Sep FOMC Meeting: How Far Down?

The Fed cut rates by 50bps and signaled 150bps further easing by 2025. However, by March neutral rate uncertainty means a murkier rate outlook for the rest of 2025.

The public debate about the size of the September cut got finally settled today, as the Fed cut its policy rate by 50bps. More importantly, the forward guidance embedded by the update to the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) as well as the post-meeting remarks from Chair Powell suggests the move was part of a catch-up in rates to ease excessive restrictiveness before year-end. Beyond 2024, the Fed signals an easing path for next year with most of the easing concentrated in Q1 in order to get closer to potential neutral rate range.

Key takeaways:

The FOMC decided to lower the Fed funds target range from 5.25%-5.50% to 4.75%-5%, with Governor Bowman dissenting and favoring a 25bps cut instead. The updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) signaled a bias to continue to lower rates to 3.25%-3.50% by the end of 2025.

Near-term underlying PCE inflation trends likely moved further below 2.5% in August, consumption spending remained strong, and labor market activity in August recovering relative to July and suggest cooling towards stability of the unemployment rate in the low 4% range. This suggests slowing economic growth rather than a recession remains the correct base case.

A variety of policy rate rules suggest that, as of August, the Fed funds target was about 100bps too high. With today’s rate cut, the Fed made up a decent chunk of this deviation. With the updated SEP 2024 Fed funds projection now at 4.4% this suggests that in the near-term the Fed is focused on catching up towards a more appropriate rate level.

Under the base case of a gradually slowing economy and inflation moderation for Q4 and beyond, the new SEP Fed funds rate projection suggests that after today we’ll likely see consecutive 25bps rate cuts between now and March for a total of about 100bps worth of further easing.

Beyond the March 2025 FOMC meeting, uncertainty regarding the neutral Fed funds rate level, both in terms of the data as well as disagreements within the FOMC, will mean a more cautious rate cutting path for the remainder of 2025.

Preamble

The July Personal Income & Outlays report showed a more pronounced slowing momentum for non-housing core services PCE inflation. The trimmed mean measures of PCE inflation similarly slowed to around 2.4% on a six-month basis. While the month-over-month developments in the August CPI report showed some firming in core CPI inflation, a lot of that happened owing to strong housing services inflation, which still shows no signs of a widely anticipated downtrend. Indeed, measures of underlying CPI inflation (i.e., Median and 16% Trimmed Mean CPI) held steady over the month in August despite the tick up in core inflation.

Averaged over six months these underlying CPI inflation series moved closer to the Fed's 2% inflation target (chart above). One can use the strong correlations between these underlying CPI inflation measures and their PCE equivalents in a state space dynamic factor model to get statistical nowcasts of Median and Trimmed Mean PCE inflation. And at the time of the August CPI report the nowcasted trimmed mean PCE inflation rates continued to run further below 2.5% on a six-month basis in August and ever so closer to 2% (diamonds in the chart above).

With underlying inflation rates moving more decisively back towards target over the near term, “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations eased as well throughout Q3. When I extract the common trend across a variety of firm and household surveys of near-term inflation expectations for August and September (including the Atlanta Fed BIE and preliminary University of Michigan surveys published today and last week), it is clear that those expectations eased back towards the trough observed in Q1 (chart above). Bottom line is that the recent easing inflation appears to be broad-based, which is good news for the Fed.

The July jobs report struck like lightening with payrolls growth slowing and the unemployment rate rising significantly. However, there were a number of temporary factors underlying this downbeat report, some of which were bound to be reverted in August. And the August jobs report indeed confirmed that the downbeat July labor data were likely a one-off. Payrolls growth accelerated relative to July, but the underlying trends were slowing, and the unemployment rate ticked down from 4.3% to 4.2%. The best news in the August jobs report was to be found in the data on total and short-term unemployed and employed persons, which suggested a significant improvement of the job-finding rate for July, with a 52% probability an unemployed person in July was no longer unemployed by August.

The above suggests it seems more likely that the labor market is cooling towards a state consistent with a relatively stable unemployment rate of just over 4% rather than a forthcoming recession. This would also be more in line with indicators of consumption spending with, for example, strong inflation-adjusted retail spending activity on goods showing growth rates that have been accelerating since the first half of the year (chart above). This bodes well for inflation-adjusted spending growth in the more complete August Personal Income & Outlays report later this month, and the resulting healthy pace of household spending signals that a recession, for now, should not be a base case for the U.S. economy.

How Restrictive Is the Fed?

To gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is I published back in August 2023 an analysis that focused on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the chart above that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

The perceived policy stance as depicted by the survey-based one-year real rate in the chart above only became significantly restrictive (by rising beyond the majority of approximate neutral real rate levels) by the summer of 2023. Until recently, the expected restrictiveness of the Fed’s policy stance hovered at highs not seen since Q4 2000. However, since the July FOMC meeting Fed officials publicly announced an impending start of a rate cutting cycle, resulting in a notable easing of the Fed’s perceived policy stance: in June one-year real rates ran around 100bps (120bps) above the average (median) R*, which got halved by August and going into September these real rates now only overshoot the average (median) R* by about 25bps (44bps).

The Fed’s Own View

FOMC members updated their forecasts for inflation, growth the unemployment rate and the Fed funds rate at this meeting. The inflation outlook was modified relative to June, especially for 2024 where 2024 Q4/Q4 core PCE inflation projection was downgraded to 2.6% from 2.8% previously. Beyond 2024 the Q4/Q4 core PCE inflation projections moved down a lot less for 2025 from 2.3% to 2.2%. The SEP projections for the unemployment rate moved up substantially relative to the June SEP: from 4% to 4.4% in 2024, and from 4.2% to 4.4% in 2025.

The median Fed funds projection for 2024 in this updated SEP dropped 75bps relative to June, from 5.1% to 4.4% from one rate cut to three cuts. With today’s 50bps rate cut this suggests 50bps additional rate cuts for the remainder of the year. For 2025 the SEP suggests an additional 100bps in rate cuts towards a 3.4% Fed funds rate by end-2025.

