Jan FOMC Meeting: Prepping for Rate Cuts

As the FOMC started discussing the timing of rate cuts, with stable expected real rates and solid economic growth these will likely not happen before mid-2024.

Another FOMC meeting another decision of no change in the Fed funds rate target range. With the today’s policy statement getting rid of explicit mention of rate hikes (“The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals.”), Chair Powell’s remarks today made clear that the FOMC in earnest started to discuss the timing of rate cuts. The Chair, however, made clear that the Fed will take its time and use its Q1 deliberations to how assess how temporary the disinflation seen over the past six months has been given the strong performance of the real economic activity over that same period.

Key takeaways:

The FOMC decided to keep the Fed funds target rate unchanged at 5.25%-5.50%, and no longer signaled policy rate hiking bias going forward.

Underlying core services inflation and near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations have shown further signs of downward momentum.

But the labor market and consumption spending remain relatively strong.

Since the September FOMC meeting, expected near-term real interest rates have peaked and eased somewhat, with the perceived policy stance just a notch below the Fed’s own assessment of its stance.

As the expected year-ahead real rate path remains contained and real economic activity levels remain strong, the FOMC will likely be patient in assessing more progress in both spot inflation and inflation expectations data as well as labor market trends before deciding to cut policy rates.

My modal view is for Fed funds rate cuts likely not to start until mid-2024. There is, however, a risk cuts could commence in March owing to a combination of the Fed overestimating the restrictiveness of its current policy rate level and continued rapid disinflation pace in the spot inflation data over the next few months.

The Fed’s Conundrum: Disinflation and Strong Real Economic Activity

With core goods price disinflation due to normalizing supply side constraints and external factors, and housing services inflation is expected to ease given weak new rents, the Fed has focused for a while on developments in core services excl. housing inflation. The latter component of core inflation is mainly driven by:

Labor costs, as most of the categories in core services excl. housing inflation are labor-intensive in nature.

Consumption expenditures, as the bulk of U.S. consumption spending is traditionally geared towards services spending.

