Sep Personal Income & Outlays: What Headwinds?

Personal wage income and underlying real spending growth rates remain strong. Underlying inflation trends continues to be sticky at above-target levels.

The September Personal Income and Outlays report provides some valuable insights on the U.S. consumer as well as inflationary pressures going forward. This note sketches out some of these insights.

Key takeaways:

Personal income growth out of wages and salaries slowed in September but continues to run at a pace that can sustain a 3+% PCE inflation rate for the year ahead.

The stock of excess savings has NOT run out and provides another tailwind for consumption. Between August and September, it fell about $49 billion, as disposable income continues to run above trend, and equaled about $700 billion in September.

Real PCE growth continues to show a strong momentum, with the underlying (trimmed mean) growth rate outpacing the headline number since April. This suggests that there is enough underlying strength in the U.S. economy to likely keep GDP growth in Q4 at an above trend pace.

Given above developments it’s not surprising that momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, remains strong and even showed some acceleration. Going forward this is not likely to dissipate soon.

Wage Income Growth Stronger than Expected.

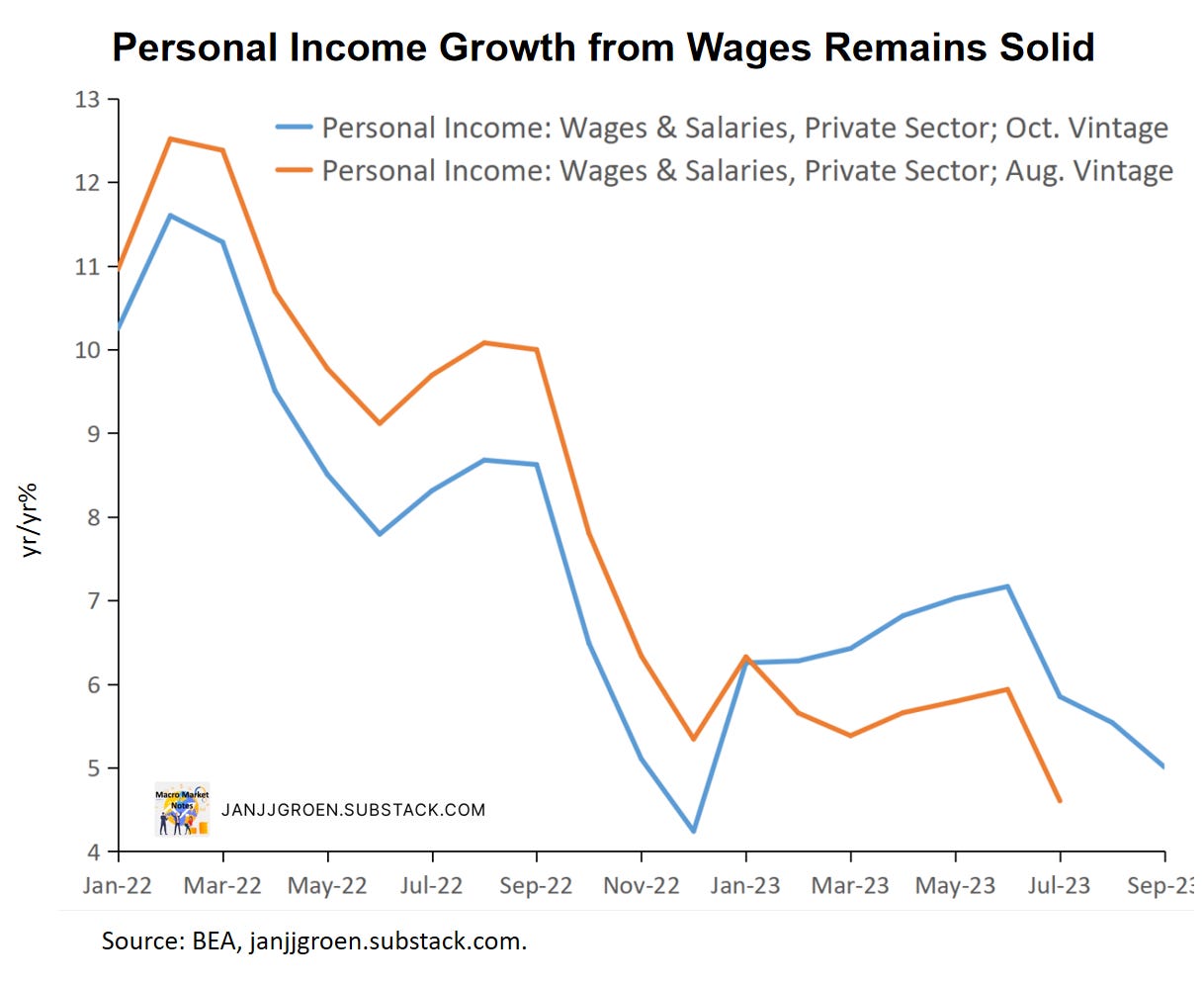

A lot of the news in the August Personal Income and Outlays report was due to a comprehensive benchmark revision of the recent past, which led to marked upgrade in the growth of household income out of wages and salaries for 2023.

