June Personal Income & Outlays: Ever So Slowly?

Consumption growth was strong, also in underlying terms. Core services inflation eased but underlying inflation rates remain stubbornly above the 2% target.

The June Personal Income and Outlays report provides a good insight on the U.S. consumer as well as inflationary pressures going forward. This note presents some of these insights.

Key takeaways:

Personal income growth out of wages and salaries decelerated somewhat in June. Household wage income growth now runs in line with the pace that’s broadly consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium-term.

The stock of excess savings has NOT run out and continues to be a tailwind for consumption. Between May and June, it fell around $27 billion and equaled about $505 billion in June.

In Q2 2024 headline consumption growth accelerated above underlying spending growth. Beyond Q2 headline spending will likely ease towards the pace of underlying consumption growth. But as the latter remains above its 2022 pace this does not signal that a large downshift in consumption is forthcoming in H2.

Core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, remains at elevated levels but continued to show a slowing in momentum. The central tendency of PCE inflation currently suggests underlying inflation at around 2.8%.

Momentum across most underlying inflation measures is slowing towards target such that it makes a rate cut possible. But the different underlying inflation measures are now signaling a more scrambled picture and with solid underlying consumption growth rates this suggests that the Fed will likely be patient and await the July inflation data before making a rate cutting decision at its September FOMC meeting.

Wage Income Growth Relatively Stable

A dominant source of household income is personal income out of wages and salaries. Today’s report showed a minor downward revision to growth of household income out of wages and salaries for the preceding month (chart below).

The year/year growth rate in June decelerated somewhat compared to May (chart above), as it decreased to 4.1% from 4.3% (down from 4.5% initially). Note that overall personal income growth remained broadly unchanged at around 4.5% year/year, so growth of non-wage income supported annal household spending growth in June.

To interpret wage income growth trends, I earlier proposed to compare wage income growth with a neutral benchmark growth rate based on trend non-farm business sector (NFB) output growth and either the abovementioned common inflation expectations factor or the 2% Fed inflation target. Similar to what I did when discussing wages and inflation expectations in my October 2023 update, I now also incorporate trend labor share growth into this neutral benchmark.

Any deviation in actual household wage income growth above or below the aforementioned inflation target-consistent neutral benchmark means household wage income growth outpaces or cannot sustain in the medium term the 2% inflation target.

The chart above shows that with the downward revision of wage income growth in May and the slight deceleration of it in June, the wage income growth gap based on the Fed’s inflation target essentially closed. Nominal wage income growth thus remains broadly consistent with a pace that should be able to bring inflation close to target in the medium term.

Pace of Excess Savings Drawdowns Remains Gradual

Household spending was up 0.3% over the month in May, whereas disposable household income grew 0.2% for the same period. As a consequence, the savings rate moved down from 3.5% in May (downwardly revised from 3.9%) to 3.4%.

The chart above shows that the savings rate remains below my trend savings rate estimate of 4.7% (down from a downwardly revised 4.8% in May) using the ‘average of trend’ approach outlined in my earlier excess savings note (orange line). Both remain below trend savings rate assumptions used elsewhere (grey and yellow lines).

Given the notably downward revision in trend savings rate estimates earlier in Q2 (May was revised down to 4.8% from 5% initially), in June cumulative excess savings declined from $533 billion in the previous month (revised up from $499 billion) to about $505 billion (see chart above).

Above-trend growth in disposable income continues to be a partial offset to the drawdowns in excess savings coming from above-trend growth in consumption spending and interest payments.

Solid Underlying Consumption Growth

As is the case with headline inflation, headline real consumption spending growth often is driven by volatile components that not always reflect the underlying strength of the economy. A core real consumption spending growth measure, therefore, would be really useful, and I do that by approximating such a core measure based on the weighted median across 177 components1 of headline real personal consumption expenditures (PCE). More specifically, the core, or underlying, consumption growth measure equals the growth rate of the real PCE component at the 50% percentile across growth rates of these 177 sub-components of headline real PCE.

The chart above focuses on three-month annualized consumption growth rates. After accelerating notably during most of 2023, underlying (or core) consumption growth decelerated and stabilized around a 1.5% annualized 3-month rate, higher than the 1% pace observed for 2022. Headline consumption growth overshot the underlying rate by the end of 2023 and the subsequent weakening in real headline spending during Q1 2024 was the consequence of a correction back towards underlying spending growth.

In Q2 2024 headline consumption growth accelerated above underlying spending growth again. Underlying growth also picked up, especially in May in contrast to the previous vintage of data that suggested stable underlying growth for that period. In June underlying consumption growth eased again but headline remained above the median growth pace.