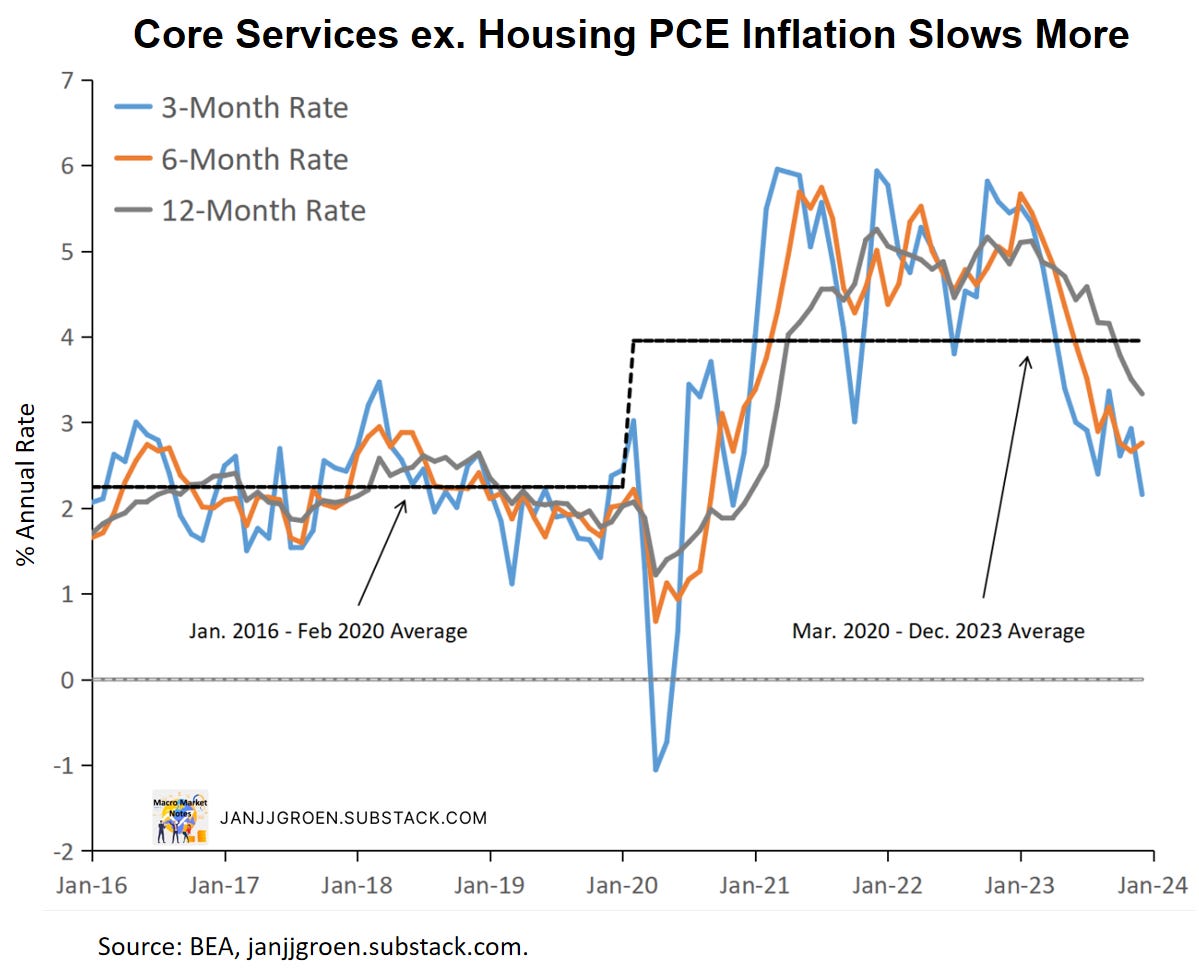

While momentum in PCE core services excl. housing inflation has been sticky around a 4% m/m annual rate for most of the time since 2021, since the October Personal Income & Outlays report we have observed signs that this inflation measure could finally break south of this 4% level (chart above).

Another key factor in the Fed’s assessment of progress on inflation normalization are near-term inflation expectations of firms and households, as affects wage negotiations, price setting and spending. Research has shown that these types of inflation expectations are the stickiest and often are positively correlated with growth expectations of these same firms and households. Since July I have been monitoring the common trend across near-term inflation expectations from surveys of firms and household from different sources, in order to aggregate these different measures and simultaneously filtering out idiosyncrasies from the individual surveys.

After updating the previous estimate of this common trend across firms’ and households’ inflation expectations with the January release of the Conference Board Consumer Confidence survey, we note from the chart above that:

After sharply declining in 2023 H1, the common trend across near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations stabilized in July-October around a year/year PCE inflation equivalent rate of 3.2%.

Since November, near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations commenced easing again, to 3% in November and then further down to about a 2.7% year/year PCE inflation equivalent rate in January.

When taking together the recent trends in non-housing core services inflation and near-term inflation expectations on board these new data points, these are encouraging signs for the Fed that underlying inflation trends might have started to reset on a disinflationary path back towards 2%. Note, however, that this turnaround has been a fairly recent phenomenon, and the Fed needs to see more continued progress as technical issues (i.e. the forthcoming CPI seasonal adjustment reset) as well as continued real activity strength continue to muddle the inflation picture.

In terms of real activity, the economy has been doing really well mainly owing to strong consumption spending, with underlying consumption growth suggesting that will continue into at least 2024 Q1 (chart above). Despite rising credit costs, households were able to keep spending at a healthy rate supported by a still big pile of excess savings and growing income out of wages.

