Wages and Inflation Expectations - November 2023 Update

Wage growth continues to overshoot the pace consistent with the Fed's inflation target, as inflation expectations seem to gain ground above 3%.

A few months ago, I laid out a framework that can be used to interpret wage growth trends relative to inflation expectations and the Fed’s inflation target. The resulting W* measure reflects a trend wage growth rate where demand and supply in the labor market are in balance given an inflation outlook. It is equal to either the 2% inflation target or year-ahead inflation expectations plus a trend labor productivity growth estimate as well as a trend labor share growth estimate. The latter component corrects my original W* for long-run shifts in workers’ compensation as a share of non-farm business sector revenues (a.k.a. the labor share).

With new wage data for October, labor productivity and labor share data for Q3 and updates of inflation expectations data for October and November, this note will update the above-mentioned wage growth framework.

Key takeaways:

Since July, “Main Street” inflation expectations have been stuck at a 3+% PCE rate and appear to start moderately rise again since October.

Consequently, trend wage growth based on these inflation expectations (W*) is also gaining momentum, suggesting that there will be less wage disinflation in the pipeline than previously expected.

W* is consistent with about 3.5% PCE inflation, above the Fed’s 2% inflation target. So, any actual further wage growth easing in line with this measure will keep wage growth at an above-target pace.

Corrected for expected inflation, trend productivity growth and trend labor share growth, wage growth still remains a boost for households’ real incomes and spending.

Inflation Expectations

As familiar to some readers, one of the W* trend wage growth measures I use builds on inflation expectation surveys drawn from “Main Street”, i.e., five inflation expectations samples from households and firms. Since the last note, three out of these surveys got updated with observations for October and one survey providing expectations for November (the preliminary University of Michigan Survey results on Nov. 10).

The preliminary median one-year ahead inflation expectations for November from the University of Michigan Consumer Survey ticked up again (from 4.2% in Oct. to 4.4% for early Nov.). As explained in my original W* note, these inflation survey measures are aggregated by means of a single dynamic common factor that depends on its own lag using the approach of Banbura and Modugno (JAE, 2014).

The updated individual expectations series are plotted in the chart below alongside the updated, estimated common factor across these series. After scaling the factor in year-on-year PCE inflation terms, inflation expectations got slightly revised up for October from previously 3.45% to 3.50%. The preliminary estimate for November currently suggests inflation expectations might be around 3.60%. It seems “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations have been stuck at 3+% levels since July and might have gained some momentum in October and November.