Since June the pace of income growth out of wages and salaries has slowed with the year/year slowing further in September to 5% from about 5.5% in August. This still is somewhat higher than the growth rates we observed at the end of 2022 (chart above).

Today (October 27th) we also had the final revision of the October inflation expectations from University of Michigan Consumer Survey, with year-ahead expectations from this survey being revised up from a preliminary 3.8% to 4.2%. Firms’ and households’ year-ahead inflation expectations for October consequently shifted up somewhat to around 3.4% in PCE year-on-year inflation terms, compared to the 3.2% level around which these expectations had settled during July - September (chart above). This is quite a bit above the Fed's 2% inflation target and given that these expectations are a main input in wage and price setting behaviors, further disinflation towards 2% might be stalling.

To interpret wage income growth vs. elevated inflation expectations, I earlier proposed to compare wage income growth with a neutral benchmark growth rate based on trend non-farm business sector (NFB) output growth and either the abovementioned common inflation expectations factor or the 2% Fed inflation target. Similar to what I did when discussing wages and inflation expectations in my October update, I now also incorporate trend labor share growth into this neutral benchmark. Any deviation in actual wage income growth above or below the neutral benchmark means wage income growth outpaces or cannot sustain in the medium term either year-head inflation expectations or the inflation target.

The chart above shows that with the slowing in personal wage income growth in September, the wage income growth gap based on the “Main Street” year-ahead inflation expectations became slightly negative with the smoothed three-month moving average remaining just above zero. This means that wage income growth continues to run at a pace that can sustain 3+% year-head expectations for PCE inflation over the medium term. Note, however, that momentum in the wage income growth gap based on the Fed’s inflation target is still positive, as three-month averaged smoothing of wage income growth still has been too high to be able to bring PCE inflation back down to 2% over the medium term.

With household income growth out of wages and salaries running in line with elevated inflation expectations this might be a tentative sign that for now households’ incomes are likely to remain strong enough to keep spending running at a solid pace going forward.

