"Main Street" Inflation Expectations and Jan FOMC Preview

"Main Street" expectations were firmer for both December and January, with the potential for a further rise ahead. The Fed will likely stay on hold.

This post reviews recent trends in inflation expectations from firms’ and household expectations. I’ll also preview the upcoming January FOMC meeting.

Key takeaways:

Near-term inflation expectations from a variety of consumer and firms’ surveys point to a pickup in expectations in January, with increased policy uncertainty, especially pertaining tariffs, mentioned as a main cause.

Longer term household inflation expectations not only are higher compared to 2016-2019 but also the distribution of responses have become increasingly more tilted to the upside. The latter trend intensified during the final half of 2024.

At the upcoming January FOMC meeting it is very likely that policy rates remain on hold. Both the data and Fed officials’ remarks underscore this, and therefore the post-meeting statement and press conference should not be dramatically different compared to the December meeting.

Inflation Expectations on Edge?

The University of Michigan's January Consumer Sentiment Survey saw sentiment decline for the first time since March 2024, despite improved personal finance assessments. Declines were broad-based across income, wealth, and demographics. Notably, inflation expectations jumped: the median one-year outlook rose from 2.8% in December to 3.3% in January, while long-term (5-10 years) expectations increased from 3% to 3.2%. Policy uncertainty tied to the new administration in DC played a key role, with the report highlighting inflation concerns linked to anticipated policies like tariffs.

The rise in one-year expectations in the Michigan survey aligns with upticks in the January’s Atlanta Fed Business Inflation Expectations Survey and Conference Board Consumer Confidence Survey (both +20bps) as well as an increase in the December expectations from the NY Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations. The chart above shows the common trend estimated from firm and household inflation surveys, as I’ve outlined here, incorporating the latest data. This suggests "Main Street" expectations rose from about 2.4% in year/year PCE inflation terms in Q4 to around 2.7% in January—the highest since May 2024.1 These findings point to heightened short-term inflation worries, driven by sticky actual inflation data and policy uncertainty.

Long-term median expectations (5-10 years ahead) from the Michigan survey have been higher post-COVID than in 2016-2019 (chart above). The survey also provides data on the expectations of respondents at the 25th (Q25) and 75th ((Q75) percentiles of the distribution of respondents in a given month, albeit with a one-month lag. This allows us to quantify how evenly distributed expectations are around the median within the middle 50% of the distribution of respondents. I do that by means of the Bowley skewness: (Q25+Q75-2Median)/(Q75-Q25). As such we have a measure of relative asymmetry of inflation expectations, with positive values indicating respondents are leaning towards higher inflation expectations (with some expectations well above the median) and vice versa for negative values.

From the above chart we notice a growing share of respondents leaning towards higher expectations compared to the median, often leading increases in the median expectation (orange line). By contrast, 2016-2019 saw balanced expectations (gray line near 0). In fact, post-2021 expectations returned to the pre-GFC pattern of upside risks (green line). In H2 2024, these leaned even further above average, reflecting heightened uncertainties around monetary, fiscal, immigration, and trade policies.

Firms and households are increasingly edgy about inflation, driven by elevated inflation volatility since 2020. Comparisons to 2017-2018—years of stable inflation and balanced expectations—when assessing the potential impact of higher tariffs and other policy initiatives are misplaced. Today’s uncertain policies risk driving a sustained updrift in inflation expectations, complicating efforts to stabilize inflation at target. Policymakers (both within the Fed and the new administration) must urgently provide clarity and stability to counter this tendency.

January FOMC Meeting Preview

The 25bps Fed funds rate cut at the December FOMC meeting was clearly the final move in the recalibration move, as described by Chair Powell back in September aimed at lowering the policy rate to be bring it back in line with the disinflation and labor market weakening observed earlier in 2024. So, is after the December rate cut the Fed funds rate at a more balanced level? To answer this question, we can look at rate prescriptions that result from various policy rate rules that relate the Fed funds rate to views about how much inflation deviates from 2% as well as views on whether the unemployment rate is "too low" or "too high". The various policy rate rules differ in their rate prescriptions, owing to

Different preferences to stabilize inflation vs stabilizing the unemployment rate.

What inflation measure you use: current inflation or more forward-looking measures.

Different long-run assumptions, in particular the neutral Fed funds rate level and the long-run unemployment rate.

