May FOMC Meeting: Holding Off ... Again

With data pointing to a disappointing lack of disinflation amidst solid real activity, the FOMC today signaled rate cuts are off the table for at least H1 2024.

As expected, the May FOMC meeting decision did not result in a change in the Fed funds rate target range. The statement confirmed the disappointment with the lack of progress in recent inflation data that he and other FOMC members expressed in public statements during the intermeeting period:

“Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated. In recent months, there has been a lack of further progress toward the Committee's 2 percent inflation objective.”

During the post-meeting press conference Chair Powell made clear that the Fed funds rate will remain on hold for the foreseeable future until the inflation data turns more favorably.

Key takeaways:

The FOMC decided to keep the Fed funds target rate unchanged at 5.25%-5.50% and signaled a bias to keep rates on hold for several meetings. Additionally, QT will be tapered starting in June with the cap on Treasury redemptions dropping from a monthly $60 billion to $25 billion.

Underlying inflation no longer points to continued substantial disinflation going forward, while near-term “Main Street” inflation expectations bottomed in Q1 2024.

The labor market, wage growth and consumption spending remain relatively strong.

Since the March FOMC meeting, expected near-term real interest rates have been in line with the Fed’s own assessment of its stance.

As the expected year-ahead real rate path remains restrictive and real economic activity levels remain strong, the FOMC will continue to be patient and wait for more progress in inflation data as well as labor market trends before deciding to cut policy rates.

Trends in underlying inflation suggest Fed funds rate cuts now likely do not to start until the September FOMC meeting, with the June FOMC meeting likely being used to signal a lower total amount of rate cuts on the back of a notable upgrade in the Fed’s own neutral rate estimate.

However, if by the September FOMC meeting the data trends are still such that it remains hard for the Fed to embark on rate cuts, I do believe the Fed will take the current easing bias off the table and raise the possibility a recalibration towards a more restrictive policy stance might be needed beyond that meeting.

The Fed’s Disappointment: Lack of Disinflation

The Fed has focused for a while on developments in core services excl. housing inflation. The latter component of core inflation is mainly driven by:

Labor costs, as most of the categories in core services excl. housing inflation are labor-intensive in nature.

Consumption expenditures, as the bulk of U.S. consumption spending is traditionally geared towards services spending.

Non-housing core services inflation has been sticky around 4% for most of 2023, but in Q4 it appeared to ease in a tentative sign that it might finally start to break free from this 4% trend. However, since the end of 2023 this disinflationary trend reversed, and this became even more evident in March (chart above).

This recent strength in non-housing core services inflation reflects a more broad-based pick up in underlying inflation rates: a variety of central tendency measures of inflation (which eliminate the most volatile inflation components) have been firming on a six-month basis since late 2023 (chart above). The PCE-specific measures point to an underlying medium-term trend of about 3% core PCE inflation.

Given the dominance of non-housing services in the core PCE price index (about 55% of the core index), labor costs remain an important factor behind the stalling of disinflation. Indeed, the release of the Q1 number of the Fed's favorite gauge of wage inflation, the private sector wage component of the Employment Cost Index (ECI), confirms what I have been signaling in my regular "Wages and Inflation Expectations - Update" posts over the past few months: the slowing of wage growth is petering out and is settling at a level above the pace consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium term (chart above).

Many analysts as well as often Fed officials have expressed a confidence that in the end disinflation will pick up notably later in the year despite elevated labor costs keeping non-services inflation elevated. This all rests on the hope that declining market rents will start to dominate the housing services component of inflation, pushing core inflation back on a path to 2%. However, as I noted earlier on LinkedIn as well as Twitter, data on new rents sampled from the BLS' own housing survey are heavily revised with revisions generally to the upside (chart above). So, it is better to be cautious when basing forecasts on these measures of new rents. Chair Powell confirmed this when he mentioned at Q&A at the press conference that he believed that are substantial lags with which market rents affect the housing services components of inflation.

Given these developments, it is not surprising that the Fed signaled that they would stand pat for the time being and pushed out expectations of rate cuts into H2 2024. The only way I can see the Fed deviating from this path is if the real economy will slow down notably when we head into the summer. Recent data trends suggest that this is unlikely:

The labor market remains really solid with job finding rates recovering (chart above), as well as solid payrolls and wage growth rates, with latter remaining elevated at an above-inflation target pace.

Underlying consumption spending trends have been picking up again, as household wage income grows faster than what is consistent with 2% PCE inflation in the medium term (chart above). This and the remaining excess savings suggest that we can expect to see solid consumption growth over the next two to three months.

