July Payrolls: Caution But No Panic

July payrolls growth slowed notably. Despite stable job-finding rates the unemployment rate rose, some of it likely temporary. Wage growth remains elevated.

Today’s release of the July Employment Situation report struck like lightening. Payrolls growth slowed notably, the unemployment rate rose significantly, but wage growth remains elevated. The Fed will take note but will also look at some of the temporary factors underlying this report.

Key takeaways:

Payrolls growth slowed notably, but trends remain solid and above the breakeven pace needed to keep the unemployment rate constant.

The unemployment rate hit 4.3% as the labor force participation rate increased from 62.6% to 62.7%.

The job-finding rate was broadly unchanged over the month at 43% with smoothed trends declining below 50%. The unemployment rate consistent with recent job-separation and job-finding rates is rapidly honing at a level where demand and supply of workers is more balanced. This suggests a negative near-term outlook for the official unemployment rate.

Wage growth remains elevated, with momentum in composition-adjusted average hourly earnings picking up.

Today’s data confirms the Fed’s switch to more emphasis on the employment side of its mandate relative to that for inflation in determining its future policy rate path. But it will also take note of some the temporary factors driving today’s report.

July Jobs Growth: Slowing Down

The July jobs report released today indicated that payrolls in the establishment survey surprised to the downside as they were up by 114,000 persons in July, compared to a 179,000 increase in the preceding month (which was revised down from 206,000 initially). Payrolls growth for May and June combined were revised down 29,000 persons.

The unemployment rate increased 0.2 percentage point to 4.3% in July. In three-digit terms the unemployment rate went up from 4.054% in June to 4.252%. Household employment grew again in July, but a slower pace: from +116,000 persons in June to +67,000 persons (chart above). Meanwhile, the labor force grew by a substantial 420,000 persons, outpacing a population growth of 206,000 persons in July and this resulted in a higher labor force participation rate at 62.7% relative to 62.6% in June. About 70% of the 352,000 persons increase in unemployed people in July was due to temporary layoffs, likely owing to large retooling of auto production plants and the aftermath of Hurricane Berry.

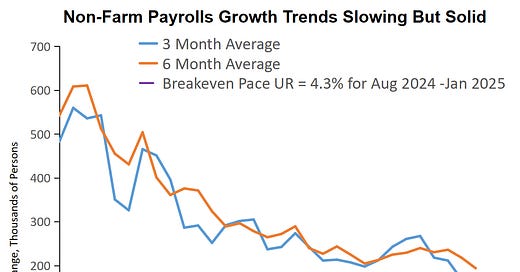

Moving beyond the month-to-month movements, the chart above shows three- and six-month moving averages of payrolls changes from the establishment survey since January 2022. Smoothed trends in payrolls growth have slowed recently but remain in the 150,000-200,000 persons range, which is well above the breakeven pace needed to keep the unemployment rate at 4.3% over the next 6 months (purple dashed line in the above chart).

Additional details about the underlying strength of the labor market can be inferred from the household employment survey. Following Shimer (AER, 2005), we can use data on total unemployed and employed persons as well as the number of people that are unemployed for less than 5 weeks to estimate:

Job-finding rate: the probability an unemployed person in month t will find a job or leaves the labor force. This is calculated assuming that total unemployment in month t+1 equals month t unemployment plus the number of people unemployed for less than 5 weeks in month t+1.1

Job-separation rate: the probability an employed person in month t will either loses its job, quits or retires, which depends on data on the job-finding rate, unemployment and employment.2

The chart above shows a plot for the estimated job-separation rate. This job-separation rate has been relatively stable over the past two year, with a moderate downward shift in the first half of 2023 that stabilized between June and October, but then rose again until recently, as layoffs and retirements picked up. Note, however, that the chart above also makes clear that the variability in the separation rate has been really modest.

Job separations jumped up between June and July (chart above). As the JOLTS report continues to suggest low and declining quits and layoff rates, this might well be driven by the sharp increase in temporary layoffs mentioned earlier. As such job separations might very well decline again in August. Job separation rates remain below those seen in 2022.

In 2023 the job-finding rate declined a lot after Q1 2023 (chart above) but recovered since the summer, rising to about 54% on the month and 52% on a three-month average basis in December.

However, in 2024 the job finding rate declined again. However, it remained relatively stable for people who were unemployed in June going into July. In July the total number of unemployed persons and the number of newly unemployed persons (less than 5 weeks in duration) both increased at fairly similar paces: +352,000 vs. +223,000. This suggests that the likelihood to exit unemployment between June and July did not change much, with the job-finding rate remaining put in the 42%-43% range for June (chart above). Three- and six-month averaged job-finding rates for June declined to around 47%.