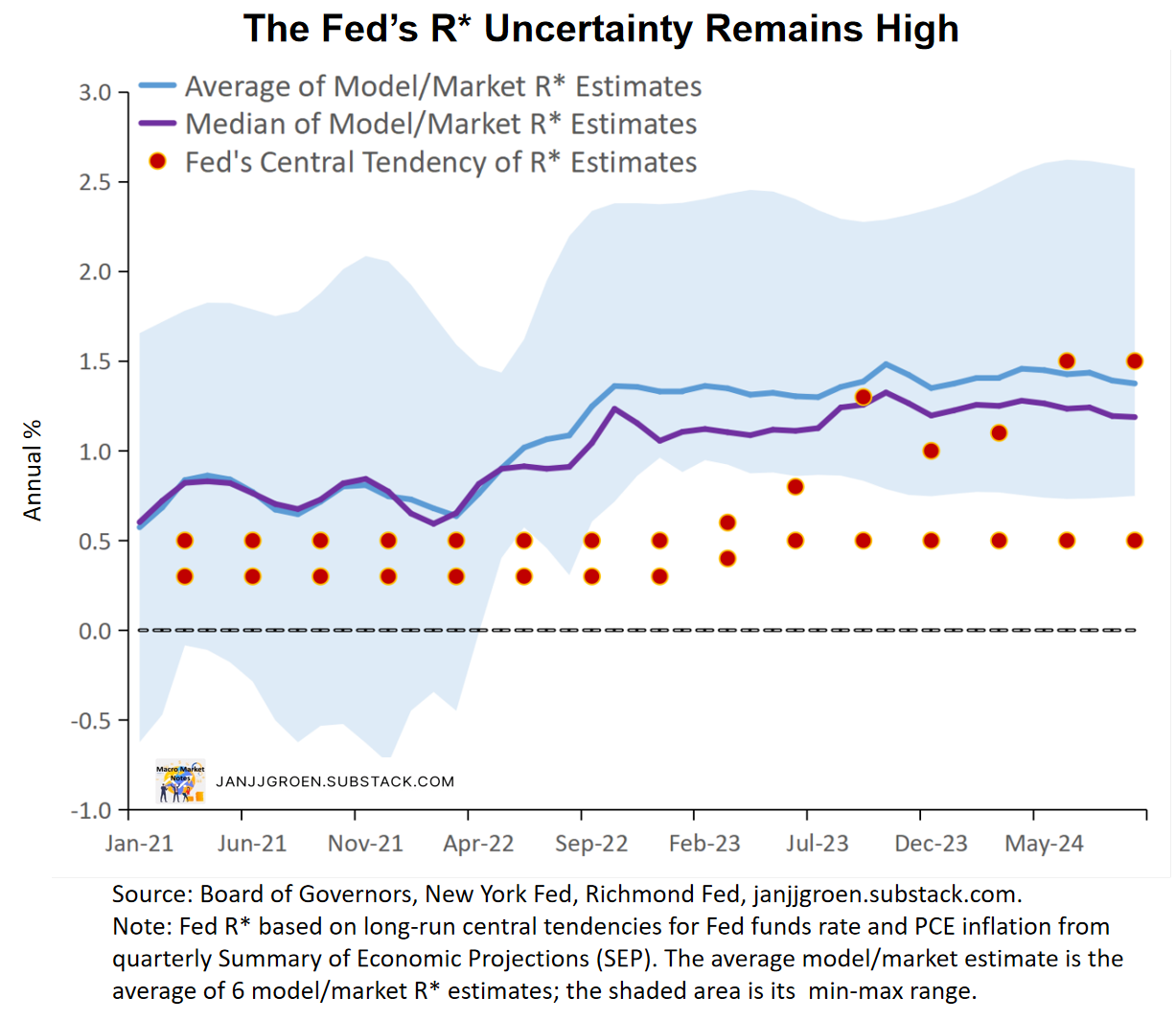

The Fed’s quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) provides a clue about the range of views within the FOMC on R*, using the central tendency for the longer run Fed funds rate and PCE inflation, respectively. The chart above suggests that compared to March the distribution of FOMC members’ own assessment of the neutral real rate did not change materially, with the median barely changing from 0.8% previously to 0.9% now. The Fed’s R* uncertainty remains high, with some FOMC members’ estimates converging towards to those from models and market data.

The chart above contrasts my surveys-based one-year real rate relative to the average of model- and market-implied R* estimates with a proxy of the Fed’s view on this real rate gap using information from its own SEP. This chart suggests that since the March FOMC policy stance expectations from “Main Street” and markets have been in line with the Fed’s own assessment of the restrictiveness of its stance over the year. This partly reflects, however, more disagreement amongst FOMC members since March with regards to the degree of restrictiveness of their policy stance (given the widening of the red dots in June and September compared to March in the above chart).

Looking Beyond Today

The 25bps vs 50bps discussion these past few weeks has been somewhat silly IMHO. What really matters for the economy is how much easing we'll get in TOTALITY between now and the end of 2025. To get a good sense of that you need to have a view on how far the Fed was "behind the curve" before today.