Trend Labor Productivity and Labor Share Growth Rates

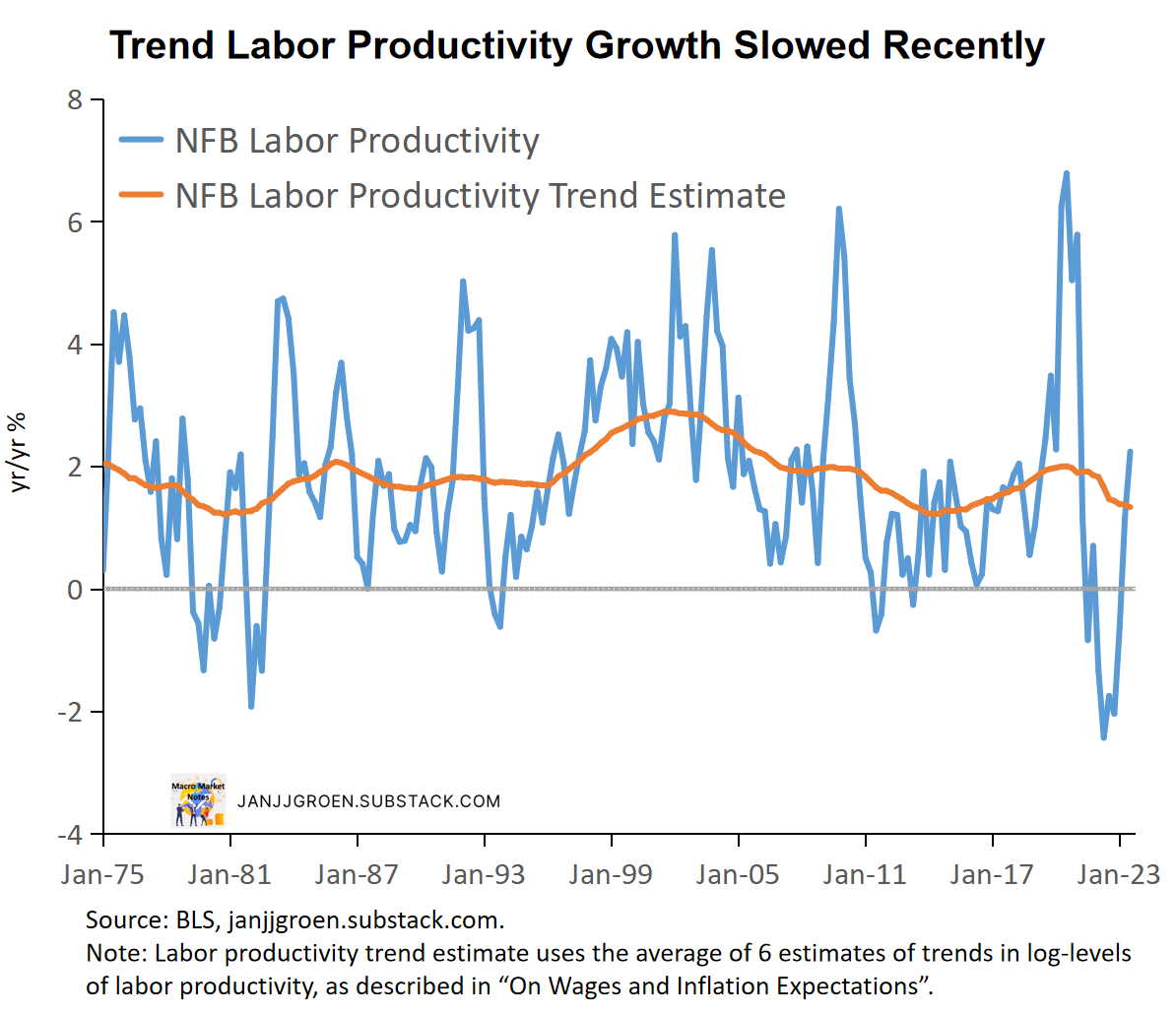

With the release of the BLS's "Productivity and Costs" report for Q3 we again, like in Q2, had an acceleration of labor productivity growth. After updating my own estimate of trend labor productivity in the nonfarm business sector, labor productivity remains below-trend so catch-up dynamics will likely keep growth rates temporarily elevated. Nonetheless, the year/year trend labor productivity growth rate for Q3 remains subdued historically at around 1.3% year/year, as is shown in the chart below.

The labor share equals the ratio of total workers compensation relative to nominal output of businesses. As for labor productivity, I approximate the labor share trend by taking the average of six trend estimation methods applied to the actual labor share data, as outlined in my original W* note.

The chart below shows this labor share trend estimate. Leading up and right after the GFC the trend labor share declined sharply, and then started to rise again from 2015. More recently, however, the labor share trend has drifted down again. This likely means that the Fed needs to see even lower wage growth levels than originally estimated to have these rates in line with its inflation target.

Wage Growth

To recap, to assess wage growth trends I combine the following three ingredients I discussed in the previous sections, i.e.,

The trend productivity growth estimate described earlier (assuming a Q4 trend labor productivity level based on the trend labor productivity change over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

A similar estimate of trend labor share growth (assuming a Q4 trend labor share level based on the trend labor share change over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

And, either the year-ahead inflation expectation proxy based on the common factor from surveys or the 2% inflation target.

This will result in two alternative trend wage (W*) measures, and I compare these in the chart below with Atlanta Fed wage tracker wage series that measure average hourly wages of workers that are robust to compositional changes over the month. In addition, I use in the chart a composition-adjusted average hourly earnings (AHE) wage series for production and non-supervisory workers as constructed at the Atlanta Fed, which can be found here.

As in previous months, the chart above continues to suggest that wage growth overshot the expectations-based W* metric, suggesting positive expected real wage growth throughout the first three quarters of 2023 and into Q4. Note, though, that,

Actual wage growth and the expectations-based W* measure still outpace the trend wage growth rate that is consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target, currently in line with about 3.5% PCE inflation rate.

With the declining trend in the labor share incorporated into the W* measure, the Fed needs to see year/year wage growth in the 2.5%-3% range for it to be consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium term.

An important wage pressure gauge for the Fed is the quarterly ‘Employment Cost Index’ (ECI), another wage measure that corrects for compositional changes, of which we got the Q3 release last week (Oct. 31). The all-important ECI index for wages and salaries of private sector essentially remained unchanged at 4.5% year/year in Q3. In my post-Q3 Productivity Report post, I used the W* framework to quantify what drove ECI wage growth to be at such an above-inflation target pace, essentially using a quarterly version of the green W* line (reflecting trend wage growth in line with 2% PCE inflation) in the chart above.

The chart below depicts the result of this ECI private wage growth gap decomposition but now with today’s update on inflation expectations incorporated for Q4. It shows that for Q4 we can expect to get more upward pressure on the ECI private wage measure from above-target “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations. Going into Q4, and possibly beyond, we should not expect to get a lot more easing in the ECI private wage growth measure, which is a worry for the Fed.

Implications

The data on “Main Street” inflation expectations do suggest that, for now, the downward adjustment in expectations is behind us and have moderately risen again over the past two months. Consequently, the expected degree of easing of wage growth has lessened since September.

The positive expected real wage growth rate seen throughout 2023 owing to a strong labor market, has been a boost of expected real wage incomes of household. This has kept consumption at robust levels (see also my recent PCE note). In turn this has kept inflation expectations at above target levels and, thus, the rate of trend wage growth.

This interplay between labor market strength and solid consumption spending remains a major driver for the Fed’s behavior going into 2024. The Fed needs to see the economy to start expanding at a below trend rate sooner rather than later, in order to bring down “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations more in line with 2% inflation, and thus also wage and spending growth rates. The longer this takes the more above-target inflation expectations get entrenched in firms’ and households’ behaviors.