As in Shimer (AER, 2005) we can combine the above discussed job separation and job finding rates to calculate a flow-consistent unemployment rate and the chart above plots the three-month average of this rate. The three-month average flow-consistent unemployment rate is the unemployment rate that prevails when the job separation and job finding rates remain constant at their current three-month average levels. Deviations compared to the official unemployment rate should dissipate over time, and often leads changes in the official rate.

Since January the flow-consistent unemployment rate has been outpacing the official unemployment rate and leading the rise in the latter (chart above). It is largely driven by a deterioration in the job finding rate over that period with job separations adding to it more recently, and it suggests substantial labor demand weakening. This is the mirror image of what happened in 2022 and suggests the potential of further unemployment rate increases in the near term.

Whether the recent cooling of the labor market is a prelude to the economy slipping into a recession or simply the labor market becoming more balanced is unclear. One way to look at this more quantitatively is to approximate that level of the unemployment rate at which the unemployment and job vacancy rates are equal on the Beveridge Curve. Michaillat and Saez (2024) show that this rate can be easily approximated by a geometric average of the unemployment and job vacancy rates.

The gray line in the chart above shows that on a three-month average basis this ‘balanced labor market” unemployment rate declined from about 5.3% in January 2022 to about 4.4% in June 2023. That chart also makes clear that in particular the flow-consistent unemployment rate is rapidly converging on the ‘balanced labor market’ rate, suggesting some stabilization might be ahead for the fall.

Nonetheless, the actual unemployment rate is still rising in response to labor market flows, triggering the Sahm rule. But this would NOT necessarily mean a recession, but rather a technical side effect of unemployment returning to trend. And the earlier discussed temporary factors driving up unemployment (more supply, high temporary layoffs) only would reinforce this interpretation.

Wage Growth Remains Elevated

Average hourly earnings of all private sector employees slowed over the month in July to 0.2% month/month from 0.3% in June and decreased substantially in year/year terms from 4.6% in June to 2.9%. For production and non-supervisory workers, hourly earnings grew at an essentially unchanged pace 0.3% month/month in July, and on a year/year basis growth slowed from 4.5% (upwardly revised) to 3.4% in July.

The wage data from the jobs report are notoriously noisy, given that they are revised often and do not correct for the sectoral and skills composition of jobs growth over the month. There are better quality wage data available, such as the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker and the Employment Cost Index, but the Atlanta Fed does construct a rudimentary composition correction for average hourly earnings from the jobs report, which can be found here.

We can observe from the chart above is that easing in the year/year wage growth rate might well be due to base effects (as the year/year rate rose substantially in July 2023). On a three-month basis wage growth picked up notably.

I can combine labor productivity and labor share trend estimates with the 2% inflation target, along the lines I have done in my “Wages and Inflation Expectations” notes and incorporating the Q2 update of productivity data to get a medium-run annual wage growth rate consistent with 2% inflation. Additionally, instead of the 2% target one can use my “Main Street” year-ahead inflation expectations proxy, which after incorporating July inflation survey data suggests that the trend in near-term inflation expectations picked up in Q2 compared to Q1 and are at around 2.75% in year/year PCE inflation terms in July.

Compared to the composition-adjusted AHE data for production and non-supervisory workers, annual wage growth still outpaces the 2.5% pace consistent with 2% PCE inflation in the medium term (green line in the above chart). In fact, sticky “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations seem to put a floor under wage growth well above this target-consistent pace (blue line in the chart above).

September Rate Cut

After the July FOMC meeting it is clear the Fed no longer is singularly focused on bringing inflation back to 2%, but also is emphasizing more the employment side of its dual mandate given the cooling in the labor market. Today’s data will confirm for Fed officials that this indeed was the right change of emphasis.

I very much doubt that today’s data suggests that not cutting rates at the July meeting was a policy error. A slowing in payrolls growth was overdue given the restrictiveness of monetary policy and the one should expect the unemployment rate to rise given labor demand and supply moving more in equilibrium. On top off that a number of temporary factors likely led to an outsized increase in unemployment in July, which may well reverse in August. And the pick-up in wage growth momentum in July still signals an inflation risk.

As such, the July jobs report will be taken as validating the change in policy rate strategy that was signaled at the July FOMC meeting, with a rate cut in September as the likely outcome. The Fed needs to see more data on the labor market and inflation to assess whether the rate easing path after the September FOMC meeting can remain cautious or needs to be more aggressive.

Given this calculation, the job-finding rate will run up to May utilizing data on (short-term) unemployment for June.

As the calculation of the job-separation rate depends also on (short-term) unemployment for May, we cannot go beyond April.