The chart shows a similar comparison between headline and median consumption growth based on six-month growth rates. Since the start of the year six-month rates of headline spending eased towards its underlying counterpart, with the latter sitting at a notably higher level than where it was in 2022 (and appears to drift up further).

So, household spending was strong in Q2 at an above-trend pace. Going into Q3 headline consumption spending likely will ease somewhat in line with underlying consumption growth with the latter remaining above its 2022 pace. A large downshift in consumption is unlikely in H2 2024.

Underlying Inflation Rates Remain Above 2%

In terms of inflation, core PCE inflation picked up in June to about an 2.2% annualized monthly rate from an upwardly revised 1.5% rate in May. Core goods inflation accelerated again to +1.2% annualized month/month from -2.2% in May, whereas core service inflation eased up to 2.5% annualized month/month in May from an upwardly revised 2.8% in the preceding month.

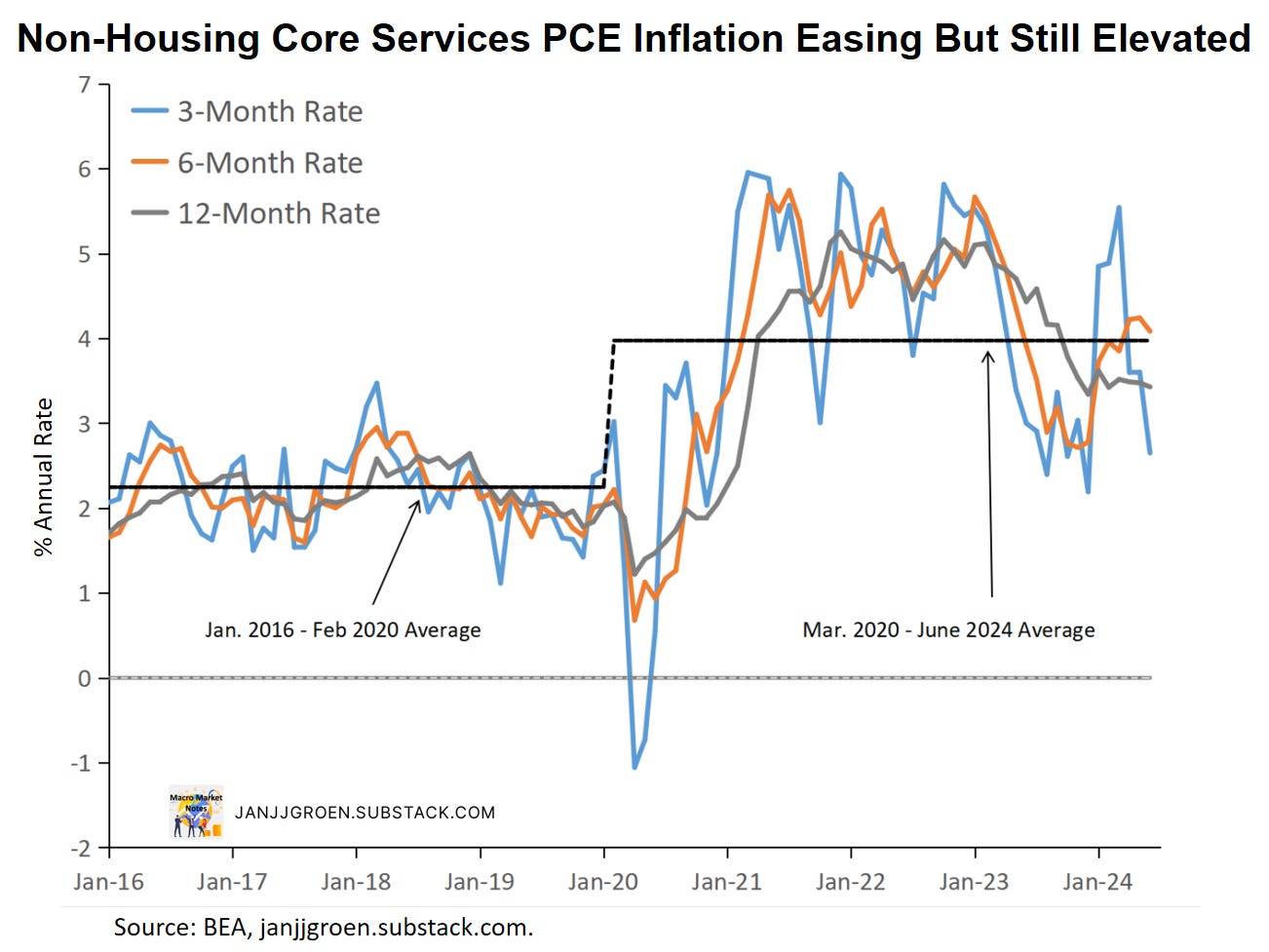

Despite a slower core services inflation rate, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, core services excl. housing PCE inflation, saw an increase in its pace (an upwardly revised) 2.1% annualized month/month to about 2.3%. Given the large volatility in this measure since late 2023 it seems worthwhile to smooth through noisy month-over-month dynamics.

