Wages and Inflation Expectations - February 2024 Update

Wage growth remains stuck well above the pace consistent with the inflation target. Inflation expectations stabilized around 2.6% in PCE inflation terms.

The monthly update of my wage growth framework, which can be used to interpret wage growth trends relative to inflation expectations and the Fed’s inflation target, is due. The resulting W* measure reflects a trend wage growth rate where demand and supply in the labor market are in balance given an inflation outlook. It is equal to either the 2% inflation target or year-ahead inflation expectations plus a trend labor productivity growth estimate as well as a trend labor share growth estimate. The latter component corrects my original W* for long-run shifts in workers’ compensation as a share of non-farm business sector revenues (a.k.a. the labor share).

With new wage data for January, labor productivity and labor share data for Q4 and updates of inflation expectations data for January and February, this note will update the above-mentioned wage growth framework.

Key takeaways:

Since November “Main Street” inflation expectations eased notably below 3% and appear to have stabilized around a 2.6% PCE equivalent rate in January and February.

Consequently, trend wage growth based on these inflation expectations (W*) eased, which suggests potential additional wage disinflation for 2024.

With W* consistent with about 2.6% PCE inflation, this wage growth trend measure is closing in on the Fed’s 2% inflation target. But any actual wage growth easing in line with this measure will still keep wage growth at an above-target pace.

Actual wage growth measures for January, however, remain stuck at a pace far above the inflation target pace. Corrected for expected inflation, trend productivity growth and trend labor share growth, these continue to boost households’ real incomes and spending.

