How Tight is the Fed's Interest Rate Policy?

Perceived monetary policy became restrictive over the past three months and more realigned with the Fed's own views. To preserve this, the Fed will turn to 'high for long' and upgrade its 2024 dot.

With Chair Powell’s speech at the 2023 edition of the Jackson Hole symposium in the rearview mirror, I take stock in this note to gauge the Fed’s policy stance and what that means for the remaining FOMC meetings this year.

Key takeaways:

Throughout 2022 and into 2023 the Fed significantly overestimated the restrictiveness of its interest rate policy.

Over the past three months, however, the perceived monetary policy stance has become restrictive and more aligned with the Fed’s own assessment of its stance.

To preserve this, the Fed will focus on ‘high for long’ instead of continued rate hikes and markedly upgrade the 2024 dot in the SEP at the upcoming September FOMC meeting.

Monetary Policy, Interest Rates and Inflation Expectations

To measure the Fed’s policy stance a focus on interest rates at one- or two-year horizons seems appropriate, as it reflects a combination of the current Fed funds rate and the Fed’s signaling regarding future Fed funds rates. It is the persistence of a change in the stance in a certain direction that impacts firms’ and households’ behavior.

Additionally, it is important to focus on inflation-adjusted interest rates. To calculate real interest rates a measure of inflation expectations is needed and these can be derived in a variety of ways across different groups of forecasters. In previous analyses I have focused on using near-term inflation expectations based on surveys drawn from “Main Street”, i.e., firms and households, as these are the most relevant for wage and price setting dynamics and household spending.

The chart above plots five of such “Main Street” measures of one-year ahead inflation expectations, which I consolidate into an aggregate by means of a dynamic factor model using the approach of Banbura and Modugno (JAE, 2014). This measure does incorporate the final revision of the August University of Michigan consumer inflation expectations survey published on August 25th (and which was revised up from 3.3% to 3.5%). The measure shows that “Main Street” one-year ahead inflation expectations eased since peaking around mid-2022 but remain above target with tentative signs that most of the downside adjustment is behind us.

So, to gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is, I will focus on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates based on zero coupon nominal yield curve estimates from the Board of Governors and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the chart above that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

Assessing the Level of Real Interest Rates

The next question is at what level are real interest rates accommodative or restrictive? This very much depends on underlying trends in the economy: there is a real interest rate level where consumption spending, investment spending and savings are in equilibrium, and any deviation from that level will push up or pull-down economic activity. This particular level, often labeled as R*, the neutral interest rate or the equilibrium interest rate, evolves over time in line with long-term trends in economic growth, population growth and the relative supply of government bonds as safe assets that drives the convenience yield of US Treasuries.

Of course, this means that this R* is not observed directly and needs to be inferred indirectly through economic models or financial market data. And this complicates assessing the restrictiveness of real interest rates, or as Chair Powell stated in his 2023 Jackson Hole address:

“We see the current stance of policy as restrictive, putting downward pressure on economic activity, hiring, and inflation. But we cannot identify with certainty the neutral rate of interest, and thus there is always uncertainty about the precise level of monetary policy restraint.” Powell, J. (August 25, 2023), “Inflation: Progress and the Path Ahead”, pp. 7.

The chart above plots five different attempts at determining R*/equilibrium real interest rates:

R* estimates based on the models in Holston, et al. (2017) and Laubach and Williams (2003), where stylized representations of aggregate demand and supply are used to link R* to shifting trends in economic growth.

R* estimate from Lubik and Matthes (2015), who use a less-structured, statistical model that is time-varying to construct 5-years ahead forecasts of the short-term real interest rate.

R* estimate from a large, structural model, a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model, maintained by the Monetary Policy Research group at the New York Fed, as published here.

A forward rate measure representing the five-year ahead expectations for the five-year real interest rate, as derived from zero coupon TIPS yield curve estimates from the Board of Governors. These estimates start in 1999, so pre-1999 I use backcasts for the relevant TIPS-based real interest rates using an approach I co-developed in Groen and Middeldorp (2013).

What is clear from the chart above is that it is really hard to pin down with a lot of certainty the neutral level of real interest rates. Nonetheless, when I take averages of these different R* estimates some trends do become apparent. The average neutral real interest rate estimate decline from around 3.0% until the late 1990s to about 2% in 2006-2007 on the eve of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), as trend economic growth and productivity decelerated.

The average R* estimate dropped further during the GFC to around 0.5%, as the aftermath of the balance sheet recession meant that firms and households persistently cut spending to repair their balance sheets. And as the U.S. economy shed the burden of the GFC and started to normalize, the average R* estimate has been trending back up since 2016 to about 1.2% now.

In the chart above, I compare these R* estimates with my surveys-based one-year real interest rate. It is clear that a given real interest rate level would have had different effects on economic activity at different points in time. For example, despite the large variation in R* estimates it is apparent that in the 1990s the U.S. economy would have been better able to cope with 3% real interest rates than in the current era.

Zooming in on the Current Rate Cycle

The chart above suggests that in the current tightening cycle real interest rates rose above the likely neutral level only very recently. In this last section I will zoom in on the current rate cycle in more detail.