The chart above plots three-, six- and 12-month annualized inflation rates for the non-housing core services PCE deflator. The average annualized monthly rate still reads about 4% for the post-COVID era (black dashed line), two times the average rate we observed for the immediate years pre-COVID.

The momentum measures in the chart above have been sticky around 4% for most of 2023. But in Q4 2023 momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation appeared to ease but this disinflationary trend reversed in Q1 2024. Since April, momentum in this non-housing core services inflation measure slowed again and it continued to do so in June, but its rate remains still quite elevated compared to pre-2020 averages.

Instead of focusing on whether specific components of inflation should be ignored or not when assessing underlying inflation trends, one could focus on the central tendency of consumer price inflation, a.k.a. the center of the distribution of all price changes unaffected by extremely volatile consumer price components. This could potentially provide a better sense of the target toward which inflation moves over time once those excessively volatile price changes have stabilized.

Such measures of central tendency for the PCE price indices use a variety of trimming procedures to weed out excessive volatile components of these price indices in a given month:

Median CPI, which takes the inflation rate of the component at the 50% percentile of the CPI component price changes.

Trimmed Mean PCE (Dallas Fed), where the highest 31% and lowest 24% of PCE component price changes are dropped.

15% Trimmed Mean PCE, where the highest 7.5% and lowest 7.5% of PCE component price changes are dropped.

20% Trimmed Mean PCE, where the highest 10% and lowest 10% of PCE component price changes are dropped.

30% Trimmed Mean PCE, where the highest 15% and lowest 15% of PCE component price changes are dropped.

The chart above scales each of these measures into a three-month average distance relative to 2% core PCE inflation as a measure of the Fed's inflation target. In Q1 2024 all underlying three-month average inflation rates sharply overshoot the Fed's inflation target. But since April this overshoot eased notably with the three-month average deviations dropping towards the inflation target except for the median PCE inflation measure that remains stable well above the target. This could be a sign that some of this easing momentum might not last going forward.

Alternatively, it might be more insightful to look at the smoother six-month averages of the annualized percentage point deviation of monthly central tendency inflation measures relative to their values as implied by 2% core PCE inflation. This is also consistent with recent public statements by Fed officials that they’d like to see sustained progress of inflation converging back to target. For example, the newly minted St. Louis Fed President Alberto Musalem suggested it "[...] could take months, and more likely quarters [...]" of inflation progress before he'd be comfortable with policy easing. My interpretation of these statements is that Fed officials would be more inclined to start cutting the Fed funds rate if the annualized six-month average reading across underlying core PCE inflation rates would hit 2.5% or less.

The chart above suggests a qualitatively similar story as for the three-month average measures: a lot of progress was made by the end 2023 in terms of a return back towards the Fed’s 2% inflation target, but in 2024 this progress stalled.

With upward revisions to PCE price data in April and May, the six-month average deviations of underlying PCE inflation rates relative to the inflation target in the chart above suggest that underlying PCE inflation trend remains around 2.8%, despite the downward momentum in Q2. And as was the case for the three-month averages, the Median PCE inflation measure suggests persistently higher overshoot.

Given where underlying inflation rates are a three-month average basis, it is possible further slowing over the summer could push the six-month average underlying PCE inflation trend to around 2.5% by the time of the July Personal Income & Outlays report. But the different central tendency inflation measures are starting to signal a difference in tendency over that horizon.

Given the momentum in underlying inflation rates it is possible that by the time of the September FOMC meeting Fed officials have seen enough of a sustained progress on inflation to be comfortable with commencing rate cuts. However, underlying inflation rates are signaling a more scrambled message of the past three months, and this puts a lot of burden on the July data to give the Fed more comfort inflation progress is not stalling again and to decide to cut rates in September.

Given still strong underlying spending growth the Fed can afford to wait until its September FOMC meeting to make the decision to start easing policy. But this is by no means certain, and a lot will also depend on incoming data on the labor market.

For a description of these 177 components, see Appendix A in the Dallas Fed trimmed mean PCE inflation working paper, where I use the corresponding real quantities instead of the price indices.