Dec FOMC Meeting: Heading for the Exit

The Fed's hiking cycle is done and discussions within the FOMC from hereon will focus on the timing of rate cuts, likely not earlier than mid-2024.

Since the July FOMC meeting the immediate rate decisions at subsequent meetings have been ones of no change in the Fed funds rate target range, and today was no different. Chair Powell’s remarks at the post-meeting press conference signaled that we have reached peak policy restrictiveness and the main concern for the Committee is now to determine the timing of cuts. In other words, the Fed will use its deliberations in Q1 to quantify the “long” in “high for long”. Meanwhile, the Fed’s communications will attempt to keep financial markets tamed and to not let it cause an impetuous easing in financial conditions.

Key takeaways:

The FOMC decided to keep the Fed funds target rate unchanged at 5.25%-5.50%, and clearly signaled that the hiking cycle has ended.

Underlying core services inflation and near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations are showing tentative signs of a pick-up in downward momentum.

On the other hand, the labor market and consumption spending remains relatively strong.

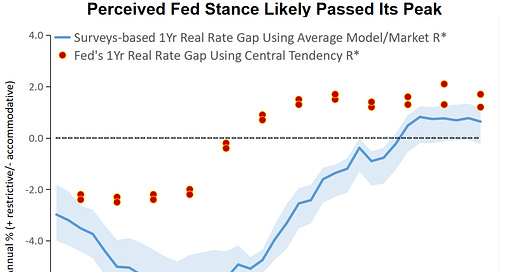

Since the September FOMC meeting, however, the perceived monetary policy stance has become less restrictive and undershoots the Fed’s own assessment of its stance.

Given some easing in the expected year-ahead real rate path and solid real economic activity levels, the FOMC will likely be patient in assessing more progress in inflation data and inflation expectations trends before deciding to cut policy rates.

Fed funds rate cuts will likely not begin until mid-2024. There is, however, a risk cuts will already commence in 2024Q1 owing to a combination of the Fed overestimating the restrictiveness of its current policy rate level and possible continued rapid disinflation pace in the spot inflation data over the next two to three months.

Easing Inflationary Pressures and Solid Labor Market

As core goods inflation largely has been coming down owing to normalizing supply side constraints and external factors, and housing services inflation is expected to ease also given weak new rents, the Fed has emphasized developments in core services excl. housing inflation. The latter component of core inflation is mainly driven by:

Labor costs, as most of the categories in core services excl. housing inflation are labor-intensive in nature.

Consumption expenditures.

It is therefore not surprising that the Fed over the past six months has in terms of its interest rate setting policy put less emphasis on spot inflation data and more so on consumption and labor market data.

While momentum in PCE core services excl. housing inflation has been sticky around a 4% m/m annual rate for most of the time since 2021, the October Personal Income & Outlays report did show tentative signs that this inflation measure could finally break south of this 4% level (chart above). On the other hand, the November CPI report did suggest that the CPI-equivalent of core services excl. housing inflation still exhibits some upside momentum. Now as the chart above makes clear is that the CPI-based “core-of-core” measure has been more volatile than the PCE-based counterpart, reflecting a narrower breadth than in case of the PCE index, so this could explain the recent divergence. Also, some components of the PCE core services excl. housing inflation rate use PPI series as source data, and today’s PPI report suggests that some more easing might be in the pipeline for November. Bottom line is that the Fed, for now, can be tentatively optimistic about the recent trends in “core-of-core” PCE inflation.

Another key factor in the Fed’s assessment of progress on inflation normalization are inflation expectations of firms and households, especially near-term expectations as this impact heavily on wage negotiations, price setting and spending. Research has shown that these types of inflation expectations are the stickiest and often are positively correlated with growth expectations of these same firms and households. Since July I have been monitoring the common trend across near-term inflation expectations from surveys of firms and household from different sources, in order to aggregate these different measures and simultaneously filtering out idiosyncrasies form each of these individual surveys.

Through November this common trend across firms’ and households’ inflation expectations suggested that these inflation expectations stalled over the July-October period at around 3.2% in year/year PCE inflation terms and ticked up somewhat in November. Since then, we got updates from a number of source surveys for my estimate of the common trend in “Main Street” inflation expectations:

The preliminary University of Michigan survey for December, which showed year-ahead inflation expectations plunging from 4.5% in November to 3.1% in December.

The November Survey of Consumer Expectations from the NY Fed that indicated a decline in year-ahead expectation from 3.57% in October to 3.35%.

