August Personal Income & Outlays: The Consumer Marches On

Personal wage income was revised up and the underlying real spending pace remains strong. Underlying inflation trends remain sticky at above-target levels.

The August Personal Income and Outlays report provides some valuable insights on the U.S. consumer as well as inflationary pressures going forward. This note sketches out some of these insights.

Key takeaways:

Personal income growth out of wages and salaries was revised up significantly for 2023 and runs at a pace that can comfortably sustain a 3.2% PCE inflation for the year ahead.

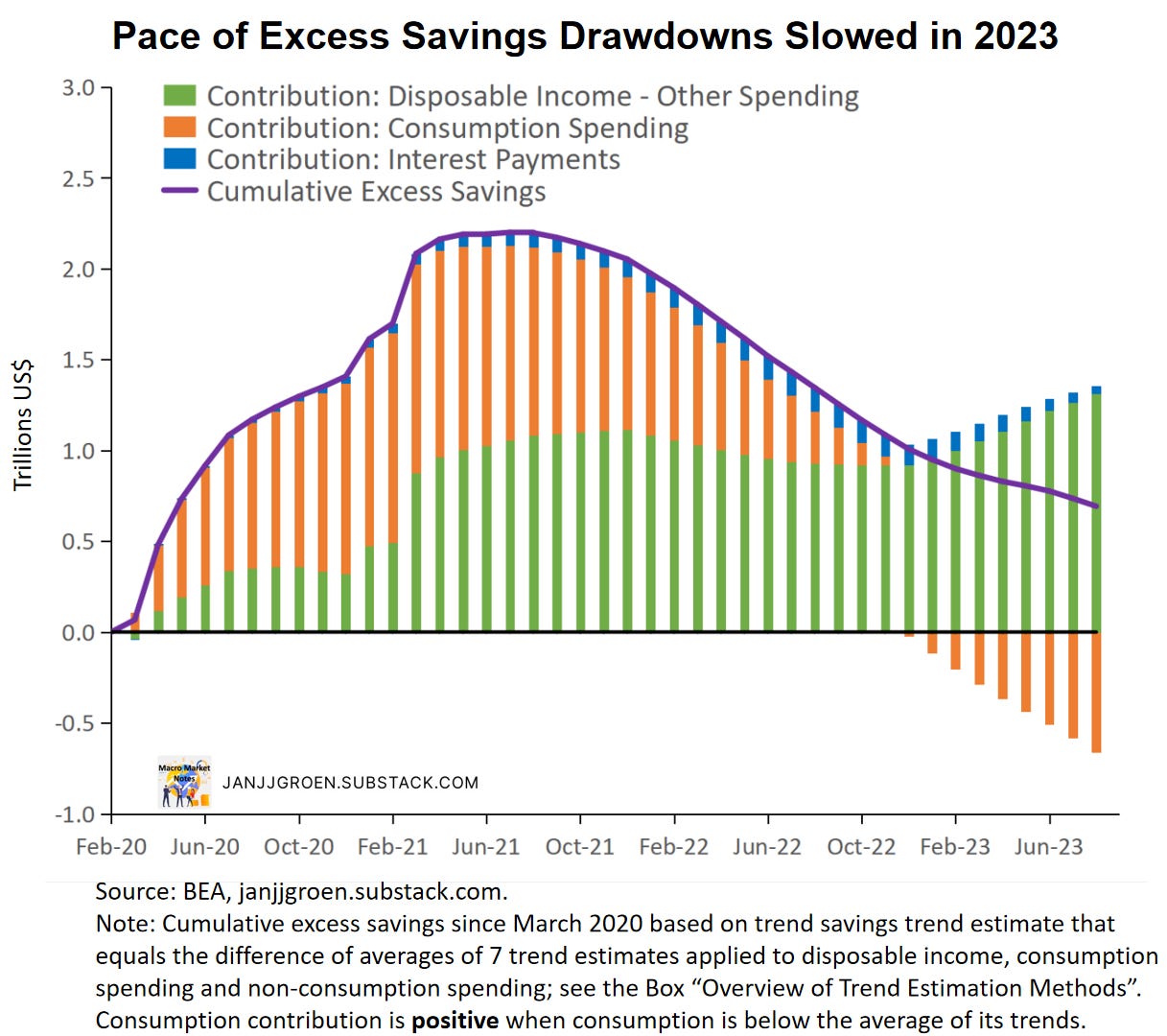

The stock of excess savings, however, still has not run out and, in fact, was revised up substantially. Between July and August, it fell about $43 billion, as disposable income continues to run above trend, and equaled $693 billion in August.

Real PCE growth continues to show a solid momentum, with broad-based underlying strength since May. This suggests that real consumption expenditures should continue to expand at a solid pace for at least the remainder of the year.

Above developments explain the strong momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, and going forward this not likely to dissipate soon.

Wage Income Growth Stronger than Expected.

A lot of the news in the August Personal Income and Outlays report was due to a comprehensive benchmark revision of the recent past. One consequence was a marked upward revision in 2023 personal income growth owing to wages and salaries.

