Dec Personal Income & Outlays: Carry On Spending

Personal wage income, excess savings and underlying real spending remain strong. Underlying services inflation trends eased again.

The December Personal Income and Outlays report provides premier insights on the U.S. consumer as well as inflationary pressures going forward. This note presents some of these insights.

Key takeaways:

Personal income growth out of wages and salaries remains strong in December and it outpaces the growth rate that is consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium-term.

The stock of excess savings has NOT run out and continues to be a tailwind for consumption. Between November and December, it fell around $39 billion and equaled about $593 billion in December.

Real PCE growth continues to show a strong momentum, with the underlying (trimmed mean) growth rate outpacing the headline rate at an accelerated pace in December. This suggests that consumption will remain strong in 2024 Q1.

Core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, remains at elevated levels on a year/year basis but has continued to slow on a three- and six-month basis.

Despite slowing momentum in non-housing core services inflation, strong wage income growth and real spending will mean the Fed remains wary of starting to cut rates too early in 2024.

Wage Income Growth Remains Strong.

A dominant source of household income is personal income out of wages and salaries. Today’s report showed essentially no revisions in the recent growth of household income out of wages and salaries since the summer.

Compared to the vintage from last month’s report, the pace of year/year income growth out of wages and salaries for May-November was basically unchanged (chart above). For the third consecutive time since June the year/year growth rate accelerated in December, to 6.5% from 6.1% (revised down from 6.2%) in November.

To interpret wage income growth trends, I earlier proposed to compare wage income growth with a neutral benchmark growth rate based on trend non-farm business sector (NFB) output growth and either the abovementioned common inflation expectations factor or the 2% Fed inflation target. Similar to what I did when discussing wages and inflation expectations in my October update, I now also incorporate trend labor share growth into this neutral benchmark.

Any deviation in actual household wage income growth above or below the aforementioned the inflation target-consistent neutral benchmark means household wage income growth outpaces or cannot sustain in the medium term the 2% inflation target.

The chart above shows that momentum in the wage income growth gap based on the Fed’s inflation target accelerated markedly to about +2.1 percentage points, and the three-month averaged version runs at a +1.7-percentage point gap. Nominal wage income growth thus runs at a pace that remains too high to be able to bring inflation back to target in the medium term.