Real Rates Remain Key for Rate Cutting Prospects

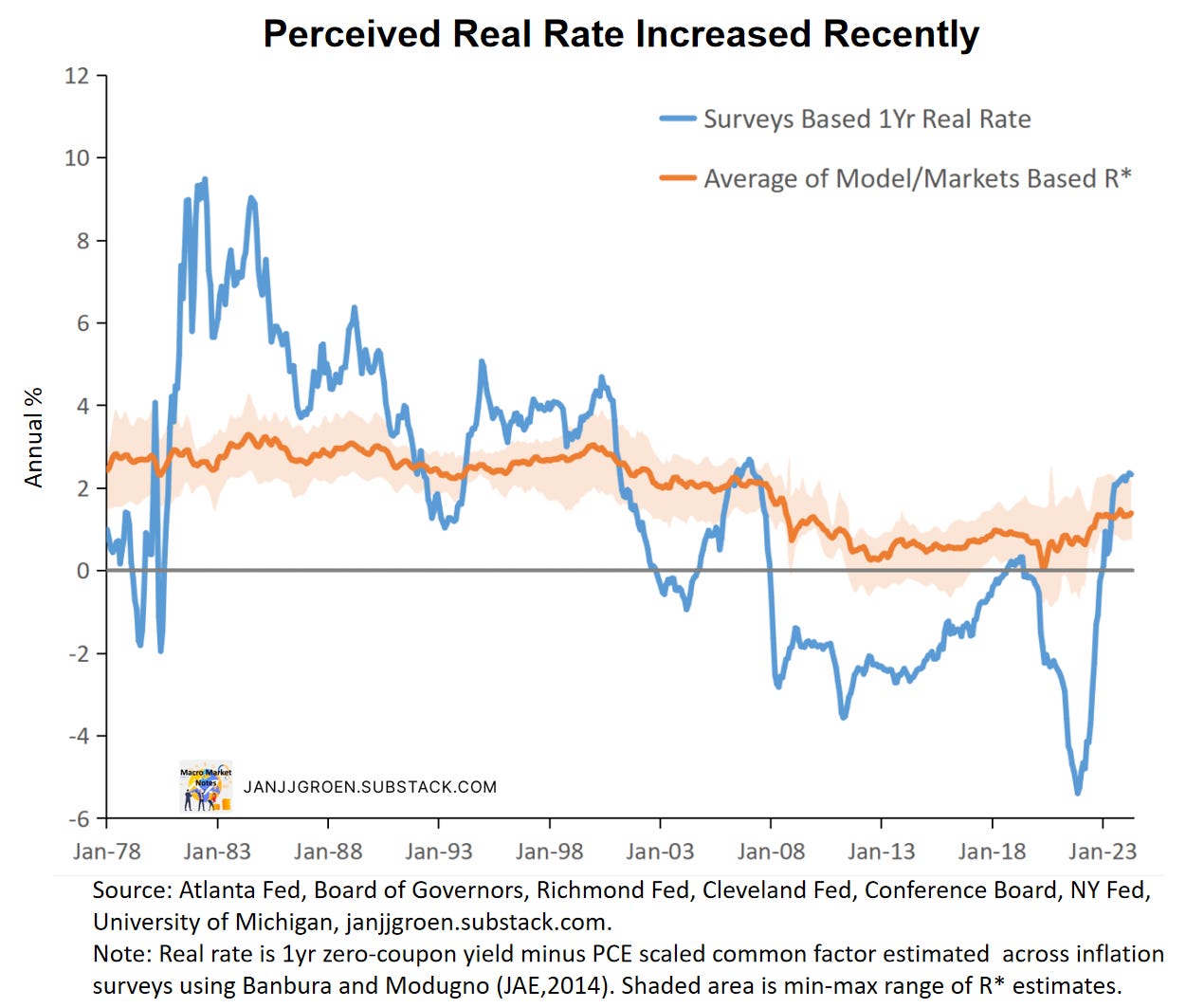

To gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is I published back in August an analysis that focused on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the chart above that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

Key to assessing the restrictiveness of these one-year real rates is where neutral real rates are heading. The chart above is an update of an earlier chart and shows that after close to a decade of ultra-low neutral real rates, these rates have trended up since 2016. Since the fall these R* estimates plateaued with the average across the proxies sitting at 1.38% in April, above the 0.6% rate as implied by the Fed’s March SEP.

The perceived policy stance as depicted by the survey-based one-year real rate in the chart above only became significantly restrictive (by rising beyond the majority of approximate neutral real rate levels) by the summer of 2023. Since then, as “Main Street” near-term inflation expectations eased into Q1 2024 and excessive rate cuts were priced out of the market rates, the expected restrictiveness of the Fed’s policy stance increased in Q4 2023 and Q1 2024.

The chart above contrasts my surveys-based one-year real rate relative to the average of model- and market-implied R* estimates with a proxy of the Fed’s view on this real rate gap using information from its own Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). This chart suggests that since the March FOMC policy stance expectations from “Main Street” and markets have realigned with the Fed’s own assessment of the restrictiveness of its stance over the year.

Of course, this realignment obscures the different drivers in the perceived stance between the Fed and the rest of the economy: the March SEP suggested year-ahead inflation expectation of 2.6% inflation, 2-to-3 rate cuts in 2024 and a R* estimate of 0.6%, whereas “Main Street” and markets expect a somewhat higher year-ahead inflation (2.7% in April), 1-to-2 rates cuts and a higher R* estimate.

Looking Beyond Today

With spot inflation data exhibiting a loss in disinflation momentum, the Fed’s will buckle down on keeping rates at current levels. As I showed earlier, in inflation expectations-adjusted terms rates have become more restrictive over the past months. Keeping the Fed funds rate on hold will allow the Fed to let the higher expected real rates cool economic activity further in order to get inflation back on track on a path towards 2%.

As today’s statement made clear the Fed’s bias is still towards cutting policy rates at some point, putting all of the above together this likely means a postponement of the starting point of a rate easing cycle from initially the June FOMC meeting towards the September FOMC meeting. However, with recent stronger inflation data this poses the risk that over the coming months the expected real rates could ease and derail the effectiveness of the rate holding strategy. And the recent easing in financial conditions only reinforces this possibility.

More specifically, the longer elevated inflation rates last the more it could lead to higher near-term inflation expectations, leading to lower real rates instead of keeping them at current levels. In order to anchor expected real rates at current restrictive levels I expect that at the June FOMC meeting the Fed will signal with its updated projections a lower total amount of rate cuts in 2024 and 2025, motivated by a notable upgrade in its own estimate of the neutral interest rate.

However, if by the September FOMC meeting the data trends are still such that it remains hard for the Fed to embark on rate cuts, I do believe the Fed will take the current easing bias off the table and raise the possibility a recalibration towards a more restrictive policy stance might be needed beyond that meeting.