November FOMC Meeting Preview: Slowly Easing

With gradually cooling labor markets and still favorable near-term inflation trends, a 25bps rate cut is certain. Don't expect more guidance beyond that.

With labor markets gradually easing, inflation over the past six months slowing towards 2% but household spending running strong, both this week’s FOMC meeting decision as well as the one next month will be essentially on autopilot with 25bps rate cuts for both meetings. The November 5th election result will have zero impact on this path. Beyond 2024, the outlook for the Fed’s policy rate path will be a lot muddier with a possibly fading disinflationary impulse, neutral rate uncertainty and political uncertainty rearing their ugly heads.

Key takeaways:

While underlying PCE inflation trends over the past six months have converged close to 2%, underlying inflation over shorter horizons has picked up. On an annual basis underlying PCE inflation remains stable in a 2.5%-2.6% range.

Although volatile from month to month, labor market activity continues to cool gradually with the unemployment rate range bound between 4% and 4.2%. Real household spending is still growing at a strong pace.

The September FOMC rate decision as well as guidance by Fed officials since then has led to substantially less restrictive expected shorter-term real interest rates.

I expect the FOMC to lower the Fed funds target range from 4.75%-5% to 4.50%-4.75% at the November FOMC meeting. The policy statement will only have minimal changes reflecting a somewhat slower disinflation momentum.

Given a gradually slowing economy but slower inflation moderation, interest rate policy rules suggest that with 25bps rate cuts at the November and December meeting, the Fed funds rate target will become aligned with underlying economic fundamentals by year-end. Expect therefore another 25bps rate cut in December.

A gradually slowing economy, uncertainty regarding the neutral Fed funds rate level, and uncertainty about economic policies of a new Federal administration will mean a more cautious rate cutting path for 2025.

Economic Background

The September Personal Income & Outlays report showed that while on six-month and twelve-month basis non-housing core services PCE inflation is still slowing, near-term momentum has picked up since the summer. Similarly, trimmed mean measures of PCE inflation essentially were at the inflation target when averaged over six-months but picked up steam over shorter horizons. Averaged over twelve months most of these trimmed mean PCE inflation series remains sticky above Fed's 2% inflation target within the 2.5%-2.6% range (chart above).

“Main Street” near-term inflation expectations eased for most of Q2. When I extract the common trend across a variety of firm and household surveys of near-term inflation expectations for September and October (including the Atlanta Fed BIE, the Conference Board and University of Michigan surveys for October), it is clear that since June those expectations eased have been stable in a 2.5%-2.6% PCE inflation scale range (chart above), very similar that what is suggested by trimmed mean PCE inflation measures on an annual basis. Bottom line is that the while over the past six months inflation has been easing in a satisfactorily manner, there appears to be signs more near-term that this easing is losing momentum amidst indications that over the medium-term inflation is settling in the 2.5%-2.6% range.

Since the September FOMC meeting, we had two jobs’ reports. The September jobs report saw an acceleration in payrolls growth as well as a notable drop in the unemployment rate, while wage growth outpaced expected inflation. The subsequent October jobs report was, however, notably softer. Temporary factors like the Boeing strike and severe weather no doubt were driving this downbeat report. Nonetheless, revisions to August payrolls data meant that on a three-month basis payrolls growth has not been keeping up with more aggressive CBO population growth estimates. And labor market flows suggest that it has become harder for unemployed to exit their unemployment status. Thus, we have a lot of uncertainty about how much of the recent additional labor market cooling is temporary or not.

Indeed, underlying labor market flows did indicate a pick-up in the corresponding, flow-implied unemployment rate, but smoothing through the month-to-month choppiness still suggest it seems more likely that the labor market is cooling towards a relatively stable unemployment rate at around 4.2%. This would also be more in line with accelerating growth of consumption spending, and as such it signals a recession should not be a base case for the U.S. economy.

How Restrictive Is the Fed?

To gauge how restrictive the Fed’s interest rate policy is I published back in August 2023 an analysis that focused on a one-year survey-based real interest rate. This rate is calculated by taking the monthly average of daily one-year interest rates and subtracting the (monthly) common inflation expectations factor from the inflation expectations chart discussed in the previous section that is scaled in year-on-year PCE inflation terms.

Key to assessing the restrictiveness of these one-year real rates is where neutral real rates are heading. The chart above is an update of an earlier chart and shows that after close to a decade of ultra-low neutral real rates, these rates have trended up since 2016. For most of the year, these R* estimates plateaued with the average and median across the proxies sitting at around 1.4% and 1.2% respectively in October, above the 0.9% rate as implied by the Fed’s September SEP.

The perceived policy stance as depicted by the survey-based one-year real rate in the chart above only became significantly restrictive (by rising beyond the majority of approximate neutral real rate levels) by the summer of 2023. Until recently, the expected restrictiveness of the Fed’s policy stance hovered at highs not seen since Q4 2000. However, since the 50bps rate cut as well as the signaling of further cuts following the September FOMC meeting year-ahead expected restrictiveness declined rapidly, as inflation expectations remained broadly stable over this period. As of October, the year-ahead real rate in the chart above stands at around 1.6% and is closing in on what market- and model-implied R* measures consider to be neutral.

