Wages and Inflation Expectations - October 2023 Update

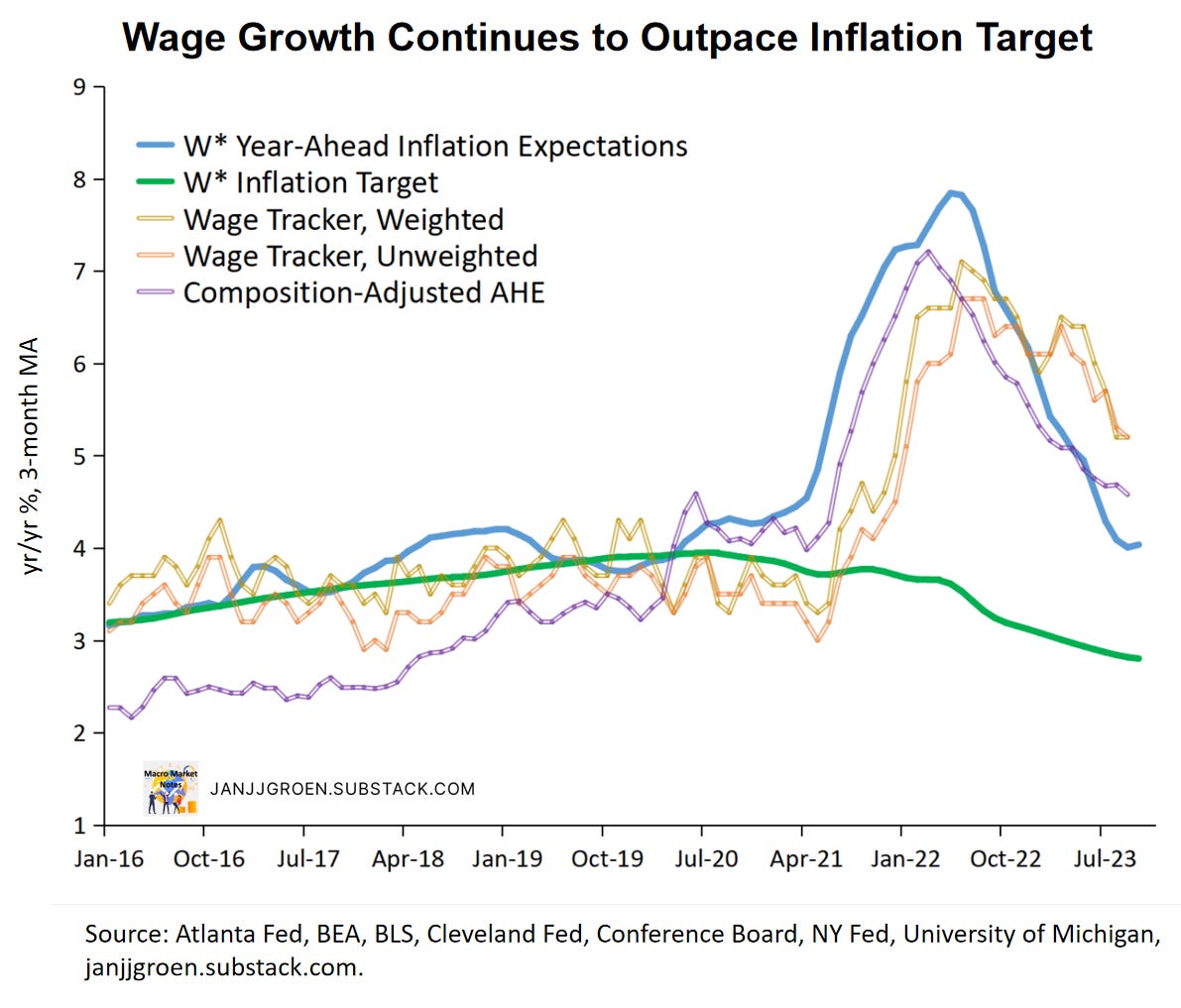

Wage growth remains elevated and overshoots the pace consistent with the Fed's inflation target. "Main Street" inflation expectations remain above 3%.

In a recent note I laid out a simple framework that can be used to interpret wage growth trends relative to inflation expectations and the Fed’s inflation target. The resulting W* measure reflects a trend wage growth rate where demand and supply in the labor market are in balance when expected real wages equal trend labor productivity growth.