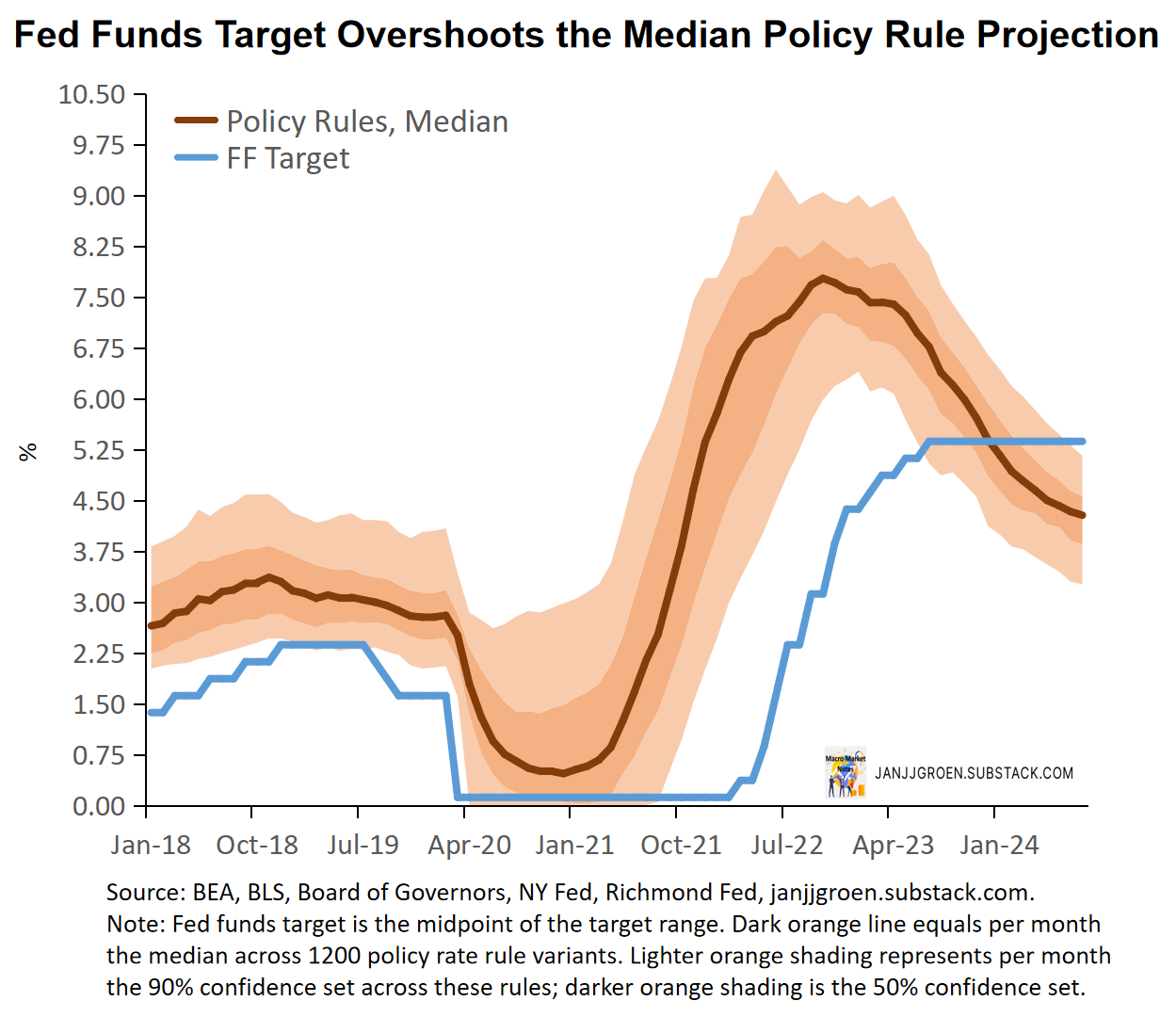

There are wildly different views on this amongst commentators and analysts. A good way to cross check those views is to look at rate prescriptions that result from policy rate rules that relate the Fed funds rate to views about how much inflation deviates from 2% as well as views on whether unemployment rates are "too low" or "too high". Of course, these policy rate rules can differ in their rate prescriptions, owing to

Different preferences to stabilize inflation vs stabilizing the unemployment rate.

What inflation measure you use: current inflation or more forward-looking measures.

Different long-run assumptions, in particular the neutral Fed funds rate level and the long-run unemployment rate.

How (im-)patient central bankers are in pushing the Fed funds rate to its "appropriate" level.

By running the data through a variety of policy rate rule variants that differ along the lines outlined above and aggregating over the range of rate prescriptions,1 you can get a pretty robust sense of where the data suggests the Fed funds rate should be as of now. The chart above suggests that based on the median across a whole bunch of policy rate rule variants the Fed funds target rate was about 100 basis points too high heading into September.

A 100-basis point overshoot was hardly an insurmountable difference going into the September FOMC meeting. And with today’s rate decision and the updated 2024 SEP policy rate projection, it seems with likely two further 25bps over the remainder of 2024 the Fed will enter 2025 with a Fed funds rate level that’s better realigned with underlying economic trends. Chair Powell confirmed this view during the post-meeting press conference, labeling today’s move as part of a “recalibration move”.

The above policy rate rule exercise can also be used to interpret the nature of the easing path beyond 2024 as outlined by the updated SEP policy projections. To operationalize that I assume three, somewhat simplistic, possible trajectories for inflation and the unemployment rate for the rest of 2024 and 2025:

Moderate Growth: The unemployment rate settles above 4% (in line with the SEP) by end-2024 and then remains constant, whereas the inflation measures in the rules are assumed to remain around current levels for 2024 and then gradually ease a total 50bps by end-2025.

Recession: Unemployment rates continue to rise between September and June by a total of 100bps, and then remains constant for H2 2025. The inflation measures are assumed to have declined throughout the projection period by a total of 55bps by end-2025.

Elevated Inflation: The unemployment rate remains constant in Q4 2024, and then gradually declines in 2025 by a total of 30bps by end-2025. The inflation measures are assumed to remain broadly constant in Q4 2024 and then gradually accelerate throughout 2025 pushing the end-2025 inflation rates 25bps higher compared to end-2024.

Chair Powell multiple times typified at the press conference the U.S. outlook as that of an economy that is gradually slowing towards trend growth and 2%, with dialing down policy restrictiveness as necessary in order to get the Fed out of the way of this normalization process. Using the three above-described potential projection paths, you can build a scenario for inflation and unemployment for the year ahead that is in line with Powell’s view: a weighted average of inflation and unemployment rate paths that allocates

65% probability to the Moderate Growth projections,

25% probability to the Recession projections,

as well as a 10% probability to the Elevated Inflation paths.

By pushing the thus weighted inflation and unemployment rate paths through the range of policy rate rules for 2024-2025, one can quantify how the easing cycle could evolve in 2025 based on the signaling by the Fed today.

