Rebounding Labor Market and Productivity Data

Labor productivity is catching up with its trend and labor share is downshifting. A rebounding job-finding rate suggests more labor market strength ahead.

Data on revisions of Q3 labor productivity data as well as the November Employment Situation report garnered a lot of attention. Under the hood of these data releases are signs of continued strength in the U.S. economy which will keep the Fed on hold in terms of its policy stance. This note will discuss these signs in more detail.

Key takeaways:

Labor productivity growth accelerated for the second consecutive quarter, but as labor productivity still is below its trend estimate this mainly reflects catch-up dynamics.

The labor share contracted again and remains below its trend estimate, which pushes down on the medium-run wage growth rate consistent with 2% inflation.

Payrolls growth momentum firmed up since the summer and runs well above the breakeven pace needed to keep the unemployment rate constant.

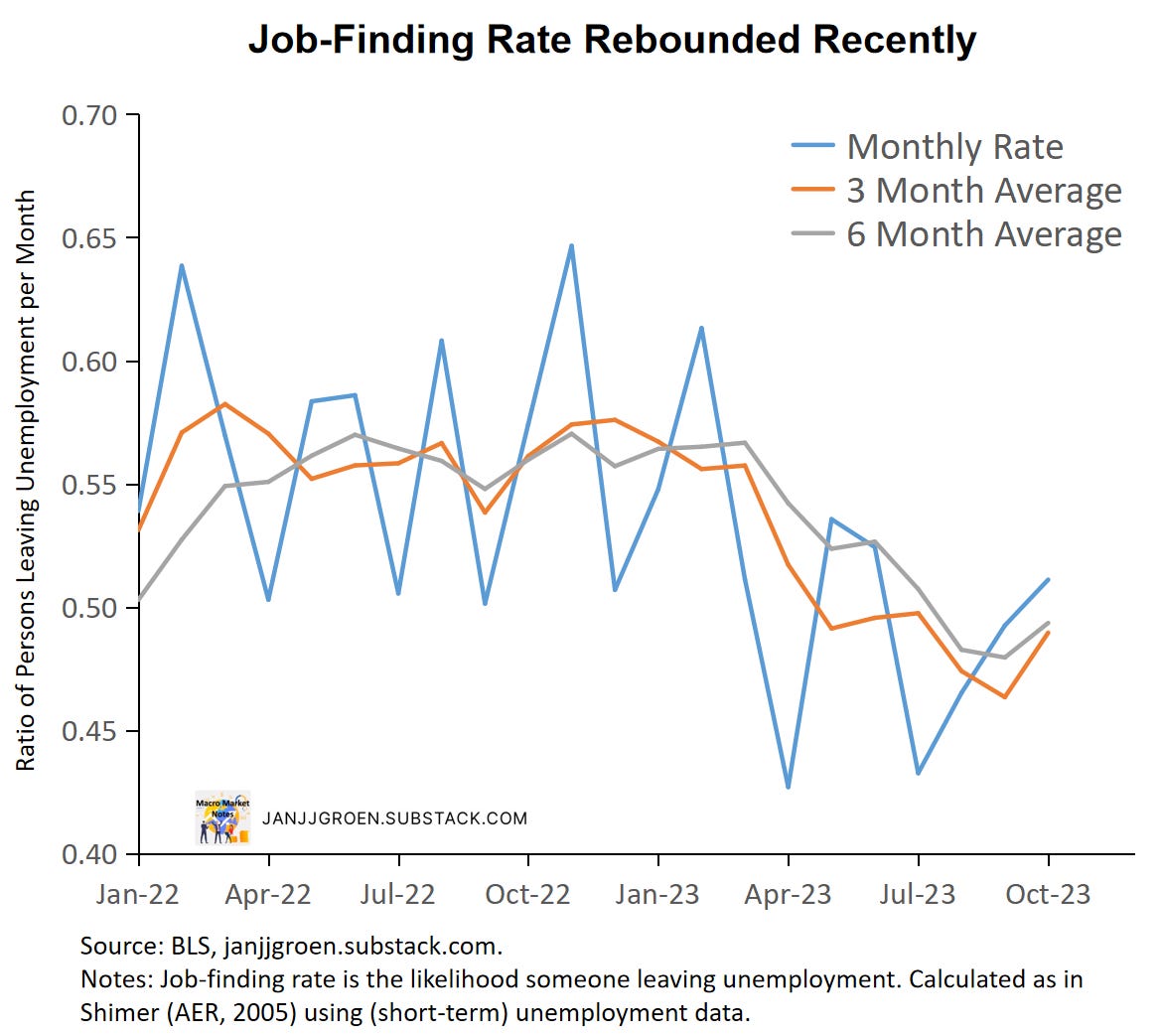

After slowing earlier in the year, the job-finding rate has been on a rebound since the summer, mainly reflecting a recovery in hiring by firms.

Wage growth disinflation appears to lose momentum, with wage growth still outpacing the medium-run rate that is consistent with 2% inflation.

Q3 Productivity & Costs Revisions

Earlier this week the revisions of the BLS’s Q3 “Productivity and Cost” estimates were released. Labor productivity for the non-farm business sector grew 2.4% year/year in Q3 (revised from 2.2% in the preliminary report), after increasing 1.2% in Q2, which contrasts with the seven quarters that preceded Q2 when labor productivity dropped throughout most of that period.

To quantify the underlying longer-term trend of labor productivity, I estimate trend productivity using a number of different purely statistical approaches as outlined here. The average of the estimates from these approaches is my trend labor productivity estimate.

Comparing actual labor productivity with my trend estimate in the chart above suggests that after a long period of declines labor productivity turned a corner in 2023 and started to converge back to trend. The recent above-trend labor productivity growth rate therefore is reflective of catch-up dynamics with actual productivity going back to trend rather than a structural upward shift in labor productivity.