When focusing on the most recent rate cycle, the range of R* estimates from models and financial markets data suggests that R* shifted up in 2022 to above 1% (chart above). How does that compare to the Fed’s own views on the neutral real rate? The Fed’s quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) provides a clue about the range of views within the FOMC on R*, using the central tendency for the longer run Fed funds rate and PCE inflation, respectively.

Until early 2022 there was not much difference between the Committee’s view on the neutral real interest rate and the average level from model- and market-implied estimates. As the chart above shows, it was not until March of this year and beyond that FOMC members began upping their estimates of R*. This came about as economic activity data continued to surprise to the upside, with Committee members publicly doubting policy rates had been restrictive enough:

“The FOMC has significantly raised the target range for the federal funds rate to dampen aggregate demand, but U.S. consumers and businesses are showing remarkable resilience. […] This growth would mean that, so far, tighter monetary policy and credit conditions are not doing much to restrain aggregate demand.” Waller, C. (April 14, 2023), “Financial Stabilization and Macroeconomic Stabilization: Two Tools for Two Problems”, pp. 4.

Next, I look at differentials between one-year expected real rates and assessments of the neutral real rate to measure how restrictive monetary policy is perceived to be. In the chart above, I contrast my surveys-based one-year real rate relative to the average of model- and market-implied R* estimates with a proxy of the Fed’s view on this real rate gap. For the Fed I again use information from SEP reports by using the median forecasts differential for the Fed funds rate and PCE inflation in the following year relative to the central tendencies for the longer run values of these variables.

The chart above makes clear that pre-2022 the Fed was substantially underestimating the degree of monetary accommodation they had instilled on the U.S. economy. Given the lags in monetary policy transmission mechanisms this no doubt was a factor that blunted the impact of the 2022 rate hikes on the economy. And as the Fed pivoted in 2022 towards policy restraint, the chart above also suggests that the Fed overestimated the degree of monetary policy tightening they were imposing on the economy in 2022 and into 2023. There are three factors that drove it:

The Fed’s communication with regard to its future policy rate moves for a long time was rather lacking in 2022 and 2023. While interest rates at one-year maturities and beyond did rise throughout 2022 and 2023, until recently they never fully priced in peak Fed funds rate projections from the Fed’s own SEP.

More optimistic inflation forecasts from the Fed. While the Fed has been expecting PCE inflation to slow below 3% by 2024, “Main Street” inflation expectations, while easing, remain sticky above 3%, and through its impact on wages and price setting has led to slower disinflation than expected, especially for core services prices.

And, as discussed earlier, the Fed has been slow to recognize that the neutral real rate likely shifted up.

Over the last three months, however, the surveys-based real rate gap has become restrictive based on most R* estimates. As a consequence, the chart above suggests that the perceptions regarding monetary policy restraint in the rest of the economy have now become more realigned with those of the Fed.

So, what does this mean for the Fed going forward? A final, ‘maintenance hike’ during the Fall cannot be ruled out in order to realign the peak Fed funds rate as more FOMC members revise upward their neutral real rate estimates. However, real rate gaps finally became restrictive across the economy. The Fed’s focus now will turn to preserving this perceived monetary policy restraint for a meaningful period to achieve a durable disinflation. ‘High for long’ therefore becomes the front line of the Fed’s policy for the months ahead.

While a ‘high for long’ policy does not necessarily preclude Fed funds rate cuts, which would be ‘maintenance cuts’ that maintain the real interest rate at a given level as expected inflation decreases, the Fed will initially be very reluctant to signal too many cuts for the year ahead. The reason for this is twofold. Firstly, a need to durable anchor the Fed funds peak rate level in market interest rate pricing for the year ahead.

Secondly, I use year-ahead inflation expectations of firms and households to measure perceived monetary policy restraint. Research has shown that these types of inflation expectations are the stickiest and often are positively correlated with growth expectations of these same firms and households. Fed signaling aimed at containing these growth expectations therefore could act as a lever to push down “Main Street” inflation expectations further. This, in turn, would then keep real rates elevated and through the direct impact of lower inflation expectations on wage and price setting behavior speed up disinflation, especially for core services prices. Therefore, it is the growth and labor market outlooks that will be the main guide for ‘high for long’ and less so the month-to-month CPI data releases, and Chair Powell clearly spelled that out in his 2023 Jackson Hole speech when discussing the rate outlook.

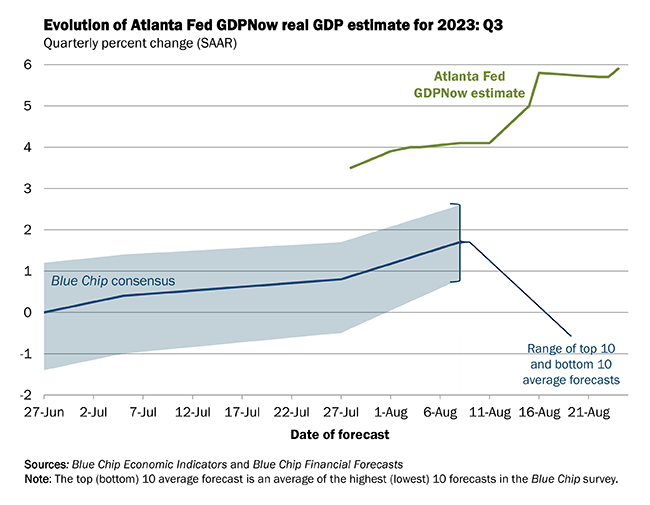

And the growth and labor market outlooks remain, for now, likely too strong for the Fed’s taste. Estimates for GDP growth for 2023 H2 running well above trend levels, see, e.g., the above-trend Q3 GDP Now projections (chart above).