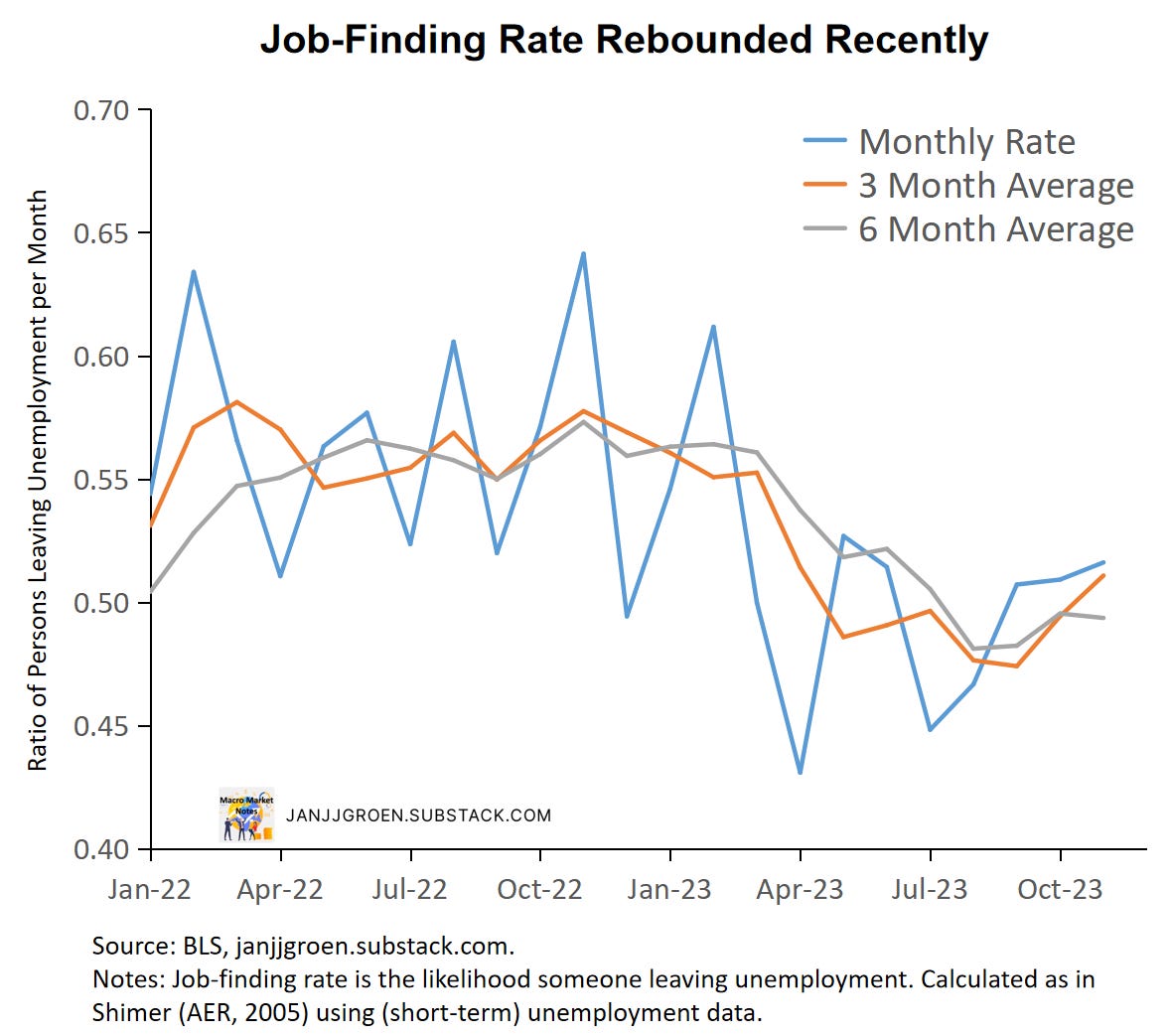

Additionally, the labor market remained solid, which has been an important source of continued elevated consumption spending. In December payrolls growth momentum remains firm and wage growth firmed and outpaced the medium-run rate that is consistent with 2% inflation. And in a sign that labor demand might be recovering after slowing earlier in 2023, the job-finding rate has been trending upwards since the fall (chart above). Thus, over the next few months the Fed needs to make sense of two diverging trends: possibly persistent disinflation of core services prices versus continued consumer and labor market strength.