The Atlanta Fed’s Business Inflation Expectations survey for December pointing to a decline in median 12-month ahead inflation expectations to 2.35% from 2.50%.

When taking on board these new data points, a re-estimation of the common “Main Street” inflation expectations trend now suggests a downward revision to November inflation expectations from 3.45% to 2.99% (chart above), a decline from a revised 3.15% level in October. And with the preliminary estimate for December suggesting another slight decline to 2.95%, we might now see tentative signs that after a mid-year stalling in the easing of “Main Street” inflation expectations this easing could be gaining momentum again.

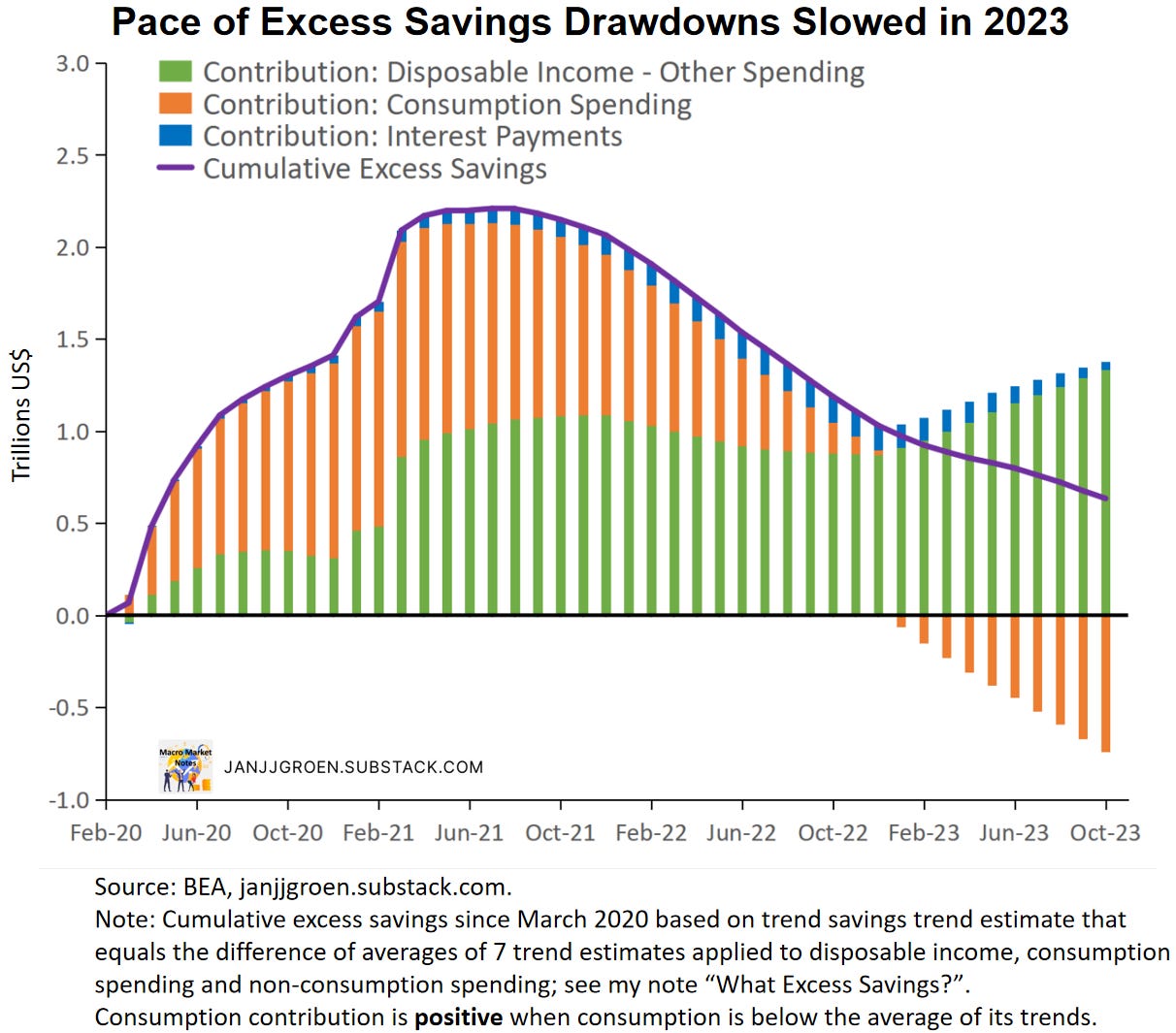

Outside of inflation the economy has been running at a solid pace. Most of the unexpected strength in the U.S. economy came from the consumer. Despite rising credit costs, households were able to keep spending at a healthy rate supported by a still big pile of excess savings (chart above).