So, the signaling by Fed officials at the September FOMC meeting and thereafter through public statements has already made the impact of monetary policy substantially less restrictive and close to neutral. Validating this perceived policy stance by means of a path of well-timed, moderate rate cuts seems to be the Fed’s current modus operandi. However, what does this imply for how much and how fast the federal funds rate target likely will be reduced? To help answer this question we can look at rate prescriptions that result from various policy rate rules that relate the Fed funds rate to views about how much inflation deviates from 2% as well as views on whether the unemployment rate is "too low" or "too high". The various policy rate rules differ in their rate prescriptions, owing to

Different preferences to stabilize inflation vs stabilizing the unemployment rate.

What inflation measure you use: current inflation or more forward-looking measures.

Different long-run assumptions, in particular the neutral Fed funds rate level and the long-run unemployment rate.

How (im-)patient central bankers are in pushing the Fed funds rate to its "appropriate" target level.

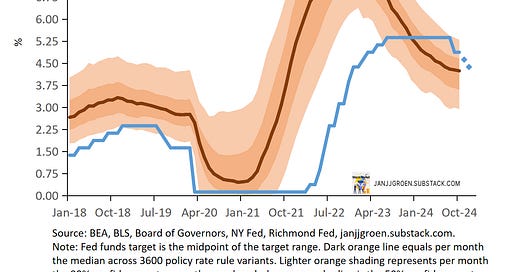

By running the data through a variety of policy rate rule variants that differ along the lines outlined above and aggregating over the range of rate prescriptions,1 you can get a pretty robust sense of where the data suggests the Fed funds rate should be as of now. The chart above suggests that based on the median across the different policy rate rule variants the Fed funds target rate is about 60 basis points too high heading into the November FOMC meeting.

The chart above also indicates that the median policy rule-based rate prescription has been declining at a slower pace since the summer. This lines up well with the macro environment that I summarized in the previous section: fading disinflation momentum with medium-term PCE inflation stabilizing at 2.5%-2.6% and a gradually cooling labor market with the unemployment rate contained in the 4%-4.2% range. And as it is unlikely that the remaining data releases this year would change this assessment, two 25bps rate cuts in November and December (diamonds in the chart above) would therefore more or less realign the Fed funds rate target with the economy’s fundamentals.

“… [S]o most of my colleagues likewise expect to reduce policy over the next year. There is less certainty about the final destination. The median estimated longer-run level of the federal funds rate in the Committee's Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) is 2.9 percent, but with quite a wide dispersion, ranging from 2.4 percent to 3.8 percent. While much attention is given to the size of cuts over the next meeting or two, I think the larger message of the SEP is that there is a considerable extent of policy restrictiveness to remove, and if the economy continues in its current sweet spot, this will happen gradually.”

C. J. Waller, ‘Thoughts on the Economy and Policy Rules at the Federal Open Market Committee‘, October 14, 2024.

Given the above discussed realignment of the policy rate and economic fundamentals, beyond the December FOMC meeting the Fed likely will switch to a ‘skipping mode’ when comes to further rate cuts, with cuts likely happening at FOMC meetings SEP in 2025. So, at most 4 25bps cuts in 2025 and very likely less than that barring a recession occurring next year (Governor Waller’s recent public remarks quoted above are consistent with this view). The slower pace of cutting in 2025 will give the Fed room to assess (a) where the neutral level for the Fed funds target likely is, and (b) what the likely macro impact of the proposed economic policies of a new Federal administration will be. The outcome of these assessments likely determines where the through Fed funds rate target level will be next year: 3.25%-3.5% or higher.

Finally, in terms of the statement, given the rate outlook discussion above I do not foresee any major changes to it. Some changes with regards to inflation developments will likely occur to reflect the earlier discussed tentative signs of a fading disinflation momentum:

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace. Job gains have slowed, and the unemployment rate has moved up but remains low. Inflation has made some

furtherprogress toward the Committee's 2 percent objective but remains fairlysomewhatelevated.The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. The Committee remains confident

has gained greater confidencethat inflation will continue to converge towardsis moving sustainably toward2 percent, and judges that the risks to achieving its employment and inflation goals are roughly in balance. The economic outlook is uncertain, and the Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate.In light of the progress on inflation and the balance of risks, the Committee decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point to 4-3/4 to 5 percent. In considering additional adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage‑backed securities. The Committee is strongly committed to supporting maximum employment and returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

In assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy, the Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook. The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals. The Committee's assessments will take into account a wide range of information, including readings on labor market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.

Voting for the monetary policy action were Jerome H. Powell, Chair; John C. Williams, Vice Chair; Thomas I. Barkin; Michael S. Barr; Raphael W. Bostic; Michelle W. Bowman; Lisa D. Cook; Mary C. Daly; Beth M. Hammack; Philip N. Jefferson; Adriana D. Kugler; and Christopher J. Waller.

Voting against this action was Michelle W. Bowman, who preferred to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/4 percentage point at this meeting.

For more detail about the different policy rate rule variants that are used in this exercise, see the box at the end of my post-September FOMC post. The only difference compared to that note is that I now not only use the central tendencies for the long-run Fed fund and unemployment rates from the history of SEPs, but in addition also the maximum and minimum for these long-run values. This gives a more complete picture of how the distribution of beliefs evolved within the FOMC. This increases the total number of policy rule variants from 1200 to 3600.