity and the labor share.

The Q4 overshoot in ECI wages of private sector workers was driven by elevated near-term inflation expectations of firms and households and above trend labor productivity growth.

Labor Productivity

Labor productivity for the non-farm business sector grew 2.7% year/year in Q4, after increasing 2.3% in Q3. This is quite a turnaround in labor productivity growth compared to the seven quarters that preceded Q2 when labor productivity dropped throughout most of that period. However, how does this compare to its underlying longer-term trend?

Without wanting to resort to some structural model, I base my estimate of trend productivity on a number of different purely statistical approaches as outlined here and use an average of the estimates from these approaches as the trend labor productivity estimate. As such this average reflects the uncertainty with respect to the 'true' trend level of labor productivity.

This estimate of trend labor productivity is plotted in the chart above (orange line), and it suggests a slight slowdown in trend labor productivity during and after the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. For example, trend labor productivity increased 1.3% year/year in Q4, respectively, which trails the average trend labor productivity growth rate of 1.9% year/year for 2019.

Comparing actual labor productivity with my trend estimate suggests that after a long period of declines labor productivity turned a corner in 2023 and started to converge back to trend. Thus, the above-trend labor productivity growth rates in Q3 and Q4 likely reflects a catch-up dynamic rather than accelerated trend labor productivity growth. As in the chart above Q4 labor productivity has converged closer to trend, we should expect possibly another above-trend growth rate for 2024 Q1 after which labor productivity growth likely will slow in line with trend growth.

The Labor Share

The labor share represents the compensation firms pay their workers as a share of the firms’ revenues. This measure is useful to have alongside labor productivity data, as higher labor productivity in principle should result in higher real wages but the extent to which this happens depends on this labor share.

In Q4 the labor share for the non-farm business sector was essentially flat on a year/year basis, after it declined year/year for nine of the eleven preceding quarters. As was the case for labor productivity discussed earlier, I use an average across different purely statistical approaches (outlined here) to pin down the trend labor share.

The orange line in the chart above depicts the trend component of the labor share. Throughout 2016-2019 this trend labor share was stable, but it has been on a declining trajectory since 2020. For example, trend labor share growth in Q4 was -0.7% year/year but it was on average flat throughout 2019.

Q4 Wage Growth: Interpreting the Recent ECI Moves

The Employment Cost Index (ECI) is seen as the Fed’s favorite gauge of labor compensation growth, as it corrects for any compositional shifts across sectors (much like the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker). Yesterday, the Q4 ECI report was published. The most important measure from this report is the ECI for wages of private sector workers (ECIWP), stripping out non-wage labor compensation as well as public sector wages. ECIWP was up 4.3% year/year in Q4, somewhat down from 4.5% in Q3.

Much in the same way I do for monthly wage measures, one can use the trend estimates for labor productivity and the labor share outlined above to get a trend wage growth estimate consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This simply equates to 2% plus the year/year growth rates implied by the earlier discussed trend estimates of labor productivity and the labor share.

The chart above contrasts this trend wage growth measure with actual ECIWP wage growth, and it is notable that in recent years actual wage growth overshot this trend value. More specifically, for Q4 ECIWP wage growth equal to 4.3% was about 1.6 percentage point above the rate of growth that would be consistent with 2% inflation, only slightly less than wage growth overshoot of around 1.7 percentage point in both Q2 and Q3.