The chart above shows the result of this exercise. By end-2024 the policy rule-implied Fed funds target (orange line) gradually reaches a midpoint close to a 4.25%-4.50% range, suggesting two more 25bps cuts this year, and by end-2025 this rate reaches a level consistent with a 3.25%-3.50% Fed funds target range, both of which are in line with the SEP, where it hits the potential neutral rate range.2 The chart also depicts the potential Fed funds rate path under the Recession projection (purple line), with the Fed funds rate hitting 2.4% by end-2025. The more aggressive market pricing of future Fed fund rate moves therefore implies a more downbeat market view that the economy already is or soon will be in a recession.

What is notable about the scenario-based policy rate projections in the chart above is that by March the Fed would already have achieved 50% of the implied 100bps easing for 2025. This makes sense, as there’s a wide disagreement within the FOMC about where the neutral Fed funds rate level actually is (2.5% vs 3.5% as per the SEP) and by March the policy rule-implied rate would have dropped below 4%. So, you should expect the Fed to stay on hold for several meetings at a time after the March FOMC meeting, as it feels its way around and internally discusses where the appropriate neutral rate level likely will be.

Today’s rate decision was a surprise to many, including myself, but the Fed made it clear it was merely a move to get a head start to better realign the Fed funds rate with the underlying trends of easing inflation and labor market cooling. Between today and the end of Q1 one should expect more moderate cuts of 25bps at each of the upcoming meetings. The next milestone will be the March FOMC meeting, after which, barring the arrival of a recession, the Fed will likely take a break from the rate cutting cycle. One should expect at most only a handful of correction rate cuts between Q1 and end-2025. Expect FOMC’s internal neutral rate uncertainty to make the rate outlook murkier beyond Q1.

Box: Monetary Policy Rules

While central banks never really set policy rates in an automated manner meeting to meeting, since Taylor (1993) economists have been successful in quantifying more medium-term trends in central banks’ policy rate setting behavior by means of policy rate rules. In these rules the central bank policy rate is described by a linear combination of an inflation gap (inflation deviation from an inflation target), an output gap (output deviation from potential) and an assumed neutral rate. By invoking Okun’s Law one can substitute the output gap with an unemployment gap (Output Gap = 2xUnemployment Gap, Unemployment Gap = Unemployment Rate - Long Run Unemployment Rate). This brings it more in line with the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

By choosing different parameter values for the inflation and unemployment gaps, the rate setting within these rules can be geared towards more inflation stabilization or towards more employment maximization. The table above shows the different parameter combinations I use in this post, ranging from balanced between inflation and employment (the “Taylor Rule”), inflation hawkish (no or little emphasis on unemployment) and unemployment dovish (reacting increasingly stronger to above trend unemployment rates). This is useful as the literature has shown that since the 1950s the Fed has been shifting several times between these differing tendencies in policy rate setting.

Furthermore, different assumptions regarding the neutral rate and the long-run unemployment rate can affect how the policy rate is set in these rules. To operationalize that I use a range of different assumptions. For the neutral rate I use the upper- and lower bounds of the central tendency for the long-run Fed funds rate from the SEPs as well as the nominal neutral rate implied by 2% plus either the average and median across a range of market- and model-implied R* estimates, as I’ve used in the real rate chart discussed earlier in this post. In case of the long-run unemployment rate assumptions I use the upper- and lower bounds of the central tendency for the long-run unemployment rate from the SEPs.

I also different inflation measures: year/year core PCE inflation (backward looking), the survey-based year-ahead PCE inflation expectations discussed earlier in this post, and the 12-month median PCE inflation measure (Detmeister (2012) indicates that such a trimmed mean inflation measure provides a decent description of inflation trends over the near-term).

Finally, the table above also shows I allow for rate inertia, i.e., central bankers can be very patient or impatient in setting actual policy rates in line with their views on inflation and unemployment. To do that I set different values for the inertia parameters: 0, 0.50, 0.55, …, 0.85, 0.90, which suggests half-lives of deviations between actual and target rates of 0 months, 1 month, 1.5 month up to 6 months. Note also that the target rate in the rules is not allowed to become negative: based on my 15 years’ experience as a Fed economist it’s clear to me that the Fed has an absolute aversion in setting negative policy rates, even when conditions are really dire (unlike the Bank of Japan or the ECB).

The different combination of parameter values and long-run assumptions yields 1200 policy rules variants. By running the data through these 1200 rules and aggregate over these, you end up with a policy rate description that takes into account potential shifts over time in the preferences and patience of central bank policy makers.

The Box at the end of this post provides more detail about the different policy rate rule variants that are used in this exercise.

The gray lines in the chart are the min/max range of neutral rates estimates from 2% + the average and median R * estimates used in the real rates chart above as well as the bounds of the central tendency for the long-run Fed funds rates from the SEPs.