Additionally, the labor market remained solid with a slight gain of job growth this fall and this has been another source of elevated consumption spending. Consequently, households’ wage income accelerating again this fall (chart above).

Although the labor market cooled over the summer as hiring by firms, as approximated by the job-finding rate (the likelihood that in a given month a person moves out of unemployment), slowed meaningfully (chart above). However, since the summer this job-finding rate moved up again, suggesting that solid labor market strength will likely continue going into 2024.

Overall, today the Fed saw signs of services inflation that might be on the verge of becoming less sticky and continued consumer and labor market strength.

How Tight Is the Fed’s Policy Stance?

Where does this leave the Fed and its interest rate policy? Based on an earlier analysis I did, I gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is by focusing on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the chart above that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

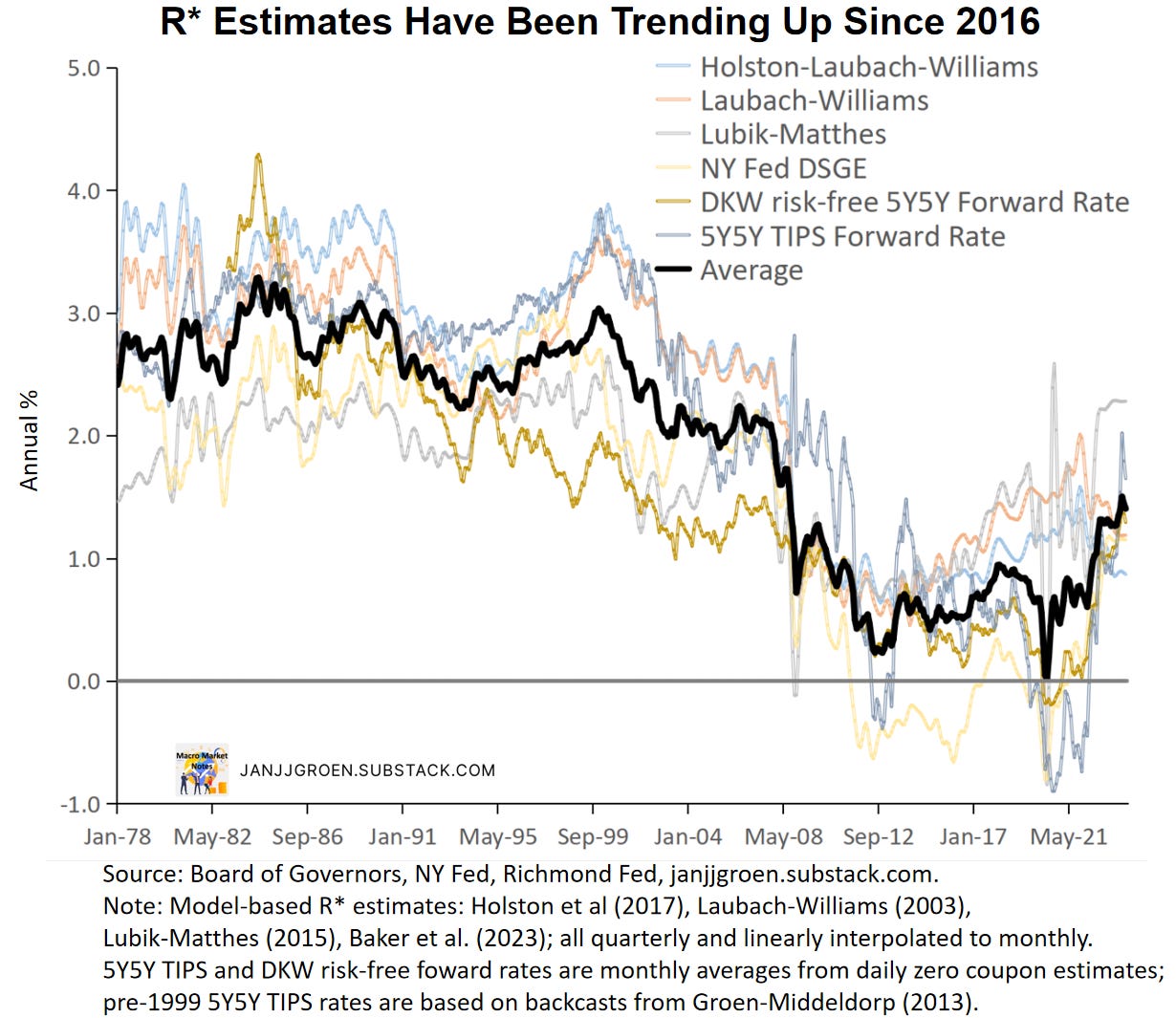

To assess how restrictive these one-year real rates are we do need to know where neutral real rates are heading. The chart above is an update of an earlier chart and shows that after close to a decade of ultra-low neutral real rates, these rates have trended up since 2016. These upward trends accelerated further earlier this year, but they have plateaued more recently with the average across the proxies closing in on a 1.4% level by November, early December.