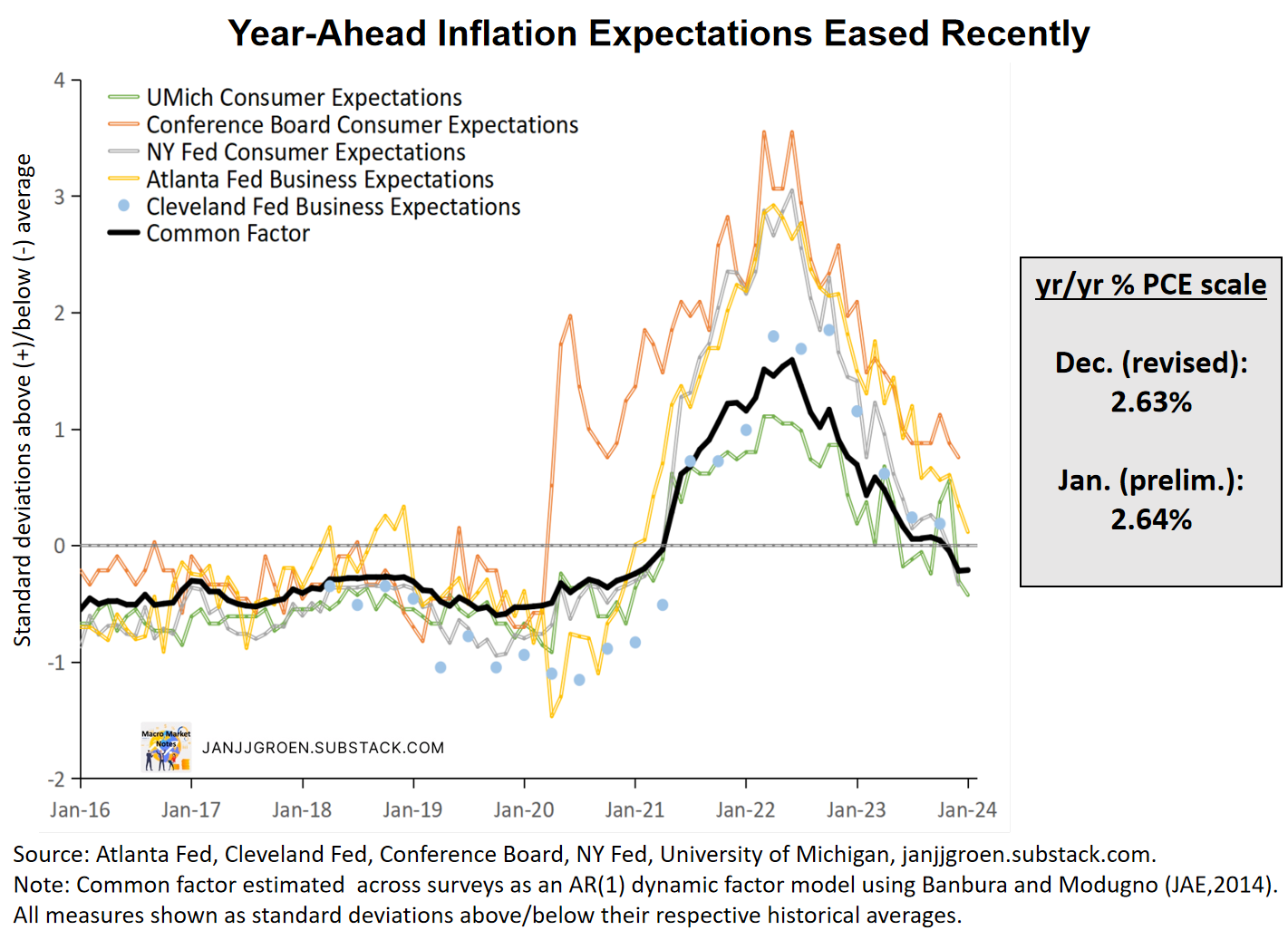

Earlier I showed that the common trend across near-term inflation expectations of firms and households has eased towards the end of 2023 and currently sits at a year/year PCE inflation equivalent rate of 2.6% (chart above). Given the growing gap between personal income out of wages and the medium-term benchmark consistent with 2% inflation, the personal wage income growth pace is also overshooting the medium-run pace that would be consistent with this 2.6% inflation expectation rate. Strong wage income growth therefore remains an upside risk to the medium-term inflation outlook.

With household income growth out of wages and salaries running above the pace consistent with 2% PCE inflation this might be a sign that households’ incomes are likely to remain strong enough to keep consumption spending elevated.

Excess Savings Remain a Tailwind for Households

Household spending was up 0.7% over the month in December, a notably stronger pace compared to disposable household income growth of 0.3% for the same period. As a consequence, the savings rate declined from 4.1% in November (unrevised) to 3.7% in December.

Despite this increase in the savings rate, and typical of what we’ve seen recently, the chart above shows that it remains below my trend savings rate estimate of 5.7% (down from a downwardly revised 5.9% in November) using the ‘average of trend’ approach outlined in my earlier excess savings note (orange line). The actual savings rate had been diverging to the downside relative to this trend savings rate estimate since May, but a lot less so compared to trend savings rate assumptions used elsewhere (grey and yellow lines).

Given the earlier discussed revisions to both personal wage income growth and my estimate of the trend savings rate, in December cumulative excess savings declined from $632 billion in the previous month (upwardly revised from $584 billion) to about $593 billion (see chart above).

In 2023 the pace of drawdowns remained well below the 2022 pace. Compared to 2022 we saw in 2023 that above-trend growth in disposable income, driven by strong wage income growth, partially offsets the drawdowns in excess savings coming from above-trend growth in consumption spending.

Trend Pace in Consumption Spending Remains Strong

Strong income growth out of wages in 2023 allowed households to keep spending at a robust pace without the need to completely run down the stock of excess savings. With wage income growth remaining strong at above inflation target pace, this could mean that real consumption expenditures can be expected to remain relatively high for the near term.