While income growth out of wages and salaries for 2022 was somewhat revised down, 2023 saw large upward revisions with, for example, an upward revision for July from 4.6% based on the August vintage to 5.9% in the current vintage (chart above).

Today (September 29th) we also had the final revision of the September inflation expectations from University of Michigan Consumer Survey. Firms’ and households’ year-ahead inflation expectations for September remained around 3.2% in PCE year-on-year inflation terms, a level where it has been since July (chart above). This is quite a bit above the Fed's 2% inflation target and given that these expectations are a main input in wage and price setting behaviors, further disinflation towards 2% might not be so easy going forward compared to what we’ve seen in the inflation data this summer.

To interpret wage income growth vs. elevated inflation expectations, I earlier proposed to compare wage income growth with a neutral benchmark growth rate based on trend non-farm business sector (NFB) output growth and either the abovementioned common inflation expectations factor or the 2% Fed inflation target. Any deviation in actual wage income growth above or below the neutral benchmark means wage income growth outpaces or cannot sustain in the medium term either year-head inflation expectations or the inflation target.

The chart above show that after the benchmark revisions, the wage income growth gap based on the “Main Street” year-ahead inflation expectations closed in August. This means that wage income growth now runs at a pace that can sustain the August 3.2% year-head expectation for PCE inflation over the medium term. Also, when you smooth the data, this gap now has been slightly positive since May. Note, however, that momentum in the wage income growth gap based on the Fed’s inflation target is still positive, as three-month averaged smoothing of wage income growth still has been too high to be able to bring PCE inflation back down to 2% over the medium term.

The recent strength in household income growth out of wages and salaries relative to elevated inflation expectations might be a tentative sign that for now households’ incomes is likely to remain strong enough to keep spending running at a solid pace going forward.

Overall Household Spending Remains Strong

Household spending was up 0.4% over the month in August, in line with the household income growth rate. As a consequence, the savings rate dropped from 4.1% in July to 3.9% in August.

As can be observed from the chart above, this savings rate drop to 3.9% in August was below my trend savings rate estimate of about 6.2% using the ‘average of trend’ approach outlined in my earlier excess savings note. Based on the benchmark revisions, the actual savings rate has been diverging to the downside relative to this trend savings rate estimate since May. So, what does this mean for the elusive excess savings of households?

Households still have excess savings left to fall back on (chart above). After the comprehensive benchmark revisions in the September vintage, the stock of excess savings was revised up for the pre-August data, with, for example, July excessive savings being revised up from about $634 billion to $736 billion.

In August cumulative excess savings declined from $736 billion to about $693 billion. This is the result of above trend growth in disposable income, driven strong wage income growth, partially offsetting the drawdowns in excess savings coming from above trend growth in consumer spending. Note also that the positive contribution of interest payments to cumulative excess savings. This has been declining over the past few months but despite rising interest rates households’ interest payments1 continue to increase at a below trend pace.

Solid Underlying Pace in Consumption Spending

The solid pace of income growth out of wages in 2023 has allowed households to keep up an equally solid pace of inflation-adjusted spending without the need to completely run down the stock of excess savings. With wage growth slowing but still remaining strong at above inflation target pace, this could mean that real consumption expenditures can be expected to remain relatively high for the near term.

Real consumption growth can be expected to exhibit strong underlying momentum if this strength is broad-based across its subcomponents. To get gauge of this underlying momentum I construct the weighted median of real personal consumption expenditures, where the monthly changes in 177 subcomponents of real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) are ranked followed by trimming the weighted contributions of the real PCE subcomponents that in the bottom 25% as well as the top 25%. The chart above shows the six-month annualized growth rate in this median real PCE in comparison to the headline real PCE. It suggests that the strength of real consumption in 2022 was not that broad-based, but this has changed since May of this year as strong real headline PCE growth has become more underpinned by broad-based underlying consumption spending strength.

Going forward, still strong momentum in the pace of median real PCE growth suggests that consumption spending is likely to remain strong for at least the remainder of the year (chart above).

Underlying Inflationary Pressures Remain Strong

With the comprehensive benchmark revision in this report, the Fed also got an unpleasant message with regards to the underlying inflationary pressures in the economy. Sure, core PCE inflation slowed, especially on account of core goods inflation that, for now, seems to have moderated somewhat. But when the focus shifts to one of the Fed’s favorite gauges of underlying inflation, core services excl. housing PCE inflation, momentum is still strong and in line with a “core-of-core” PCE inflation trend that is almost twice as high compared to the pre-COVID years.

With households’ wage income growth supportive of above-target PCE inflation over the medium term, still sizeable stocks of excess savings, and broad-based underlying strength in real consumption spending, it is likely that in particular core services inflation will remain sticky around above-target trends. Given these developments it’s unlikely to expect the Fed to step away from its restrictive stance any time soon. It also underscores that the fact that since the May FOMC meeting the Fed has become less sensitive to spot inflation data and shifted its focus even more towards the degree of strength in labor market and consumption data.

Interest payments in the Personal Income & Outlays Report exclude mortgage interest payments.