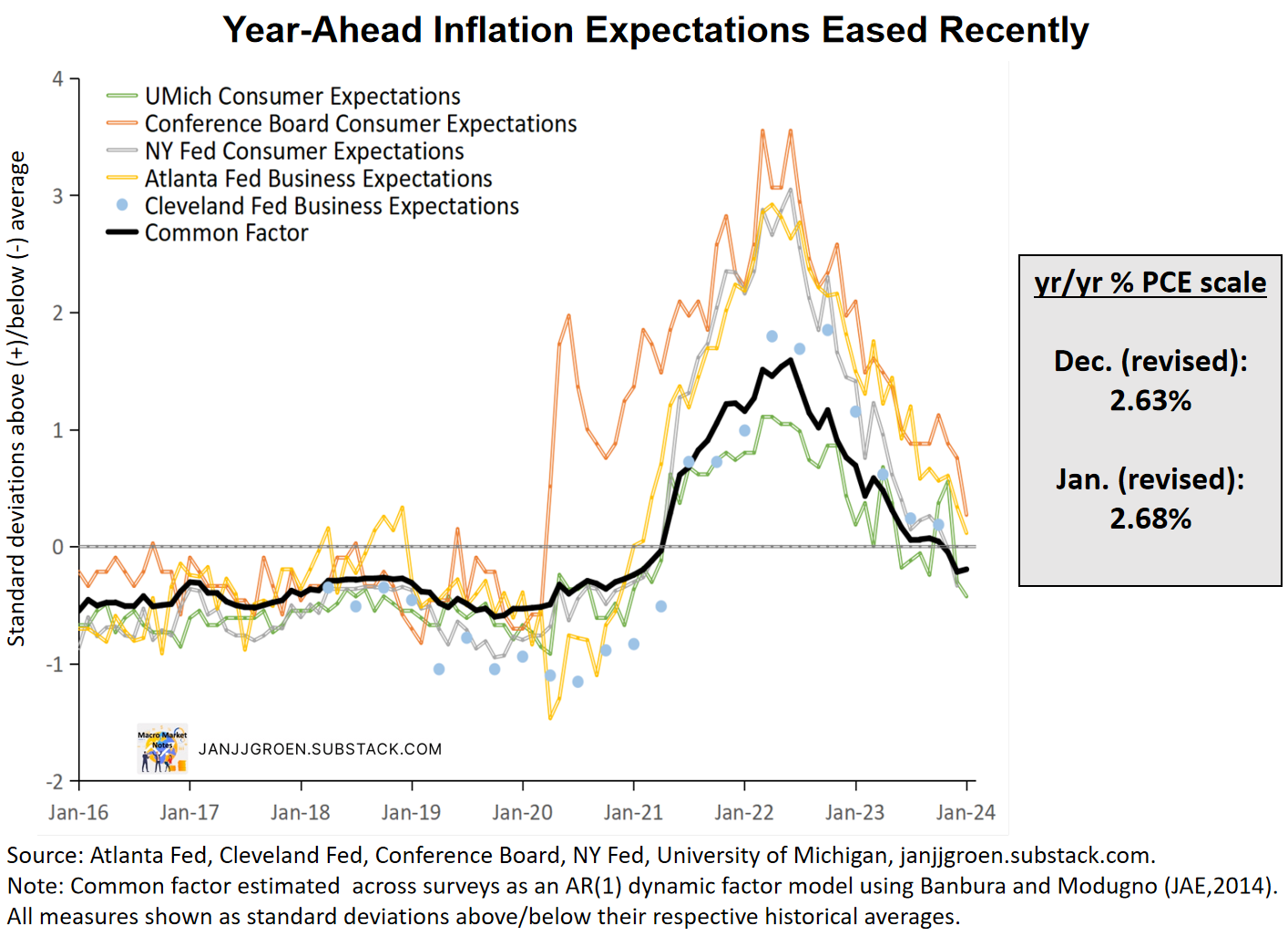

So, what drove the recent overshooting of wage growth compared to the pace consistent with 2% inflation? To do that I decompose the gap between actual ECIWP wage growth and its 2% inflation consistent trend using the deviations of actual growth relative to estimated trend growth for both labor productivity and the labor share, the gap between year-ahead inflation expectations of firms and household compared to the 2% inflation target, and an unexplained residual. The “Main Street” inflation expectations are extracted from a number of surveys, as I described in an earlier post.

As discussed in my post-January FOMC meeting note, I have incorporated the release of January year-ahead expectations from the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence survey from earlier this week in this inflation expectations aggregate. The aforementioned year-ahead “Main Street” expectations were stuck around 3.2% in terms of year/year PCE inflation for July-October but resumed its decline in November to 3% and further down to 2.7% in January (chart above).

The chart above shows that, not surprisingly, during and right after the COVID lockdowns the ECIWP gap relative to the inflation target-based trend was heavily affected by (often offsetting) large swings in labor productivity and labor share gaps. Since mid-2021 the ECIWP wage growth gap has been persistently positive (above a pace consistent with 2% over the medium term), as the inflation expectations gap turned positive in a sizeable way.

Focusing on Q4, the inflation expectations gap equaled +0.9 percentage point a decline from +1.2 percentage point in Q3, whereas the labor productivity growth gap contribution increased from +0.8 percentage point to +1.4 percentage point in Q4. The labor share gap contribution flipped from -0.6 percentage point in Q3 to +0.7 percentage point. So, the Q4 ECI wage overshoot relative to the inflation target trend was largely driven by above-target near-term inflation expectations and even more so by above trend labor productivity growth.

Beyond Q4 “Main Street” inflation expectations as of January suggest that the inflation expectations gap could contribute less to ECI private wage growth in 2024 Q1 than in 2023 Q4. Also, labor productivity growth beyond the next quarter is most likely to slow down again as labor productivity approaches its trend value. Thus, going into 2024 Q1 and beyond, we could have more easing in the ECI wage growth index for private sector workers as inflation expectations of firms and household and labor productivity growth move closer to their longer-term trend values. This would be good news for the Fed once it likely starts cutting policy rates by mid-2024.