Oct Personal Income & Outlays: Still Going Strong

Personal wage income and underlying real spending growth rates continue to be strong. Underlying inflation trends eased but remain at elevated levels.

The October Personal Income and Outlays report provides some valuable insights on the U.S. consumer as well as inflationary pressures going forward. This note sketches out some of these insights.

Key takeaways:

Personal income growth out of wages and salaries accelerated in October and runs at a pace that can sustain at least a 3% PCE inflation rate for the year ahead.

The stock of excess savings has NOT run out and continues to be a tailwind for consumption. Between September and October, it fell around $42 billion and equaled about $676 billion in October.

Real PCE growth continues to show a strong momentum, with the underlying (trimmed mean) growth rate outpacing the headline number since April. This suggests that consumption will remain relatively strong in Q4.

Core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the Fed’s favorite gauge of underlying inflation, remains at elevated levels but it showed some downward momentum. However, temporary factors related to recent asset prices movements might have had an outsized effect on this inflation easing.

Wage Income Growth Accelerated.

A dominant source of household income is personal income out of wages and salaries. Today’s report showed some revisions in the recent growth of household income out of wages and salaries since the summer.

Compared to the vintage from last month’s report, the pace of year/year income growth out of wages and salaries for May-September was revised down somewhat (chart above). However, for the first time since June the year/year growth rate accelerated in October, to 5.4% from 4.9% in September.

Last week (November 24th) we got the final revision of the November inflation expectations from University of Michigan Consumer Survey, and this week (November 28th) the year-ahead expectations from the Conference Board Consumer Confidence survey were published. Given these updates, firms’ and households’ year-ahead inflation expectations for November now stand at around 3.5% in PCE year-on-year inflation terms, compared to the 3.2% rate for July-October (chart above).

To interpret wage income growth vs. elevated inflation expectations, I earlier proposed to compare wage income growth with a neutral benchmark growth rate based on trend non-farm business sector (NFB) output growth and either the abovementioned common inflation expectations factor or the 2% Fed inflation target. Similar to what I did when discussing wages and inflation expectations in my October update, I now also incorporate trend labor share growth into this neutral benchmark.

Any deviation in actual household wage income growth above or below the aforementioned neutral benchmark means wage income growth outpaces or cannot sustain in the medium term either survey-based year-head inflation expectations or the inflation target.

The chart above shows that with accelerating personal wage income growth in September, the wage income growth gap based on the “Main Street” year-ahead inflation expectations discussed earlier became zero again. Meanwhile the smoothed three-month moving average was just a notch below zero (light and dark blue lines).

Momentum in the wage income growth gap based on the Fed’s inflation target ticked up to about +1 percentage point, and the three-month averaged version shows a similar gap (light and dark orange lines in the chart above). Across all gap measures nominal wage income growth runs at a pace that certainly can sustain 3% year-head expectations for PCE inflation over the medium term, and thus remains too high to be able to bring inflation back to target.

With household income growth out of wages and salaries running in line with elevated inflation expectations this might be a sign that for now households’ incomes are likely to remain strong enough to keep spending running at a solid pace going forward.