Barrow and Faberman (2015), however, note that even in the long run real wage growth not always moves in line with long-run labor productivity and inflation trends, caused by shifts in the long run level of the labor share, i.e., workers’ compensation as a share of business revenue. In particular during and right after the GFC declines in this labor share drove wage growth rates below labor productivity and inflation trends.

Given the volatile moves in the labor share during and after the COVID lockdowns, it seems prudent to adjust my W* measure for long-run labor share shifts. Hence, going forward W* is equal to either the 2% inflation target or year-ahead inflation expectations plus a trend labor productivity growth estimate as well as a trend labor share growth estimate. This corrects my original W* for long-run shifts in the labor share, and as we shall see below this has some unpleasant consequences for the Fed.

With new wage data for September, labor productivity and labor share data for Q2 and updates of inflation expectations data for September and October, this note will update the above-mentioned wage growth framework.

Key takeaways:

Since July, “Main Street” inflation expectations remained broadly stable within the above target 3.1%-3.2% range, with tentative signs of an uptick to 3.3% in October.

Consequently, trend wage growth based on these inflation expectations (W*) no longer is easing, suggesting a floor to how much more wage growth easing might be in the pipeline.

W* is consistent with 3.2%-3.3% PCE inflation, above the Fed’s 2% inflation target. So, any actual further wage growth easing in line with this measure would still keep wage growth at an above-target pace.

Corrected for expected inflation, trend productivity growth and trend labor share growth, wage growth remains a boost for households’ real incomes and spending.

Inflation Expectations

As familiar to some readers, to construct the W* trend wage growth measure, I focus on inflation expectation surveys drawn from “Main Street”, i.e., five inflation expectations samples from households and firms. Since the last note, four out of these surveys got updated with September now being complete and two surveys providing expectations for October (the Atlanta Fed survey on Oct. 11 and the preliminary University of Michigan Survey results on Oct. 13).

In terms of the two October results, the preliminary median one-year ahead inflation expectations from the University of Michigan Consumer Survey ticked up markedly (from 3.2% in Sep. to 3.8% for early Oct.) and the corresponding median of the Atlanta Fed Business Inflation Expectations Survey ticked down ever so slightly. As explained in my original W* note, these inflation survey measures are aggregated by means of a single dynamic common factor that depends on its own lag using the approach of Banbura and Modugno (JAE, 2014).

The updated individual expectations series are plotted in the chart below alongside the updated, estimated common factor across these series. After scaling the factor in year-on-year PCE inflation terms, inflation expectations got slightly revised up for September from previously 3.18% to about 3.22%. The preliminary estimate for October currently suggests inflation expectations might be around 3.30%. All told, it seems “Main Street” inflation expectations have been relatively stable around 3.2% since July.

Trend Labor Productivity and Labor Share Growth Rates

The release of the BLS's "Productivity and Costs" report for Q2 garnered a lot attention, as quarter-on-quarter labor productivity growth bounced back substantially in Q2 relative to Q1. After updating my own estimate of trend labor productivity in the nonfarm business sector, the year/year trend labor productivity growth for Q1 remains subdued historically, as the chart below makes clear.

The labor share equals the ratio of total workers compensation relative to nominal output of businesses. The BLS's "Productivity and Costs" report also provides information on this labor share for the nonfarm business sector through Q2 2023. As for labor productivity, I approximate the labor share trend by taking the average of six trend estimation methods applied to the actual labor share data, as outlined in my original W* note.

The chart below shows this labor share trend estimate. Leading up and right after the GFC the trend labor share declined sharply, and then started to rise again from 2015. More recently, however, the labor share trend has drifted down again. Potentially, this could mean that the Fed needs to see even lower wage growth levels than originally estimated to have these rates in line with its inflation target.

Wage Growth

I now combine the following three ingredients,

The trend productivity growth estimate described earlier (assuming a Q3 trend labor productivity level based on the average quarterly trend productivity changes over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

A similar estimate of trend labor share growth (assuming a Q3 trend labor share level based on the average quarterly trend productivity changes over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

And, either the year-ahead inflation expectation proxy based on the common factor from surveys or the 2% inflation target.

This will result in two alternative trend wage (W*) measures, and I compare these, as usual, with Atlanta Fed wage tracker wage series that measure average hourly wages of workers that are robust to compositional changes over the month.