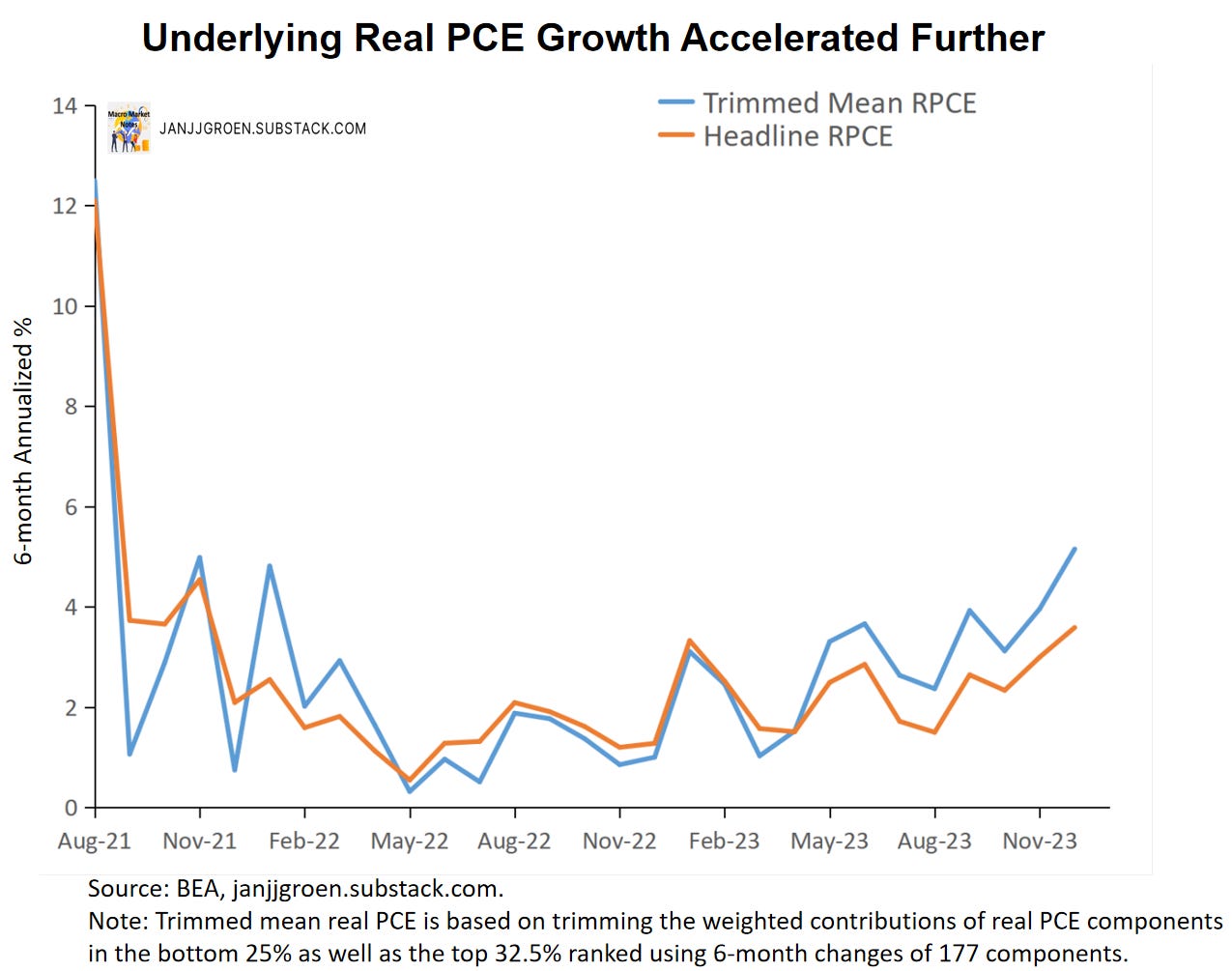

As is the case with headline inflation, headline real consumption spending growth often is driven by volatile components that not always reflect the underlying strength of the economy. A core real consumption spending growth measure, therefore, would be really useful, and I do that by approximating such a core measure based on constructing a weighted trimmed mean across 177 components1 of headline real personal consumption expenditures (PCE).

The chart above shows the resulting trimmed mean real PCE six-month growth rate. It is clear that the trimmed mean measure provides a more accurate reading on the underlying strength of the economy than headline real PCE growth rates, with the trimmed mean measure decreasing ahead of headline growth before the onset of a recession.

When we focus on the more recent period as in the chart above, the six-month annualized headline real PCE growth was basically in line with the trimmed mean six-month growth rate throughout 2022. That changed in 2023 trimmed mean real PCE growth outpacing headline growth, with the gap between the six-month annualized growth rate of trimmed mean real PCE and that of headline PCE increasing since October.

With underlying consumption growth outpacing headline growth in 2023 the economy is far removed from the onset of a recession and in fact shifted to a stronger footing last year. The continued strong pace of trimmed mean real PCE growth likely means that consumption will remain strong going into 2024 Q1.

Easing of Underlying Inflationary Pressures

In terms of inflation, core PCE inflation accelerated in December and stood at a 2.1% annualized monthly rate. Core goods inflation equaled -3.1 % annualized month/month (up from 4.5% in November), whereas core service inflation accelerated for the second consecutive month from 2.7% to about 4% annualized month/month in December.

The Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, core services excl. housing PCE inflation was a main driver behind the above-mentioned December core service inflation acceleration, as it went up from 1.7% annualized month/month to about 3.5%. This could very well be a reflection of adjustments to imputed prices for financial services (especially portfolio management services), as these align well with asset prices which have seen a strong recovery throughout November and December. It is therefore worthwhile to smooth through noisy month-over-month dynamics.