How (im-)patient central bankers are in pushing the Fed funds rate to its "appropriate" target level.

By running the data through a variety of policy rate rule variants that differ along the lines outlined above and aggregating over the range of rate prescriptions2, you can get a pretty robust sense of the Fed funds rate level that is in-line with the current data.

The numbers resulting from this policy rules exercise with data up to and inclusive of December are depicted in the chart above. From this chart it is clear while in the run up to the September FOMC meeting the Fed funds rate was about 100bps above the fundamentals-based level, by December it’s pretty much aligned with those fundamentals given sticky inflation and a stabilizing unemployment rate.

In fact, the policy rule-based descriptions are showing (very) tentative signs that the policy rate has troughed already. The chart above suggests a ‘no change’ rate decision at the upcoming January meeting could be appropriate, with most FOMC members corroborating this in their public remarks during the intermeeting period.

To gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is perceived to be for the year ahead, I published back in August 2023 an analysis that focused on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the inflation expectations chart discussed in the previous section that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

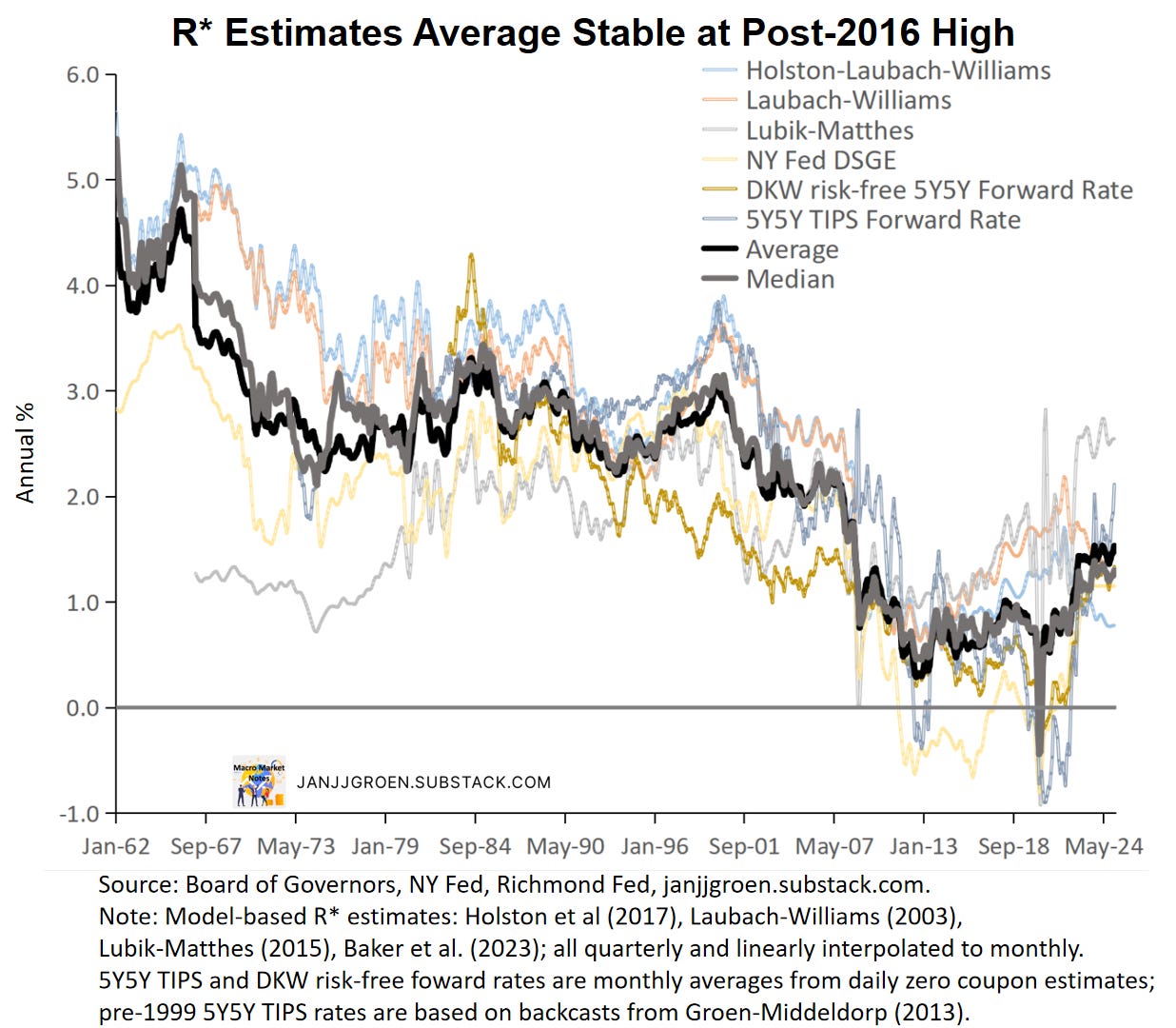

Key to assessing the restrictiveness of these one-year real rates is where neutral real rates are heading. The chart above is an update of an earlier chart and shows that after close to a decade of ultra-low neutral real rates, these rates have trended up since 2016. Throughout most of 2024 and going into 2025, these R* estimates plateaued with the average and median across the proxies sitting at around 1.5% and 1.3% respectively in January, above the median 1% rate from the Fed’s December SEP.

The chart above compares the one-year survey-based real interest rate with the R* range across the various market- and model measures as a perceived policy stance measure. It suggests that the Fed’s stance is expected to be close to neutral in inflation-adjusted terms between now and January 2026 (around 5bps and 28bps above the average and median R*’s respectively) despite using higher R*’s compared to the Fed.

This easing in perceived monetary policy stance came about despite a one-year nominal rate that going into the January did not decline meaningfully (on average around 4.22% up to January 24th compared to a December average of 4.24%). It’s, of course, the close to 30bps firming in inflation expectations discussed earlier that drove most of the perceived stance easing. As a number of Fed officials reaffirmed a desire to keep rates on hold while assessing recent inflation trends and the uncertainty regarding new policy initiatives out of D.C., this easing in the perceived monetary policy stance owing to a pickup in inflation expectations will not be welcomed by some Fed officials:

“I also continue to be concerned that the current stance of policy may not be as restrictive as others may see it. […] In fact, concerns about inflation risks seem to partly explain the recent notable increase in the 10-year Treasury yield back to values last seen in the spring of 2024. In light of these considerations, I continue to prefer a cautious and gradual approach to adjusting policy.”

M. W. Bowman, ‘Reflections on 2024: Monetary Policy, Economic Performance, and Lessons for Banking Regulation ‘, January 9, 2025

So, overall developments in the economy since the December meeting as well as a big emphasis on a cautious rate outlook in Fed officials’ statements likely means that the Fed will remain on hold at its January meeting. Given that the December post-meeting statement already got revamped to signal a very cautious approach to future rate moves given inflation and policy uncertainty as well as a stable labor market, I do not expect it to change after the January meeting.

The only potential source of news could be the post-meeting press conference, although Chair Powell will no doubt do his best to not convey any explicit signals with regards to the future rate setting policy, nor regarding the policies of the incoming administration in D.C., and, instead, emphasize data dependence as a rate setting guide. While this might have been useful in 2022-2023 when swift action was necessarily to break the back of an accelerating inflation rate, it might become problematic now with overall policy uncertainty reaching unprecedented levels. In such circumstances more forward guidance would appropriate, as

“[e]ffective monetary policy depends on clearly communicating our intentions so that the public will act on those intentions. That also requires credibility […]”

C. J. Waller, ‘Challenges Facing Central Bankers ‘, January 8, 2025.

With longer term household inflation expectations leaning increasingly stronger towards higher expectations, as discussed in the previous section, now is the time for the Fed to provide more clarity and steadfastness to counter this trend.

On January 24th I circulated on social media a preliminary estimate of January inflation expectations based on the dynamic factor model incorporating January updates for the University of Michigan and Atlanta Fed surveys here, here and here. This preliminary estimate equaled 2.59% so today’s 2.65% reflects the +20bps increase in January vs December as well as an upward revision to December of +10bps in the Conference Board survey.

For more detail about the different policy rate rule variants that are used in this exercise, see the box at the end of my post-September FOMC post. The only difference compared to that note is that I now not only use the central tendencies for the long-run Fed fund and unemployment rates from the history of SEPs, but in addition also the maximum and minimum for these long-run values. This gives a more complete picture of how the distribution of beliefs evolved within the FOMC. As a result of this addition, the total number of policy rule variants from increases from 1200 to 3600.