Real Rates are Key for Rate Cutting Prospects

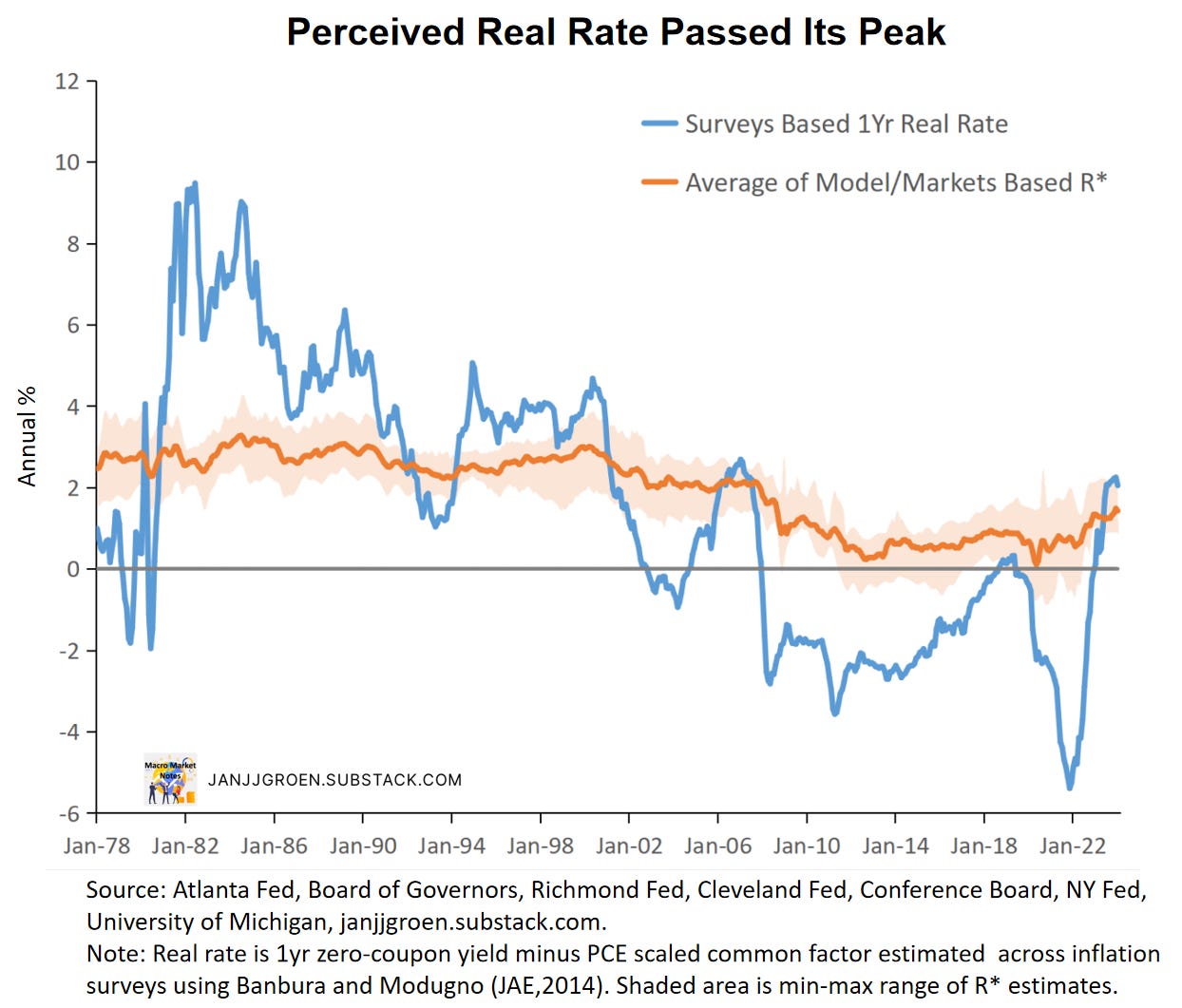

To gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is I published back in August an analysis that focused on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the chart above that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