The labor share represents the compensation firms pay their workers as a share of the firms’ revenues. This measure is useful to have alongside labor productivity data, as higher labor productivity in principle should result in higher real wages but the extent to which this happens depends on this labor share - a concept that is largely ignored in current public macro policy debates. In Q3 the labor share for the non-farm business sector contracted 1.4% year/year (revised from -1.1% in the preliminary report), and it has been declining for eight of the ten preceding quarters.

As was the case for labor productivity discussed earlier, I use an average across different purely statistical approaches (outlined here) to pin down the trend labor share - the orange line in the chart above depicts this trend estimate. Throughout 2016-2019 this trend labor share was stable, but it has been on a declining trajectory since 2020. Trend labor share growth in Q3 was -0.7% year/year (revised from the preliminary estimate of -0.6%) compared to an unchanged trend growth rate throughout 2019.

Especially the continued structural decline in the labor share should be a worry from the Fed’s perspective. As I outlined last month, combining trend estimates of labor productivity and the labor share with the Fed’s inflation target suggests over the past 18-24 months that wage growth should slow to the 2.5%-3% range rather than the 3%-3.5% range so frequently cited by Fed officials. Current wage growth rates are far removed from that range.

November Jobs Report: Turning a Corner?

The November jobs report released today (December 8th) suggests the U.S. labor market remained strong across the board. Payrolls were up by 199,000 persons in November, up from a 150,000 increase in the preceding month. Main drivers were both the manufacturing sector (+28k in Nov. from -35k in Oct.) as well as the private services sector (+121k in Nov. from +95k in Oct.).

The unemployment rate dropped 20 basis points to 3.7% in November, as the household employment growth bounced back sharply relative to October: from -348,000 persons in October to +747,000 persons. The labor force participation rate meanwhile increased from 62.7% to 62.8% in November. The labor force participation rate has been stable around 62.8% since August, well above the longer-term trend as estimated, for example, by the CBO.

Turning away from the month-to-month movements, the chart above shows three- and six-month moving averages of payrolls changes since January 2022. Clearly, the underlying pace of job creation in the U.S. economy has slowed throughout 2023, with the deceleration intensifying between April and August. However, since the end of the summer in particular three-month average payrolls changes recovered, signaling that the strength in today’s report likely is not a one-off. In any case, given today’s data on unemployment and labor force participation, the smoothed trends in payrolls growth run well above the breakeven pace needed to keep the unemployment rate around 3.7% over the next 6 months (purple dashed line in the above chart).

Similar conclusions can be drawn from the household employment survey. Following Shimer (AER, 2005), we can use data total unemployed and employed persons as well as the number of people that are unemployed for less than 5 weeks to estimate:

Job-finding rate: the probability an unemployed person in month t will find a job or leaves the labor force. This is calculated assuming that total unemployment in month t+1 equals month t unemployment plus the number of people unemployed for less than 5 weeks in month t+1.1

Job-separation rate: the probability an employed person in month t will either loses its job, quits or retires, which depends on data on the job-finding rate, unemployment and employment.2

The chart above plot for the most recent period the estimated job-separation. The job-separation rate has been relatively stable over the period, with a very moderate downward shift in 2023 that stabilized since the summer, as lay-offs remained stable. As such, the slight decline in the job-separation rate earlier in 2023 likely reflected a normalization in the quits rate 2019 levels and continued retirement of older workers.

More pronounced moves can be observed for the estimated job-finding rate (chart above). The job-finding rate fell off markedly after March and fell from a probability a person no longer is unemployed in a given month equal to around 55% in early 2023 to close to 45% by the summer. Given the earlier discussed muted decline in job-separation rate over the same period, this likely reflected a significant decline in hiring by firms. However, since the summer the job-finding rate, and thus implicitly hiring by firms, recovered, which suggests more labor marker strength is in the pipeline for year-end and heading into 2024.

Finally, what did this week’s data reveal about wage growth? Average hourly earnings firmed up over the month in November to 0.4% month/month and remained stable in year/year terms at 4%. The wage data from the jobs report are notoriously noisy, given that they are revised often and do not correct for the sectoral and skills composition of jobs growth over the month. There are better quality wage data available, such as the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker and the ECI, but the Atlanta Fed does construct a rudimentary composition correction for average hourly earnings from the jobs report, which can be found here.

The chart above chart makes clear that throughout the year composition-corrected average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers has slowed from the very elevated rates seen in 2022. Since the summer, however, the pace of wage disinflation slowed with momentum seemingly petering out recently. And it is not clear if the current pace of wage growth is consistent with a 2% PCE inflation rate over the medium term.

When I combine the above discussed revised labor productivity and labor share trend estimates with the 2% inflation target, along the lines I do in my usual monthly “Wages and Inflation Expectations” note, the November medium-run annual wage growth rate consistent with 2% inflation stands at about 2.6% (purple line in the above chart). So, the Fed will need to see more progress on wage disinflation for it to be confident that in particular core services excl. housing PCE inflation will eventually slow enough to move overall core PCE inflation on a sustained path back to 2%.

Final Words

This week’s data on productivity and the labor market suggests that the labor market remains tight. While that is a good sign in that a recession is not imminent, it also means that it will keep the Fed on hold in terms of its interest rate policy, especially given the slow progress on wage disinflation. Market participants should expect a robust pushback from the Fed after the upcoming FOMC meeting against the timing and magnitude of rate easing that currently is priced in the yield curve.

Given this calculation, the job-finding rate will run up to October utilizing data on (short-term) unemployment for November.

As the calculation of the job-separation rate depends also on (short-term) unemployment for November, we cannot go beyond October.