Oct CPI & Retail Sales, Jobless Claims Trends and Fed Speak

Core inflation was firm in October; real retail sales remained strong going into Q4. Claims eased rapidly suggesting a rebounding labor market this month.

This note reviews trends from the most notable data releases this week: the October CPI and retail sales reports as well as the weekly jobless claims data.

Key takeaways:

Core CPI inflation was firm in October and trimmed mean CPI measures suggest that in terms of underlying PCE inflation disinflationary trends likely have bottomed out for now.

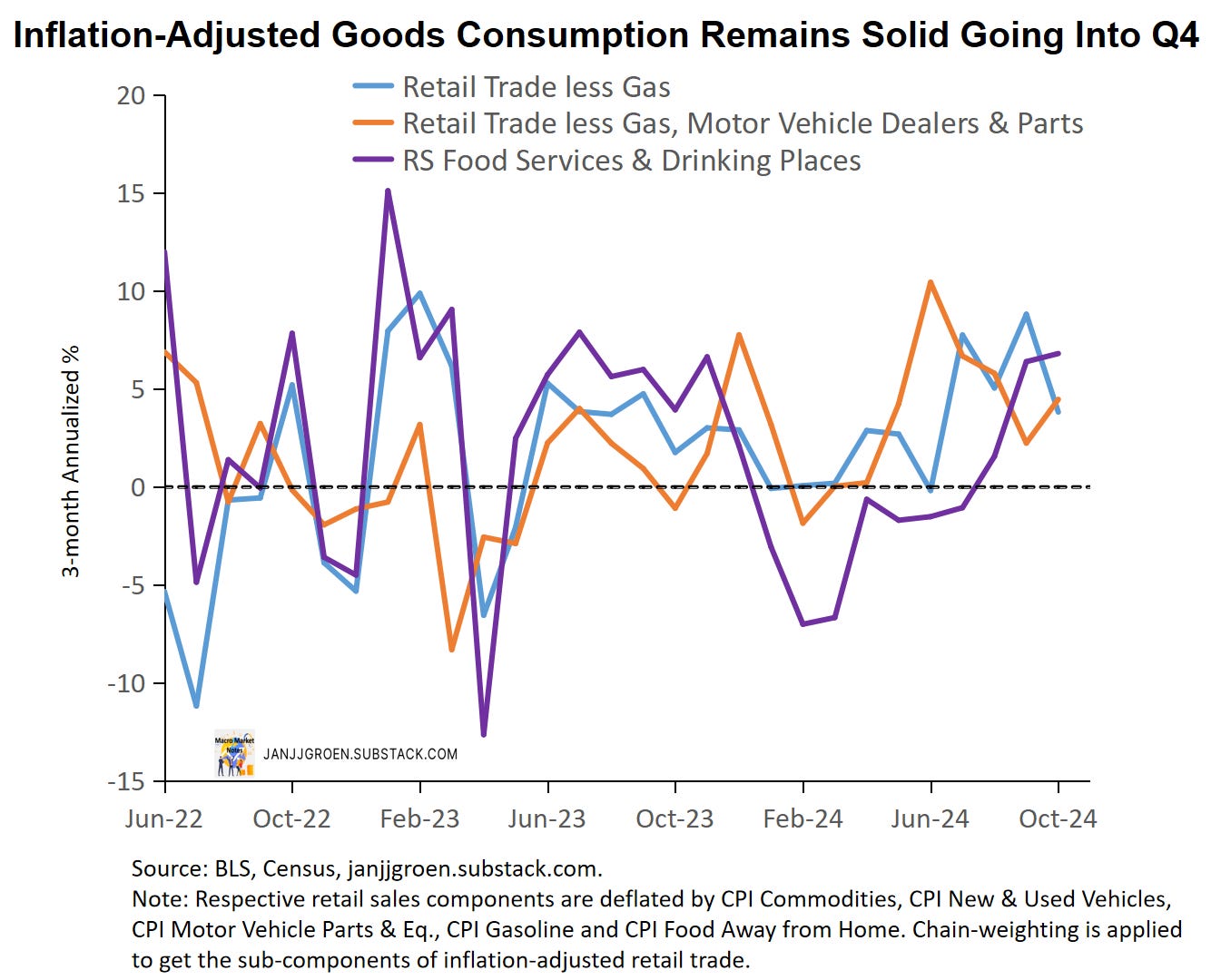

Inflation-adjusted retail sales were solid both for goods and bar/restaurant spending, suggesting Q4 real consumption growth likely will not fade much compared to Q3.

November jobless claims data, for now, suggest that at worst the November unemployment rate will remain similar to October and might ease slightly.

Fed speak emphasized that the Fed is no hurry to cut rates given strong economic growth, a solid labor market and “bumpiness” in the inflation data. A December rate cut is still the most likely outcome but that will possibly be the last one for a while.

October CPI: Approaching the Bottom?

The topline numbers of the October CPI report came broadly in line with consensus expectations. Headline CPI increased 0.2% over the month in October, similar to September, whereas core CPI inflation was up 0.3% m/m (three-digits: +0.280% compared to +0.312% in September).