Key to assessing the restrictiveness of these one-year real rates is where neutral real rates are heading. The chart above is an update of an earlier chart and shows that after close to a decade of ultra-low neutral real rates, these rates have trended up since 2016. These upward trends accelerated further earlier this year, but they have plateaued in the fall with the average across the proxies close to a 1.4% rate.

“I believe policy is set properly. It is restrictive and should continue to put downward pressure on demand to allow us to continue to see moderate inflation readings.” Christopher J. Waller, Almost as Good as It Gets…But Will It Last? (January 16th, 2024).

Judging from Fed official remarks leading up to today’s FOMC decision as well as Chair Powell’s remarks at the post-meeting press conference, the Fed is convinced its policy stance is restrictive enough to bring inflation sustainably back on a path towards 2%. The perceived policy stance as depicted by the survey-based one-year real rate in the chart above only became significantly restrictive (by rising beyond the majority of approximate neutral real rate levels) after the May FOMC meeting. Since then, the expected restrictiveness of the Fed’s policy stance peaked in Q4 and started to ease going into year-end and beyond.

The chart above contrasts my surveys-based one-year real rate relative to the average of model- and market-implied R* estimates with a proxy of the Fed’s view on this real rate gap using information from its own Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). This chart suggests that compared to expectations on “Main Street” and markets, the Fed continues to overestimate somewhat its degree of monetary policy tightening. This is mainly due to FOMC members dialing back their assessments of the neutral real policy rate at the December FOMC meeting.

More importantly, the chart above speaks to a growing concern amongst Wall Street analysts and even some Fed officials that with a continued slowing in spot inflation data real interest rates would continue to rise and endanger the expectation of a “soft landing”. Of course, decisions in the economy are not driven by ex-post real rates (i.e., nominal interest rates minus current realized inflation) but by ex-ante (a.k.a. expected) real interest rates (i.e., nominal interest rates minus expected inflation), as any spending and savings decisions by firms and households reflect those economic actors’ assessment of the inflation-adjusted rates into the future.

Earlier in this post I showed that near-term inflation expectations of firms and households have indeed started to trend down again towards the end of 2023. However, tying this up with where policy and market rates currently sit the chart above makes clear that survey-based expected real interest rates have stabilized, and maybe eased somewhat, going into 2024. With expected real interest rates not trending up it gives the Fed room to be patient in assessing upcoming inflation and labor market data to further assess the current disinflation trend.

Looking Beyond the January FOMC Meeting

Markets have been interpreting the easing in spot inflation data as a sign that Fed funds rate cuts are already forthcoming in Q1 of 2024. In reality, Fed officials are utilizing more of a forward-looking view, based on the expected path of inflation for the year ahead. There are certainly signs of more cooling ahead in underlying inflation trends (especially core services excl. housing inflation) and near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations but expected year-ahead real rates are not rising further and possibly actually easing.

Combine this with a still robust labor market and consumption spending, this means that the Fed can afford to be patient in determining the start date of rate cuts to further assess whether inflation is indeed easing along a medium-term path back to 2%. This is the rationale behind the most important sentence in today’s policy statement:

The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.

My modal view, therefore, remains that we are not going to see a move toward policy rate cuts before mid-2024.

Note, though, that a possible continued rapid disinflation pace in the spot inflation data over the next two to three months, poses a risk that the Fed will feel compelled to already start cutting the Fed funds rate in March. However, with core goods price disinflation possibly being temporary in nature, and still elevated wage growth rates (including today’s release of the Q4 ECI) and consumption spending driving upside risks to the core services inflation outlook it simply seems too early for the Fed to pull the trigger on Fed funds rate cuts in early 2024.