The average hourly earnings (AHE) wage series from the BLS Employment Situation report usually gets a lot attention, particularly this month as it eased markedly. Unlike the Atlanta Fed wage tracker series, however, the AHE series is prone to excess volatility owing to the impact of the composition of payrolls growth over the month. A big chunk of the September payrolls increase was driven by strong jobs growth in the leisure and hospitality sector, a sector generally on the lower end of the wage distribution, so no wonder we saw the sizeable slowdown in AHE occurring.

Fortunately, Pat Higgins from the Atlanta Fed has been constructing an AHE series that adjusts up to a certain extent the headline AHE series for compositional changes, both across sectors and types of workers, which can be found here. Indeed, the chart below shows that this composition adjustment makes the AHE series a lot less volatile and suggests a somewhat more gradual wage growth easing recently compared to the headline series.

Therefore, from hereon I will compare both Atlanta Fed wage tracker series as well as the composition-adjusted AHE series with my W* measures - see the chart below. As in previous months, the chart continues to suggest that wage growth overshot the expectations-based W* metric, suggesting positive expected real wage growth throughout the first three quarters of 2023 and into Q4. Note, though, that both actual wage growth as well as the expectations-based W* measure remain still above a level that is consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target and are more consistent with 3%-4% PCE inflation rates. With the declining trend in the labor share incorporated into the W* measure, the Fed needs to see year/year wage growth of barely 3% for it to be consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium term.

An important wage pressure gauge for the Fed is the quarterly ‘Employment Cost Index’ (ECI), another wage measure that corrects for compositional changes, of which we get the Q3 release later this month on the first day of the next FOMC meeting (Oct. 31). The W* framework can be used to quantify what drove ECI wage growth to be at an above-inflation target pace.

More specifically, I define an ECI wage growth gap as the difference between wage growth for ECI based on wages and salaries in the private sector and a quarterly version of the green W* line (reflecting trend wage growth in line with 2% PCE inflation) in the chart above. Then I construct differences between “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations relative to 2%, between actual and estimated trend labor productivity growth, and between actual and estimated trend labor share growth, respectively. These I subsequently use to decompose the ECI wage growth gap relative to the inflation target pace into an inflation expectations gap, a labor productivity gap, a labor share gap, and an unexplained rest term (“Other”).

The chart below depicts the result of this ECI wage growth gap decomposition. Not surprisingly, during and right after the COVID lockdowns the ECI gap was heavily affected by (often offsetting) large swings in labor productivity and labor share gaps as well as the unexplained part. Since mid-2021 the ECI gap has been persistently positive (above a pace consistent with 2% over the medium term), as the inflation expectations gap turned positive in a sizeable way.

The recent easing in the ECI gap can also be attributed to some easing in this inflation expectations gap. Given that “Main Street” year-ahead inflation expectations eased further in Q3, from about 3.7% to about 3.2% (PCE year/year terms), we should expect Q3 ECI to have eased further as well. As discussed above, though, there doesn’t seem to be any indication that beyond Q3 “Main Street” inflation expectations have eased further and rather remain stuck above inflation target levels. Thus, beyond Q3 going into Q4 and beyond, we should not expect to get a lot more easing in the ECI wage growth measure, which is a worry for the Fed.

Implications

The 2023 overshoot of wages relative to expectations-based W* in the charts above are partly driven by the decline in this W* as inflation expectations eased further throughout the year. This is in itself a good trend for the Fed, as the downward move in this W* suggests that a continued easing trend in wage growth could be possible for the remainder of the year. This trend wage growth, however, is consistent with an above-target 3+% inflation rate. And the data on “Main Street” inflation expectations do suggest that, for now, the downward adjustment in expectations is behind us, providing a floor under how much more wage growth will be likely to ease further.

The positive expected real wage growth rate seen throughout 2023 owing to a strong labor market, likely will boost expected real wage incomes of household. This will keep consumption at robust levels (see also my recent PCE note), and with the ongoing rotation of consumption back to services this could in particular result in upward pressures in core services prices to persist. In turn this could keep inflation expectations at above target levels and, thus, the rate of trend wage growth.

This interplay between labor market strength and solid consumption spending is a major driver for the Fed’s behavior going into 2024. A consequence of this is that the Fed has become a lot less sensitive to spot inflation data, and more focused on labor market, consumption and economic growth data. The goal is to get the economy to grow at a below trend rate, which will bring down “Main Street” near term inflation expectations more in line with 2% inflation, and thus also wage and spending growth rates.