Judging from Chair Powell’s remarks at today’s post-meeting press conference, the Fed seems now convinced that its rate hikes have pushed its policy stance to a level that is restrictive enough to bring inflation sustainably back on a path towards 2%. The perceived policy stance as depicted by the survey-based one-year real rate in the chart above only became restrictive (by rising beyond neutral real rate levels) after the May FOMC meeting, reaching a potential “choking point” for the economy that was not too different from seen in previous hiking cycles. Since then, the expected restrictiveness of the Fed’s policy stance already peaked at around the September FOMC meeting, after which elevated “Main Street” inflation expectations and R* as well as declining nominal yields have eroded this restrictiveness.

The Fed’s Own View

FOMC members updated their forecasts for inflation, growth the unemployment rate and the Fed funds rate at this meeting. The inflation outlook was modified, especially for 2023 as the unexpectedly fast disinflation seen since the summer undermined the original September 2023 Q4/Q4 core PCE inflation projection of 3.7%, which was today downgraded to 3.2%. The Core PCE inflation for 2024 was also revised down, but only slightly from 2.6% Q4/Q4 in September to 2.4%. The SEP projections for growth and unemployment in 2024 remained broadly unchanged relative to the September FOMC meeting, with growth remaining below trend at 1.4% Q4/Q4 and the unemployment rate rising to 4.1% by Q4. Finally, the Fed funds projection for 2024 suggests now three rate cuts for next year instead of two.