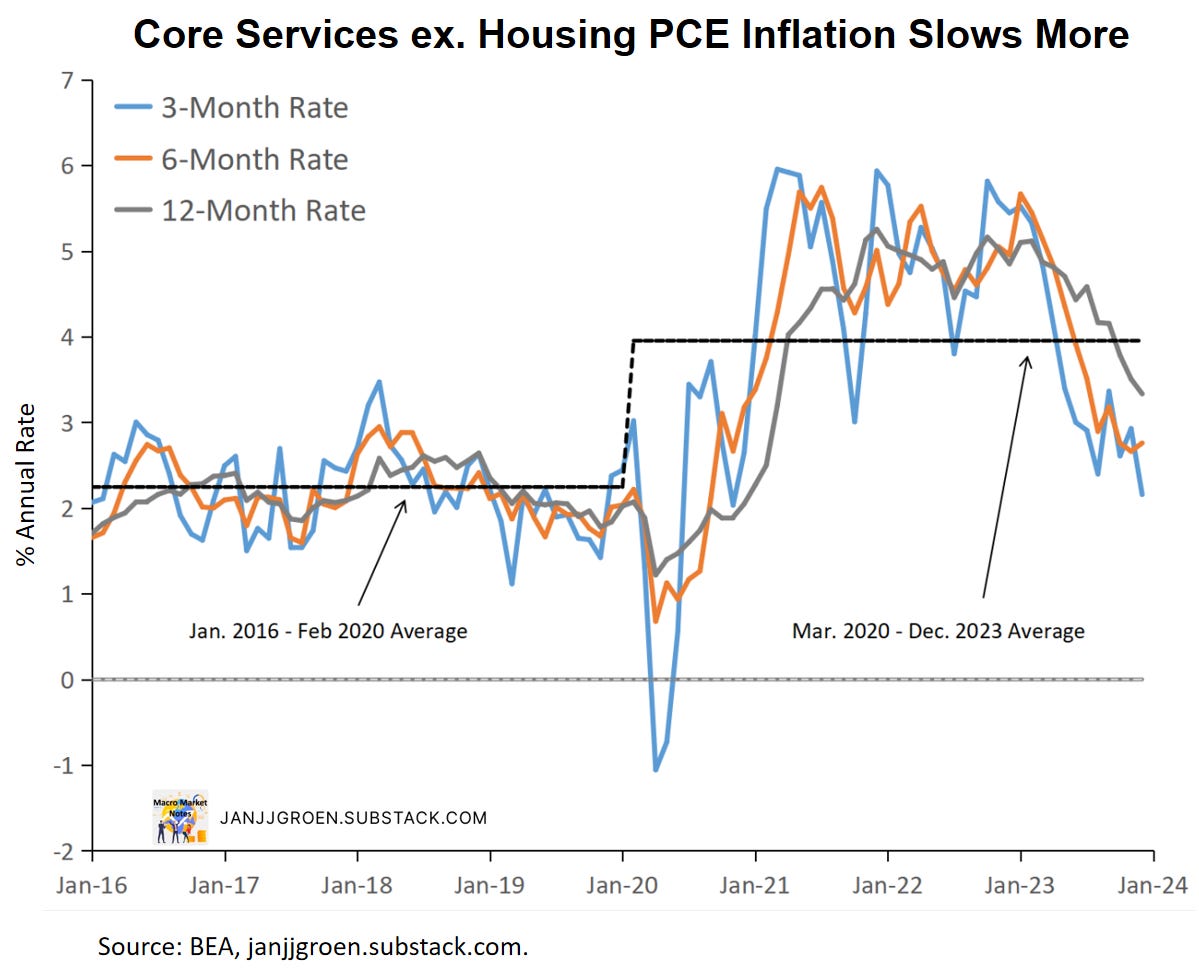

The chart above plots three-, six- and 12-month annualized inflation rates for the non-housing core services PCE deflator. The average annualized monthly rate still reads about 4% for the post-COVID era (black dashed line), twice as a high compared to the average for the immediate years pre-COVID. The momentum measures in the chart above have been sticky around 4% for most of 2023. But in Q4 momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation eased in a sign that it might finally start to break free from the post-pandemic 4% trend.

With households’ wage income growth supportive of above-target PCE inflation over the medium term, a still strong labor market, sizeable stocks of excess savings, and broad-based underlying strength in real consumption spending, conditions continue to be in place that could slow down the disinflation in the core services sector.

The downward momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation in Q4 2023, however, is an encouraging sign for the Fed. It therefore is prudent for the Fed to be patient in dialing down its current restrictive policy stance, with Fed funds rate cuts likely not happening before mid-2024. However, a pick-up in downward momentum in non-housing services inflation into early 2024 Q1 increases the likelihood for rate cuts to commence at the March FOMC meeting.

Thanks for reading Macro Market Notes! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

For a description of these 177 components, see Appendix A in the Dallas Fed trimmed mean PCE inflation working paper.