Underlying Household Spending Remains Strong

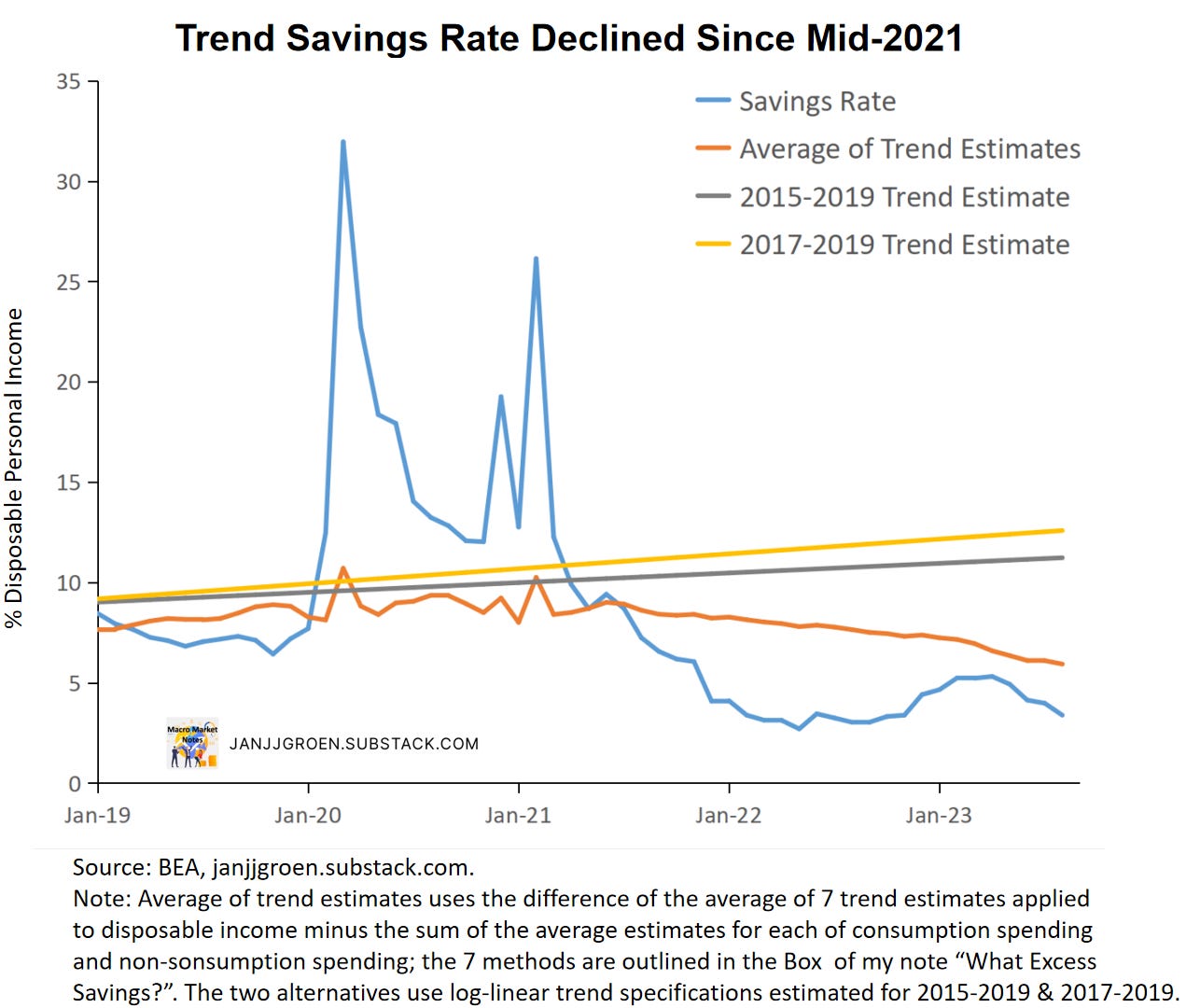

Household spending was up 0.9% over the month in September, far outpacing household income growth of 0.3%. As a consequence, the savings rate dropped from 4% in August to 3.4% in September.

As can be observed from the chart above, this savings rate drop to 3.4% in September was below my trend savings rate estimate of about 5.9% (down from a revised 6.1% in August) using the ‘average of trend’ approach outlined in my earlier excess savings note. The actual savings rate has been diverging to the downside relative to this trend savings rate estimate since May. So, what does this mean for the elusive excess savings of households?

Given an upward revision in August disposable income and the shift down in the estimated trend savings rate, in September cumulative excess savings declined from $753 billion to about $703 billion (see chart above). This is in line with the pattern seen so far in 2023: above trend growth in disposable income, driven by strong wage income growth, partially offsetting the drawdowns in excess savings coming from above trend growth in consumer spending. Note also that the positive contribution of interest payments to cumulative excess savings. This has been declining over the past few months but despite rising interest rates households’ interest payments1 continue to increase at a below trend pace.

Solid Underlying Pace in Consumption Spending

The solid pace of income growth out of wages in 2023 has allowed households to keep up an equally solid pace of inflation-adjusted spending without the need to completely run down the stock of excess savings. With wage growth slowing but still remaining strong at above inflation target pace, this could mean that real consumption expenditures can be expected to remain relatively high for the near term.

As is the case with headline inflation, headline real consumption spending growth often is driven by volatile components that not always reflect the underlying strength of the economy. A core real PCE spending growth measure, therefore, would be really useful.

To construct such a core measure, I follow a similar procedure as used to determine the Dallas Fed trimmed mean PCE inflation rate: I construct a weighted trimmed mean across 177 components2 of headline real personal consumption expenditures, by dropping the lowest and highest growth rates and reweighting the remaining components. The appropriate trimming points for 1-month, 3-month, 6-month and one-year trimmed mean real PCE growth rates are determined by minimizing for each the distance relative to corresponding growth rates based on an average of trend real PCE estimates across a similar range of estimation methods as I’ve used to estimate the trend savings rate.

The two charts above show the resulting trimmed mean real PCE six-month and one-year growth rates. The charts make clear that the trimmed mean measures provide a more accurate reading on the underlying strength of the economy than headline real PCE growth rates, and in case of the six-month trimmed mean rate it also has some mild leading indicator properties.

The chart above shows the six-month annualized trimmed mean real PCE growth rate in comparison to the headline real PCE over the recent period. It suggests that while the strength of real consumption in 2022 was basically in line with the underlying growth rate, in 2023 trimmed mean real PCE growth outpaced headline growth suggesting that the economy shifted to stronger footing this year, which now finally appears to be reflected in the official (GDP) data.

Going forward, the strong momentum in the pace of trimmed mean real PCE growth suggests that consumption spending is likely to remain strong for at least the remainder of the year.

Underlying Inflationary Pressures Remain Strong

In terms of inflation, core PCE inflation accelerated, especially on account of core services inflation. When we focus one one of the Fed’s favorite gauges of underlying inflation, core services excl. housing PCE inflation, it remains high and has been gaining momentum since the summer. “Core-of-core” PCE inflation continues to show a trend that is almost twice as high compared to the pre-COVID years.

With households’ wage income growth supportive of above-target PCE inflation over the medium term, still sizeable stocks of excess savings, and broad-based underlying strength in real consumption spending, in particular core services inflation will remain sticky around above-target trends. Given these developments it’s unlikely to expect the Fed to step away from its restrictive stance any time soon. It also underscores that the fact that since the May FOMC meeting the Fed has become less sensitive to spot inflation data and shifted its focus even more towards the degree of strength in labor market and consumption data.

Interest payments in the Personal Income & Outlays Report exclude mortgage interest payments.

See Appendix A in the Dallas Fed trimmed mean PCE inflation working paper.