Still Strong Spending Supported by Excess Savings

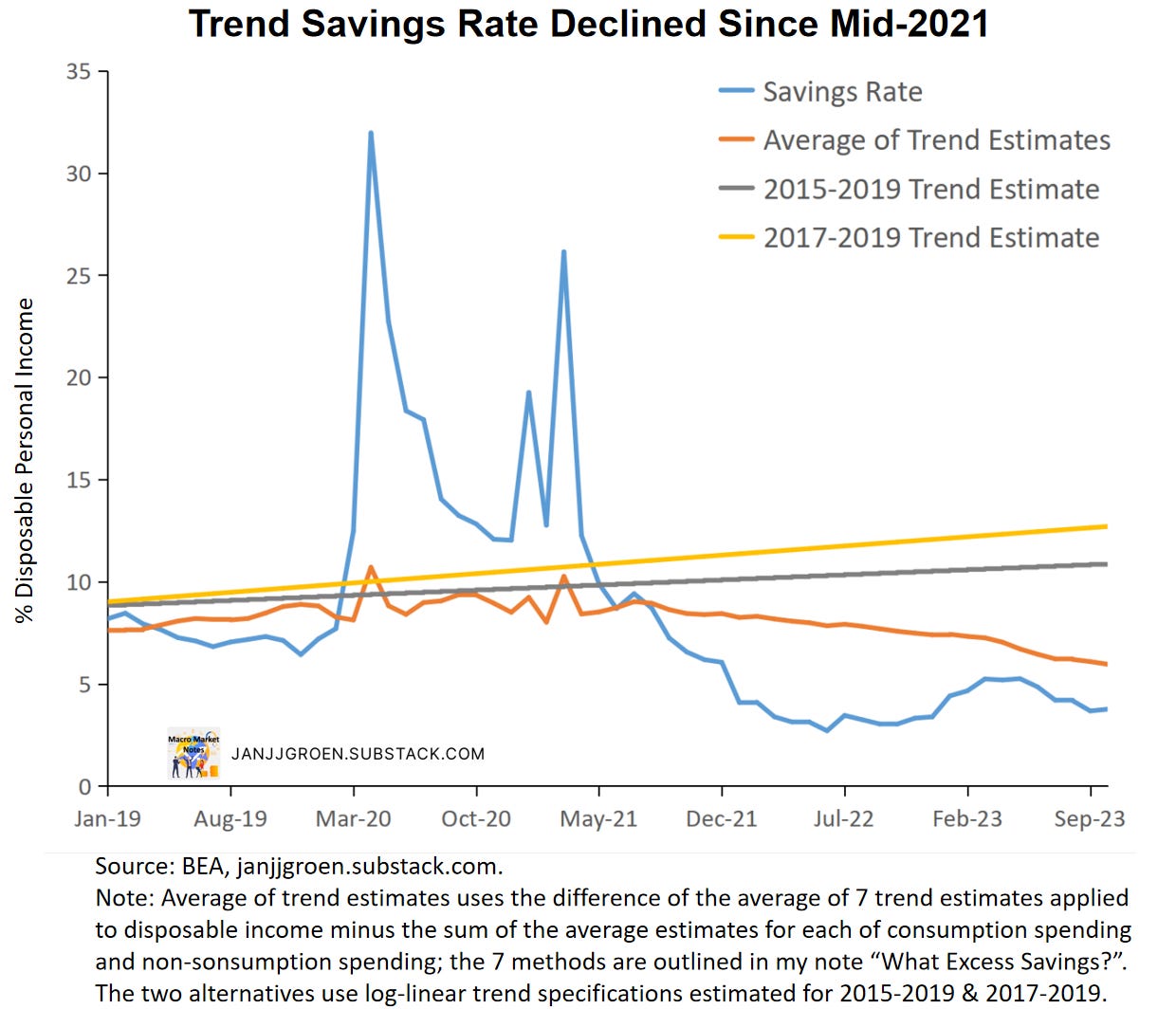

Household spending was up 0.2% over the month in October, a somewhat slower pace compared to disposable household income growth of 0.3% for the same period. As a consequence, the savings rate ticked up from 3.7% in September (revised up from 3.4%) to 3.8% in October.

Despite this increase in the savings rate, the chart above shows that it remains below my trend savings rate estimate of about 6% (down from an upwardly revised 6.1% in September) using the ‘average of trend’ approach outlined in my earlier excess savings note (orange line). The actual savings rate had been diverging to the downside relative to this trend savings rate estimate since May. So, what does this mean for the elusive excess savings of households?

Given the earlier discussed revisions to both personal wage income growth and my estimate of the trend savings rate, in October cumulative excess savings declined from $676 billion in the previous month to about $634 billion (see chart above). Note also the positive contribution of interest payments to cumulative excess savings. This has been declining over the past few months, but despite rising interest rates households’ interest payments1 continue to increase at a below-trend pace.