To get a feel of real underlying CPI inflation, one can look at the Cleveland Fed's trimmed mean CPI measures, which cast away excess volatile elements by either taking the median (price change of the CPI component at the 50th percentile across all price changes) or a 16% trimmed mean (weighted average of price changes once both the top 8th percentile and lowest 8th percentile of price changes are deleted). The Median CPI inflation measure eased slightly from +0.34% month/month to +0.30% in October, and the 16% Trimmed Mean CPI inflation measure similarly eased over the month: +0.27% month/month vs. +0.30% in September. So, the trimmed mean inflation measures (a.k.a. underlying inflation) appeared slightly less sticky over the month than was implied by core CPI inflation.

As usual a big driver behind CPI inflation dynamics remained the CPI Rent of Shelter component (OER+Rent), which increased notably in October relative to September: from +0.2% month/month to 0.4%. CPI OER inflation has been volatile across regions during the summer, with unusual strong CPI OER in the Northeast in May and weakness in June in the West. Between September and October, however, all four Census regions showed a pickup in the month/month OER inflation rate.

On an annual basis there’s less clearcut evidence for the highly anticipated downtrend in the most dominant component of CPI, CPI OER. Year/year OER inflation rates remained stable well above pre-COVID levels in October in the Midwest, Northeast and South, whereas year/year rates in the West were gradually easing (chart above).

Median CPI inflation in the chart above is still overshooting the Fed's 2% inflation target over a six-month period, but it eased nonetheless and the six-month averaged 16% Trimmed Mean CPI inflation measure has closed in on the target.

When using the strong correlation between the CPI and PCE trimmed mean inflation series, statistical nowcasts of Median and Trimmed Mean PCE inflation (due later this month) suggest near-term underlying PCE inflation trend measures will likely have ticked up in October but remained below 2.5% (diamonds in the chart above). So, the nowcasts of underlying PCE inflation dynamics seem to signal that, for now, the disinflation trend has bottomed out.

October Retail Sales: Continued Strength into Q4

Retail trade (i.e. retail sales pertaining to goods) went up 0.4% over the month in October, after it increased 0.8% month/month in September (upwardly revised from 0.3%). As always, it's crucial to remember to not take these figures at face value without looking under the hood:

Retail sales measures spending on goods as well as bar/restaurants spending. Thus, it really mostly measures goods consumption which is a relatively small slice of the monthly consumption basket, as about 2/3 of U.S. consumption expenditures relates to services.

Retail sales data does not correct for changes in prices, which for goods in particular can make a big impact: core goods prices in the October CPI report went up 0.04% month/month. As such weaker retail sales growth could merely reflect more the pace of price increases while retail sales volumes were solid.

Merely deflating retail sales with CPI or core CPI overlooks the predominantly goods-focused nature of retail spending.

Dissecting retail trade data into subcomponents and aligning them with corresponding CPI subcomponents provides a more accurate assessment. Firstly, when it comes to retail trade data (that is, retail sales minus nominal bar and restaurant spending) I use the CPI Commodities, CPI Gasoline, CPI New & Used Vehicles and CPI Motor Vehicle Parts & Equipment indices to inflation adjust over retail trade as well as components related to sales at gasoline stations and motor vehicle dealers & parts. In case of bar and restaurant spending I deflate that component by means of the CPI Food Away from Home index.

Furthermore, I apply chain-weighting based on the Fisher index approach using current period and previous period prices and quantities of retail trade and the gas and motor vehicle components to parse out the impact of the latter two volatile components. This approach allows for time-varying weights, as prices and quantities change from period to period and consumers substitute between the different spending categories. It is the same methodology used by the BEA to compute real consumption and GDP.

Core goods spending remained strong in inflation-adjusted terms on a three-month basis, as is evident from the chart above. Despite declining over the month, real core goods spending excluding motor vehicles picked up somewhat on a three-month basis in October (orange line in the chart above), thanks in part to whopping 22.2% annualized month/month increases in September.

After the sharp acceleration in September, bar and restaurant spending remains strong in inflation-adjusted terms at a 6.8% three-month AR (purple line in the chart above), the highest since November 2023. Strong real bar and restaurant spending does indicate improving consumer confidence to spend more broadly. In summary, the inflation-adjusted October retail sales seem to suggest that real consumption expenditures for Q4 will hardly slowdown compared to Q3.

This Week’s Initial Jobless Claims Trends

After a slight pickup in initial claims for the week ending November 2nd, data for the week ending November 9th showed somewhat of a reversal of the preceding week’s move at 217,000 persons versus 221,000 previously.

When I focus on non-seasonally adjusted data and compare today’s data with data from previous years in the same week it suggests that so far in November the initial claims data is fairly similar to trends seen in 2018 and 2023 (chart above). So, initial claims remain stable at historically subdued levels.