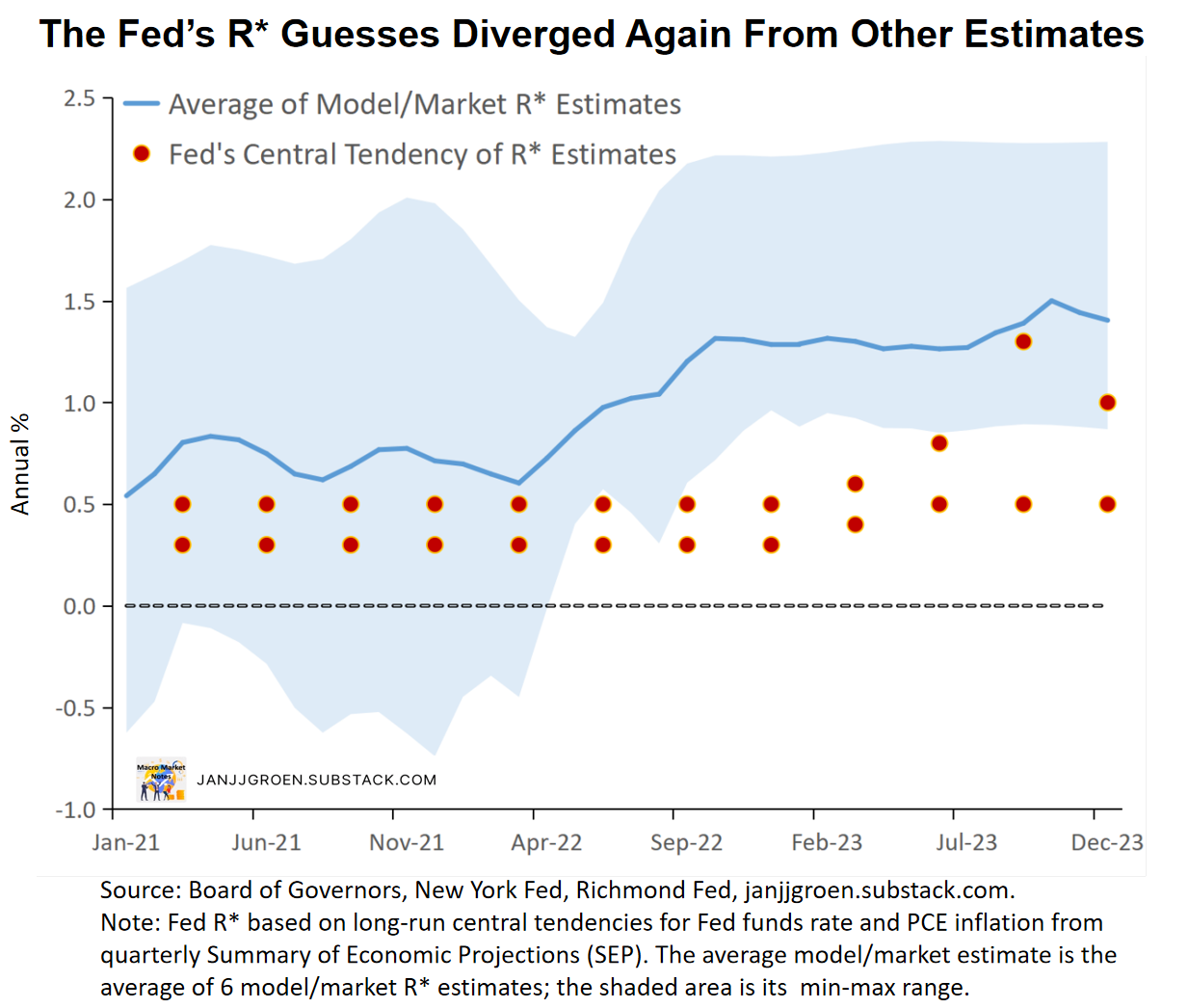

As discussed earlier the range of R* estimates from models and financial markets data suggests that R* shifted up towards a level close to 1.4%. The Fed’s quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) provides a clue about the range of views within the FOMC on R*, using the central tendency for the longer run Fed funds rate and PCE inflation, respectively. The chart above suggests that earlier a number of FOMC members have been upgrading their own assessment of the neutral real rate, in line with markets-data and model implied proxies. However, at the current December meeting FOMC members dialed back their R* guesses and brought them back closer to the range we’ve seen at the start of the year.

This dialing back in the Fed’s assessment of the neutral real policy rate essentially meant that the Fed is now convinced its policy stance has been more restrictive than originally thought back at the September meeting. In the chart above, I contrast my surveys-based one-year real rate relative to the average of model- and market-implied R* estimates with a proxy of the Fed’s view on this real rate gap using information from its SEP. The chart above suggests that compared to expectations on “Main Street” and markets, the Fed continues to overestimate its degree of monetary policy tightening.

Looking Beyond the December FOMC Meeting

Chair Powell made it clear today that the Fed’s policy stance now is “appropriately restrictive” with the Fed funds rate at its peak level for this hiking cycle. He also signaled at the post-meeting press conference that the FOMC already had begun discussing the timing of dialing back the current levels of policy restriction. In itself this does not mean that the Fed is ready to really ease policy in inflation-adjusted terms. It would be “maintenance cuts” that will keep the inflation-adjusted path policy rates from rising beyond current levels, as inflation continues to ease.

The problem currently is that the markets, partly based on erroneous interpretations of public remarks by Fed officials, are interpreting the easing in spot inflation data as a sign that these maintenance cuts are already forthcoming in Q1 of 2024. In reality, Fed officials are utilizing more of a forward-looking view, based on the expected path of inflation for the year ahead. Today’s update of the SEP projections shows this expected path really did not change that much. And while, as discussed above, there are tentative signs of more cooling ahead in underlying inflation trends (especially core services excl. housing inflation) and near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations, perceived year-ahead real rates are actually easing somewhat. In combination with a still robust labor market and consumption spending, this means that the Fed can afford to be patient in determining the start date of maintenance cuts to further assess whether inflation is indeed easing along a medium-term path back to 2%. My modal view, therefore, is that we are not going to see a move toward policy rate cuts before mid-2024.

However, there is a substantial downside risk to this model view. As I laid out earlier, the Fed, compared to perceptions elsewhere in the economy, is overestimating the restrictiveness of its current policy stance, which is supported by a continued unemployment rise in its own 2024 projections. Given that view and a possible continued rapid disinflation pace in the spot inflation data over the next two to three months, there is a risk that the Fed will feel compelled to already start cutting the Fed funds rate in 2024 Q1. With a still strong labor market and elevated wage growth going into 2024 this might actually increase the upside risk to inflation later on in 2024.

In any case the Fed’s communication for now will have its work cut out to contain financial market pricing and not having it induce any premature financial conditions easing that could stoke inflationary pressures later on in the new year.