Squinting at the chart above one observes that during the June-October period the pace of excess savings drawdowns accelerated somewhat compared to the January-May period, likely reflecting the above mentioned downwardly revised pace of wage income growth. Nonetheless, the pace of drawdowns remains below the 2022 pace. Compared to 2022 we continue to see in 2023 that above-trend growth in disposable income, driven by strong wage income growth, partially offsets the drawdowns in excess savings coming from above-trend growth in consumption spending.

Solid Underlying Pace in Consumption Spending

The solid pace of income growth out of wages in 2023 has allowed households to keep up an equally solid pace of inflation-adjusted spending without the need to completely run down the stock of excess savings. With wage growth slowing but still remaining strong at above inflation target pace, this could mean that real consumption expenditures can be expected to remain relatively high for the near term.

As is the case with headline inflation, headline real consumption spending growth often is driven by volatile components that not always reflect the underlying strength of the economy. A core real PCE spending growth measure, therefore, would be really useful, and last month I did that by approximating such a core measure based on constructing a weighted trimmed mean across 177 components2 of headline real personal consumption expenditures.

The chart above shows the resulting trimmed mean real PCE six-month growth rate. The chart makes clear that the trimmed mean measure provides a more accurate reading on the underlying strength of the economy than headline real PCE growth rates, with the trimmed mean measure dipping below headline growth before the onset of a recession.

Focusing on the recent period, the chart above shows the six-month annualized trimmed mean real PCE growth rate in comparison to the headline real PCE. The strength of real consumption in 2022 was basically in line with the underlying growth rate, whereas in 2023 trimmed mean real PCE growth outpaced headline growth.

Underlying consumption growth in 2023 thus far suggests that the economy is far removed from the onset of a recession and in fact shifted to a stronger footing this year. The continued strong pace of trimmed mean real PCE growth likely means that consumption will remain relatively strong in the final quarter.

Tentative Easing of Underlying Inflationary Pressures

In terms of inflation, core PCE inflation decelerated over the month, solely on account of core services inflation. When we focus one of the Fed’s favorite gauges of underlying inflation, core services excl. housing PCE inflation, it remains high compared to the pre-pandemic years. But the gain in momentum observed in the previous month reverted in October in a tentative sign that core services excl. housing PCE inflation might finally start to break free from the post-pandemic 4% trend.

Note, however, that within core services excl. housing core PCE inflation, in particular financial services were especially weak. The PCE price index for financial services declined an annualized 10.1% over the month after gaining 5.8% in September. A main driver of this financial service price weakness were portfolio management fees: the PCE price index for portfolio management fees contracted at an annualized rate of 34.2% in October and fell 8.6% in September. The construction of the PCE price index for portfolio management fees relies heavily on asset prices, and for the October and September the S&P500 declined as well by, respectively, 32% and 12.2%.

So, while especially portfolio management fees have a relatively smaller weight in core services excl. housing PCE inflation, the outsized move in this component in October (compared to its average annualized monthly growth rate of +0.93% in 2022-2023) might have been an extraordinary driver behind the easing seen in core services excl. housing PCE inflation in October. In this context, it is also notable that in November the S&P500 jumped up by an annualized rate of 66.5%. All else equal, this suggests a potential upside risk to the core services excl. housing PCE print for November stemming from a rebound in asset prices in November, especially given the above discussion of trends in wage incomes and spending.

With households’ wage income growth supportive of above-target PCE inflation over the medium term, still sizeable stocks of excess savings, and broad-based underlying strength in real consumption spending, conditions continue to be in place for core services inflation to remain sticky around above-target trends. The downward momentum in core services excl. housing PCE inflation in October, however, is an encouraging sign for the Fed. But it is unclear how much of this downward momentum persists in upcoming data prints given transitory moves in components of this inflation rate, as I discussed earlier. Given these developments it therefore is prudent for the Fed to remain in a “wait and see” mode going forward, while retaining its current restrictive policy stance.

Thanks for reading Macro Market Notes! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Interest payments in the Personal Income & Outlays Report exclude mortgage interest payments.

See Appendix A in the Dallas Fed trimmed mean PCE inflation working paper.