Inflation Expectations

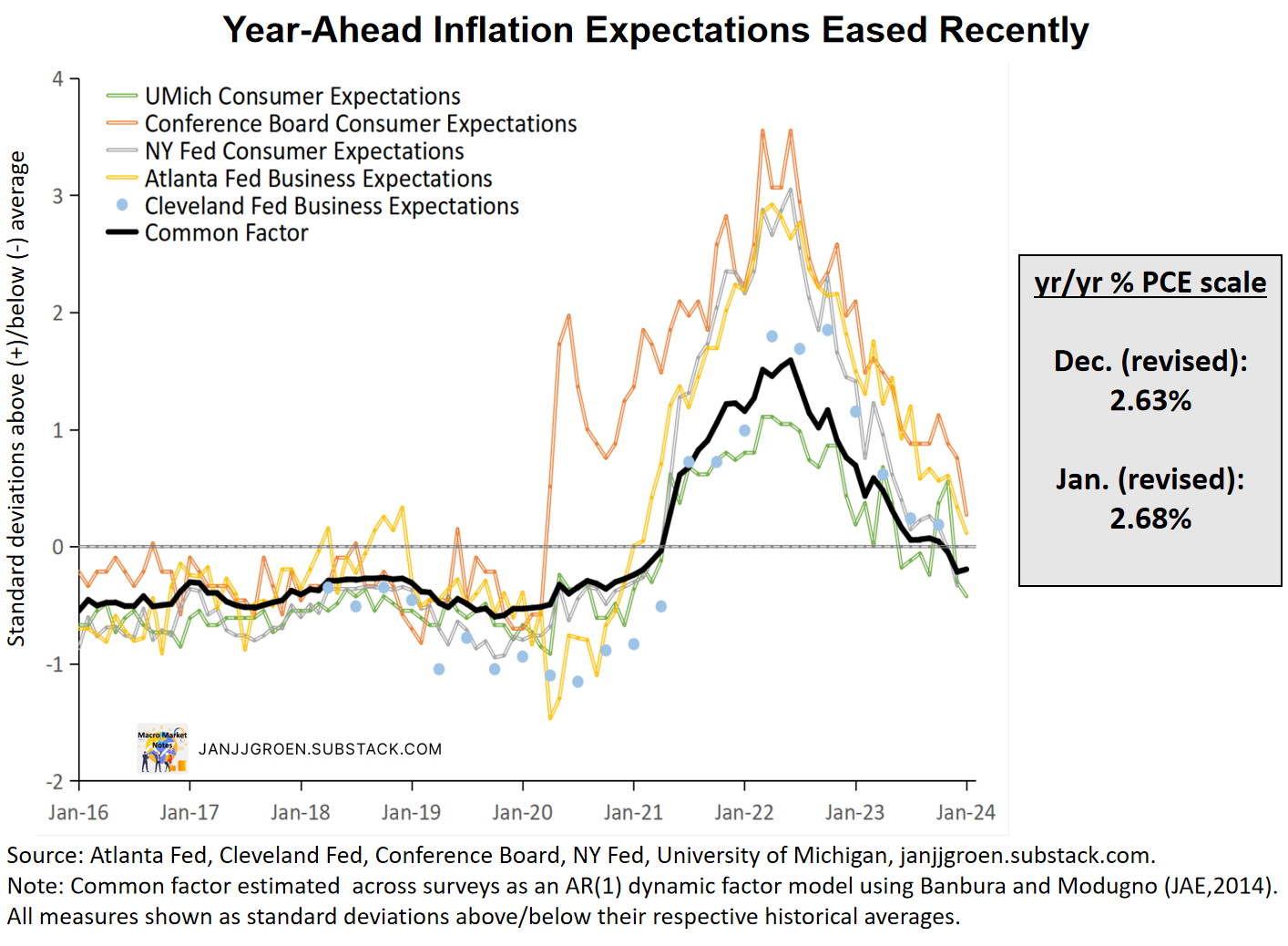

I regularly publish a W* trend wage growth measure that builds on inflation expectation surveys drawn from “Main Street”, i.e., five inflation expectations samples from households and firms. Following my original W* note, I extract a common signal from these inflation survey measures by means of a single dynamic common factor that depends on its own lag using the approach of Banbura and Modugno (JAE, 2014).

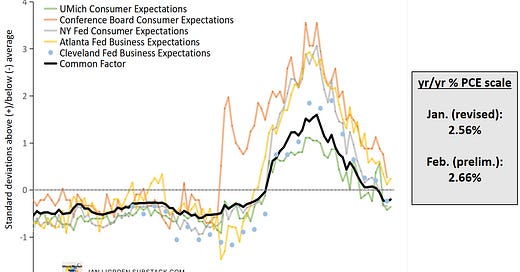

I have plotted in the chart above the available individual expectations series I used for my post-January FOMC meeting note of January 31st alongside the corresponding estimated common factor across these series, as well as the scaling of this factor in year-on-year PCE inflation terms. At that point the common trend across these surveys suggested “Main Street” inflation expectations that had been stuck around 3.2% between July and October but then drifted down to around 2.6% by December and January.

Since the aforementioned December 22nd note, four out of the underlying surveys got updated, two with observations for January and two surveys providing expectations for February:

The February 21st Atlanta Fed Business Inflation Expectations survey for February pointing to a slight tick-up in mean 12-month ahead inflation expectations from 2.23% in January to 2.3%.

The February 16th preliminary University of Michigan survey for February, which showed median year-ahead inflation expectations also increasing slightly from 2.9% in January to a provisional 3%.

The February 12th quarterly Cleveland Fed Survey of Firms’ Inflation Expectations showing a decline in 12-month ahead mean CPI inflation expectations to 3.4% for January from 4.2% for October 2023.

The February 12th NY Fed January Survey of Consumer Expectations that indicated unchanged median year-ahead expectation at 3%.

The re-estimation of the common factor across “Main Street” inflation expectations using these updated individual expectations is depicted in the chart above and now suggests a downward revision to January inflation expectations from previously 2.68% in PCE terms to currently 2.56%. The preliminary estimate for February stands at 2.66%. Therefore, after stalling at a PCE year/year equivalent of 3.2% for July-October “Main Street” inflation expectations have since then declined and settled at a new stable level around 2.6%.

Trend Labor Productivity and Labor Share Growth Rates

Labor productivity remains below-trend so catch-up dynamics will likely keep growth rates temporarily elevated in 2024H1. Nonetheless, the year/year trend labor productivity growth rate for Q3 remains subdued historically at around 1.3% year/year, as is shown in the chart below.