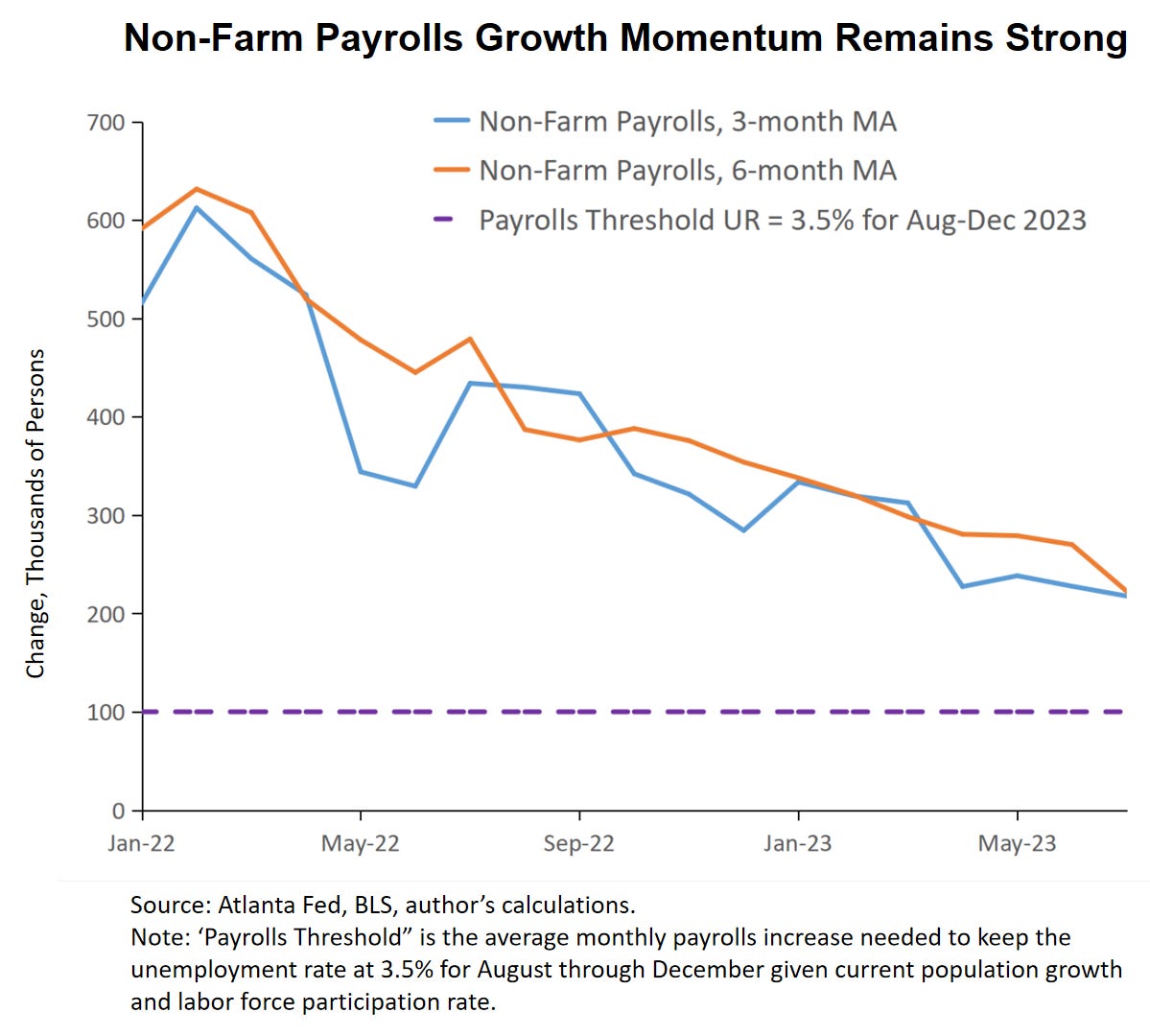

Also, job growth still outpaces population growth, which will keep the unemployment rate below the crucial 4% threshold for the near term (chart above). This all means that the Fed will want to remain appearing on board with a continuation of restrictive interest rate policy.

Hence, the most notable signal that will come out of the upcoming September FOMC meeting will not be whether we have another rate hike or not, but a significant upgrade in the median 2024 Fed funds rate dot when the SEP gets revised. As more FOMC members take out rate cuts from their 2024 Fed funds rate projections, a shift up in the 2024 dot towards a level closer to 5% is likely and markets need to be prepared for this to happen.