In terms of the unemployment outlook, initial claims are usually considered as a high frequency, real-time indicator of layoffs. What is relevant in that context is whether the layoff rate as implied by initial claims is significantly high or low to put substantial upward or downward pressure on the unemployment rate. To assess this, I laid out earlier a methodology to determine a benchmark rate for initial claims for the current month that equals the maximum number of initial claimants that will keep the unemployment rate constant relative to the previous month. If current initial claims rise above this claims benchmark rate, initial claims could potentially start to add to the unemployment rate.

The chart above compares (seasonally adjusted) initial jobless claims and its four-week moving average with the claims benchmark rate based entirely on BLS data (orange line) as well as a claims benchmark rate that instead incorporates the CBO’s more aggressive population projections for 2023 and 2024 (purple line). The more aggressive population growth projections clearly have lowered the benchmark rate for claims this year (orange vs. purple lines in the chart above), where especially during the May-July period a combination of increased labor supply and slowing net hiring by firms meant that the U.S. labor market over the summer reached its limits in terms of its capacity to recycle initial jobless claimants back into new jobs.

Throughout August and September, initial claims eased below their claims benchmark rates, but spiked well above those in early October owing to hurricane impacts in the Southern states. Since the second half of October, initial claims moved down again notably and well below levels beyond which they’d would put upward pressure on the unemployment rate.

Furthermore, when we look at continued claims (jobless claimants that use benefits beyond 1 week) as a percentage of insured employment in the chart above, we notice that up to now they remain essentially in line with what we’ve seen last year. So, the high frequency labor market data for November so far suggests that at worst the unemployment rate in November remains in the 4.1%-4.2% range with a reasonable likelihood that it could end up in the 4%-4.1% range.

Fed Speak

We had a flurry of Fed officials making public remarks this week, including Chair Powell. Bottom line of these remarks is that the Fed views economic performance as really strong, driven by strong disposable income growth pushing up consumption growth, and the labor market solid, likely reflecting in Fed President Collins’ words “full employment conditions“. Inflation likely will be bumpy but eventually will return, with the Fed put a lot of faith in declining housing services inflation to do this job. With the economy expanding at its current pace despite relatively high policy rates, more and more Fed officials are now voicing an expectation of a higher neutral Fed funds rate level. All in all, based on this week’s Fed speak the Fed views there’s still a case to ease policy rates further but continued economic strength means they’re in “no hurry to cut rates” (Chair Powell’s words) and likely will end up at a higher trough rate than previously expected.

Does this mean that a rate cut at the December FOMC meeting is off the table? I don’t think so. Chair Powell made it clear right after the September FOMC meeting that rate cuts were meant to recalibrate the Fed funds rate and make it more aligned with underlying economic trends. As I argued in my November FOMC preview, 25 bps rate cuts at the November and December meetings would essentially bring about this alignment (e.g. we see that when we push the data through a wide range of policy rules).

Additionally, and something I raised after the November FOMC meeting, increasingly higher bond yields since the September FOMC meeting (chart above) is becoming a worry for some Fed officials:

Since the FOMC began cutting the fed funds target in September, the 10-year Treasury yield has actually risen by roughly three-quarters of a percentage point. Some of that rise reflects expectations for a higher path of policy rates. And, so far, higher equity valuations and tighter credit spreads have offset the tightening in financial conditions from higher Treasury yields. But a substantial fraction of the increase in long-term yields appears to reflect a rise in term premiums. Term premiums compensate investors for bearing the risk of future interest rate fluctuations. Higher term premiums can tighten financial conditions for any given setting of monetary policy and thereby slow the economy more than the FOMC intends. If term premiums continue to rise, the FOMC may need less restrictive policy, all else equal, to accomplish its goals.

Logan, L, “Navigating in shallow waters: Monetary policy strategy in a better-balanced economy“, November 13, 2024.

If higher term premia continue to constrain financial conditions going into the December FOMC, this would make a 25bps rate cut more palatable for a lot of Fed officials despite the likely bottoming out of disinflationary trends.

Beyond the December FOMC meeting it is becoming more and more likely, in my view, that we are not going to get additional rate cuts for quite a while. And this not so much by the Fed’s design but more due to emerging data trends that suggest elevated inflation will become more of a policy concern, even abstracting from policy initiatives that will come out of a new White House. I see a number of Fed officials (e.g., Fed President Kashkari’s Bloomberg TV interview this week) as well as Wall Street commentators making the case that slower nominal wage growth and improved productivity are lessening upward pressure on prices. I have my doubts about that.

Firstly, I showed after the Q3 productivity report release that labor productivity is still below trend but is close to catching up with it soon (chart above), which will mean temporary productivity tailwinds for inflation are about to fade when we get into 2025 and certainly are not a permanent feature. Furthermore, private sector ECI wage growth slowed but remains above 2% inflation pace, driven by above trend growth of workers' share of business revenues.

Finally, using the Q3 productivity and labor share numbers indicates that recent nominal wage growth runs well above the 2% PCE inflation pace and probably more in line with 2.5%-3% PCE inflation over the medium term (chart above). That will continue to pose upside risks to services inflation going into 2025.

Thus, even without potentially inflationary policy initiatives from a new administration in DC, data trends point to inflation stickiness coming to the forefront next year.