The labor share equals the ratio of total workers compensation relative to nominal output of businesses. As for labor productivity, I approximate the labor share trend by taking the average of six trend estimation methods applied to the actual labor share data, using the methodology outlined in my original W* note.

The chart above shows the labor share trend estimate, which continues to show a drift down. Hence, the wage growth level consistent with the Fed’s inflation target is likely lower than usually assumed in the policy debate given the decline in trend labor share on top of subdued trend labor productivity.

Wage Growth

To recap, to assess wage growth trends I combine the following three elements I discussed in the previous sections, i.e.,

The trend productivity growth estimate described earlier (assuming a Q1 trend labor productivity level based on the trend labor productivity change over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

A similar estimate of trend labor share growth (assuming a Q1 share level based on the trend labor share change over the past quarter, followed by linear interpolation from the quarterly to the monthly frequency).

And, either the year-ahead inflation expectation proxy based on the common factor from firm and household surveys or the 2% inflation target.

The sum of 1-3 above will result in two alternative trend wage (W*) measures, and I compare these below with measures of average hourly wages of workers that are robust to compositional changes over the month.

Wage data from the BLS jobs report are notoriously noisy, given that they are revised often and do not correct for the sectoral and skills composition of jobs growth over the month. There are better quality wage data available, such as the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker, but the Atlanta Fed does construct a rudimentary composition correction for average hourly earnings from the jobs report, which can be found here.

The chart above shows the resulting composition-adjusted average hourly earnings (AHE) wage series for production and non-supervisory workers as constructed at the Atlanta Fed. Although accelerated wage growth in the most recent jobs report might partly be due to weather-related issues, the chart does indicate that three-month growth rates of wages have been accelerating after the summer. Consequently, annual AHE growth for production and non-supervisory workers has stabilized and no longer is slowing.

The chart above shows that both alternative wage growth measures from the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker also have been stable, at around 5.2% year/year, since the summer of 2023, while the smoothed year/year growth of the composition adjusted AHE stabilized around 4.5% in January (purple compound line in the chart above). These wage growth measures have been overshooting the expectations-based W* metric consistently since Q1 2023, suggesting positive expected real wage growth since then and into 2024 Q1.

Compared to the previous update, the year-ahead expectations W* metric declined further (blue line in above chart), in line with the earlier discussed easing in “Main Street” inflation expectations. Nonetheless, we continue to see the same dynamic:

Actual wage growth rates stabilized well above both the expectations-based (currently in line with about 2.6% PCE inflation) and inflation target-consistent W* levels.

With the declining trend in the labor share incorporated into the W* measure, the Fed needs to see year/year wage growth of about 2.6% for it to be consistent with 2% PCE inflation over the medium term.

Implications

The data on “Main Street” inflation expectations do suggest that expectations eased notably over the past three months after remaining stuck for the prior four months. Consequently, the expected degree of easing of wage growth based on inflation expectations picked up again and is approaching the inflation target-implied rate.

Wage contracts typically are staggered across sectors and across the year, so any convergence in wage growth towards rates consistent with the currently implied 2.6% year ahead PCE inflation rate is likely to be gradual. In addition, the catch-up dynamic driving above-trend labor productivity growth have also temporarily kept wage growth north of the inflation target-consistent pace. But if my inflation expectations estimate is indeed representative of more subdued inflation expectations of wage negotiators and labor productivity growth slows towards trend, we should see throughout 2024 a convergence of actual wage growth metrics towards the blue line in the chart above.

On the other hand, the positive expected real wage growth rate seen since Q1 2023 owing to a strong labor market, has been a boost for expected real wage incomes of household. This has resulting in persistently robust levels of consumption spending. Robust household spending could arrest any further disinflation of, in particular, service prices, which then would stop or revert declines in “Main Street” inflation expectations. As a consequence, and the earlier discussed acceleration in three-month adjusted AHE growth might be an early sign of this, wage growth in that scenario could then top out at a rate above the inflation target-consistent rate, reinforcing the “stickiness” of services inflation.

Because of the above as well as the current strength of the economy, the Fed will be patient in waiting for signs of such a gradual convergence of wage growth towards inflation expectations-consistent rates. I continue to expect no rate cuts before mid-2024.